Absent Friends

In which Norm revisits LIVING and AFTERSUN now that they're on disc, and finds plenty to celebrate.

I was going to call this one “Father Figures”, but it felt too on-the-nose, somehow. Anyway, if you’ve read my review of Aftersun you’ll know why the phrase suggested itself … and if you haven’t, well, here you go. Carry on.

I promised reviews of two more TIFF films this week, and dammit, I keep my promises. Let’s start with Living, Oliver Hermanus’ remake of Ikiru, one of Akira Kurosawa’s best and most beloved films.

Remaking Kurosawa might seem like a risky proposition, but it’s paid off in the past: Seven Samurai begat The Magnificent Seven and Battle Beyond the Stars, among others, while Yojimbo was transmogrified into A Fistful of Dollars and Last Man Standing. But those are genre films, and Ikiru is a straight drama – one very much rooted in the context and culture of post-war Japan. There had been rumblings of a remake for decades; I remember Tom Hanks being attached to one a while back, with Steven Spielberg as a possible director. I don’t know that it would have worked, because it would have had to be an American story, and there’s nothing about Ikiru – a film about hope and sacrifice, yes, but also about having the humility and dignity to accept one’s place in society – that feels American to me.

The genius of Hermanus’ remake, scripted by the magnificent Kazuo Ishiguro, is that it refuses to update the story, simply picking up and moving the narrative from post-war Tokyo to post-war London – which of course changes everything about it, because Japan was still living with the shock and humiliation of losing WWII while London’s recovery was that of a hard-won victory. The bones are the same, but the skin is completely different.

Like Takashi Shimura’s Kanji Watanabe, Bill Nighy’s Mr Williams is an undistinguished bureaucratic functionary whose rote existence of politely declining public-works improvements is disrupted only slightly by a terminal diagnosis of cancer. He’s already so withdrawn from his own life that he can’t even bring himself to trouble anyone with the news of his condition, and so Mr Williams simply recedes that much further from his colleagues and his family, taking his existential crisis to the seaside and – despite a night out with a fairly sympathetic fellow – finding no solace there either. But then by chance he bumps into a young woman named Margaret, who recently left public service in search of a more fulfilling career, and her optimism and humanity strike a chord in Mr Williams he’d forgotten how to play.

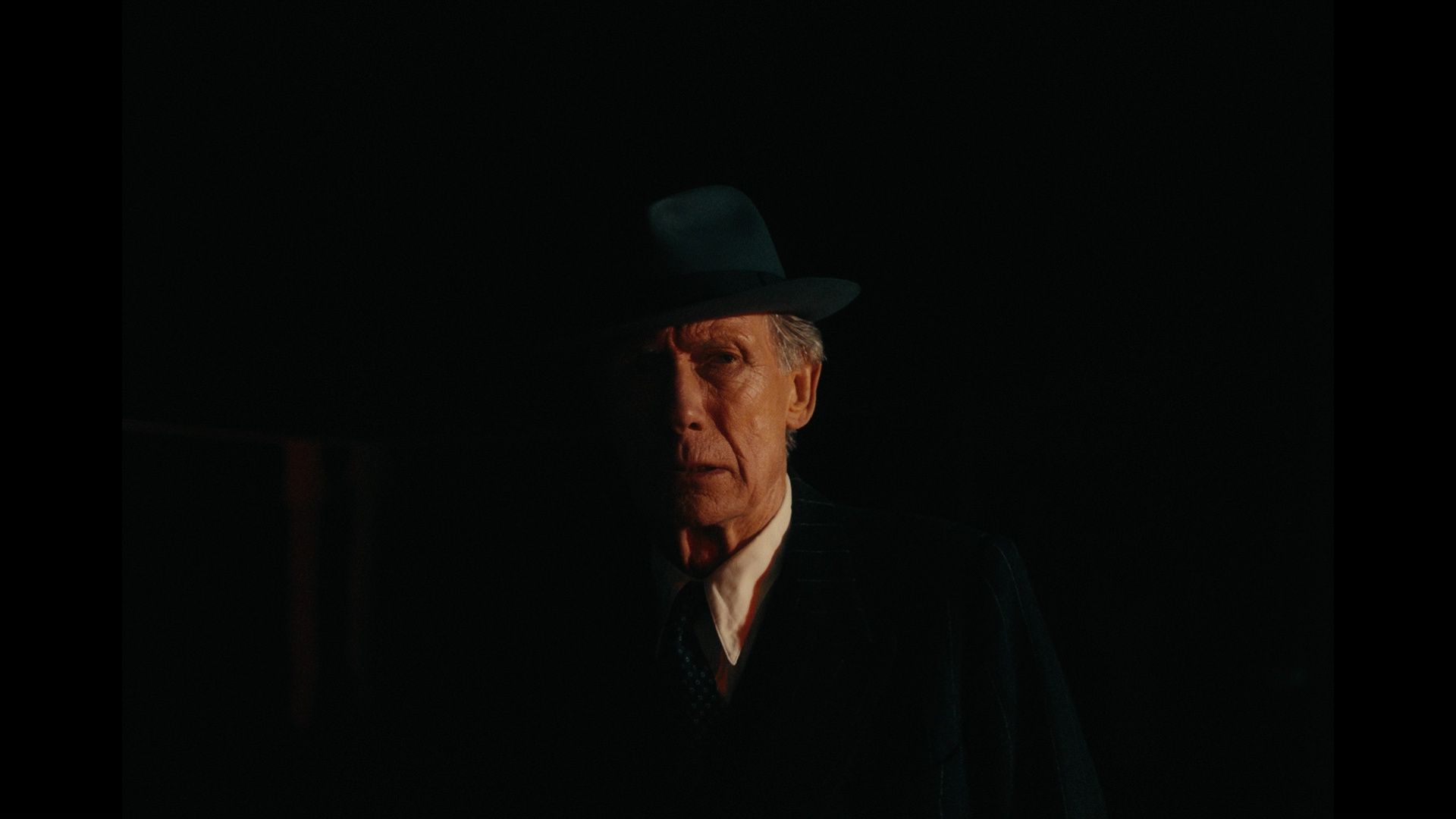

All of this happens in Kurosawa’s film as well – though of course Margaret is Toyo there, played by Miki Odagiri – but again, the transposition to London alters the story’s chemical makeup, as does the casting of Nighy. In the right light, and in the appropriate costume, he looks like a quintessential English stick in the mud – think of the way Edgar Wright uses him in the Cornetto trilogy – but there’s always a flicker of antic energy to signal he’s just having us on. In Living he extinguishes his immense charisma entirely, and without any apparent effort; he simply becomes Mr Williams, a ghost in his own life long before his actual death, and lets us watch this repressed man make a Herculean effort to acknowledge his humanity and put it to some use. In that way Mr Williams becomes a metaphor for England after the war, reawakening to life after a decade of keeping calm and carrying on; in another way, there’s no metaphor whatsoever because this is a movie about this one very specific person doing one very specific thing. It’s right there in the title.

Nighy’s work is exceptional here – I was shocked to realize he’d never been nominated for Best Actor before, but then maybe they never thought he was acting before. And Wood, whom you may know from Sex Education or a pre-pandemic West End production of Uncle Vanya with Toby Jones and Richard Armitage, delicately pushes against the film’s period restraint in exactly the right way, with a warmth and tenderness that shows us why Mr Williams would find himself drawn to her – and why she’d welcome his friendship, once the appropriate parameters are established. Their negotiation of those parameters is a lovely little moment, and a handy reminder that Ishiguro, who wrote The Remains of the Day, is without equal in his understanding of the ways English propriety exists to stifle empathy, keeping people from ever connecting to one another in the name of getting on.

The rest of the cast is equally well-chosen, with faces you’ll recognize if not necessarily be able to place: There’s Alex Sharp as Mr Williams’ sort-of apprentice, and Oliver Chris as another colleague; of the various men in hats and suits, only The Souvenir’s Tom Burke really stands out as that sympathetic fellow I mentioned earlier – intentionally so, I suspect.

Hermanus makes some key aesthetic choices and then lets his actors get on with it, shooting the film in the same squarish frame he and DP Jamie D. Ramsay employed for their last collaboration, Moffie; their choices here are a little more stark, with a bottom-weighted frame that suggests Living was intended to be shown in IMAX venues rather than art houses. And honestly, that’d be fine with me.

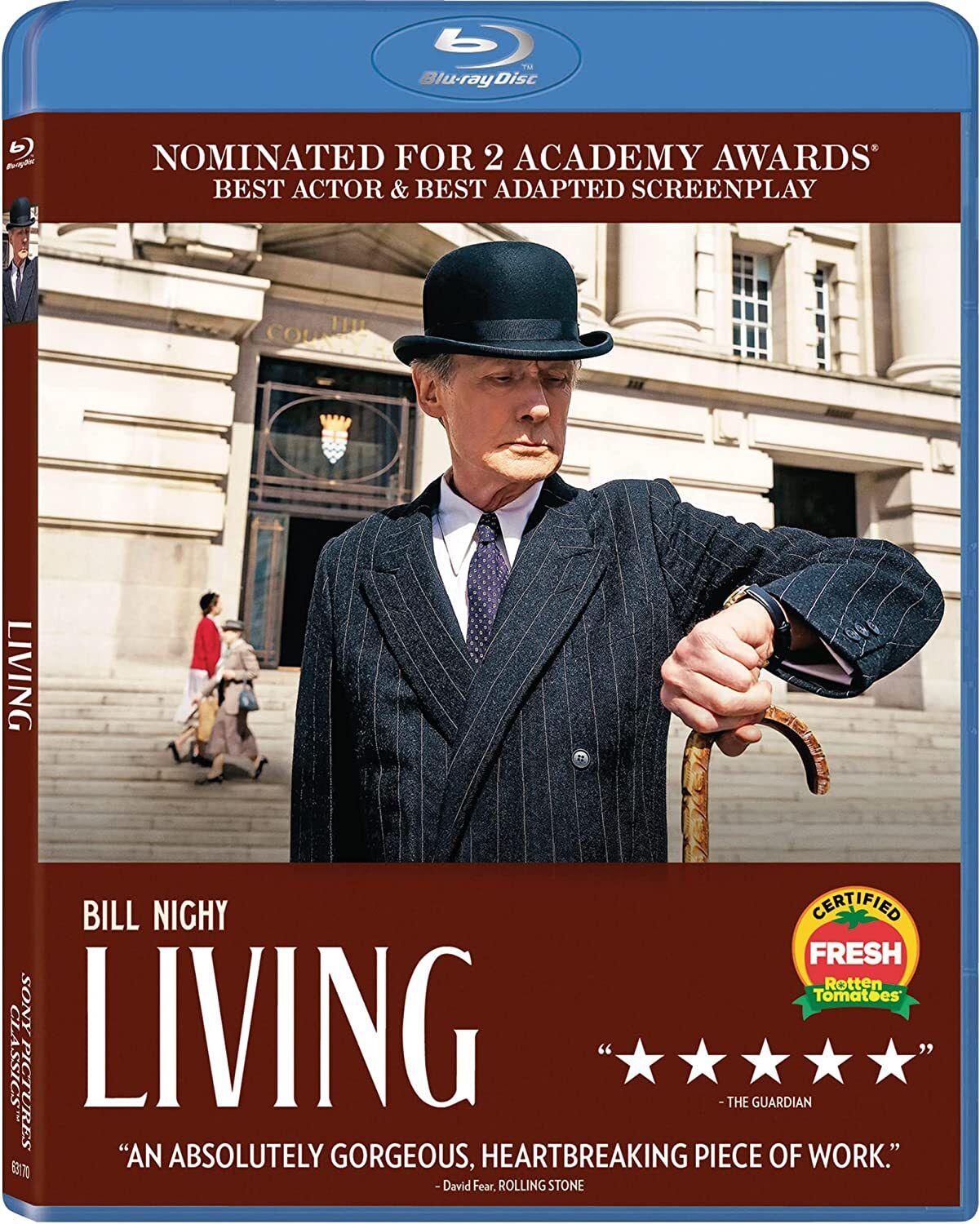

Sony’s Blu-ray of Living offers a pristine presentation of the feature, though it comes up a little short on supplements – just a mechanical production featurette and the theatrical trailer. I can offer you a far more entertaining bonus feature, though: The intro and Q&A from the film’s TIFF premiere last fall, which I was lucky enough to moderate and which became one of the most joyful experiences of my career. Seriously, if anyone ever offers you the chance to spend twenty minutes sitting next to Bill Nighy as he works a crowd, take it. Aimee Lou was an absolute joy, too; she’s currently playing Sally Bowles in Cabaret, and I'd be willing to walk to London for that.

Living came out on disc last month but didn’t reach me until last week – stupid supply chain – but as long as I’m playing catch-up, A24 was kind enough to send me a copy of their bespoke Blu-ray of Aftersun, which also came out in April.

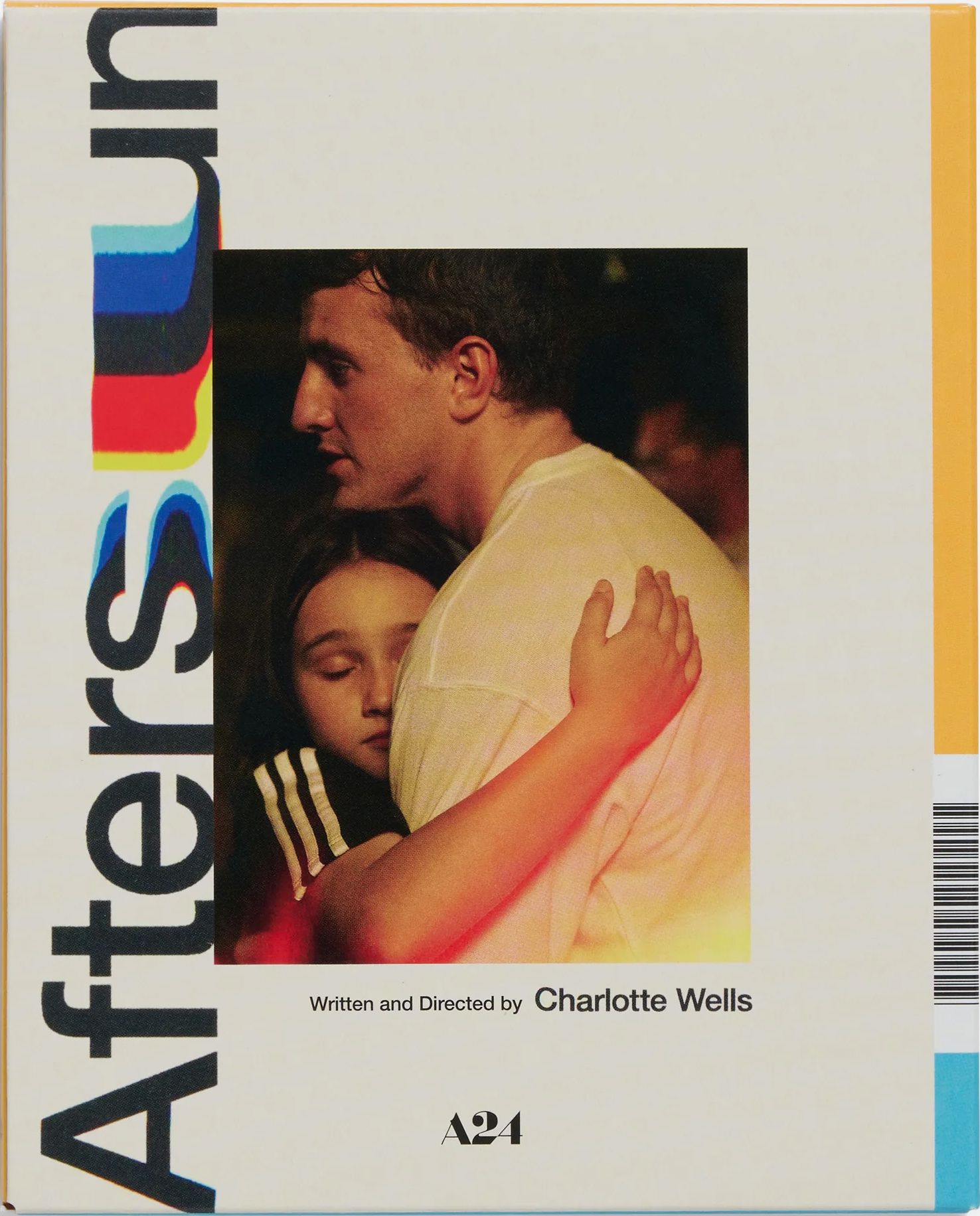

It’s a similarly modest release – the sole supplement is an excellent audio commentary from director Charlotte Wells – but as with everything A24 puts out, the package is as much an art piece as the film it contains, unfolding like a Polaroid camera to disgorge a selection of production photos. The jacket art works in the same vein: See?

The feature is perfectly transferred, in a high-bitrate 1080p master that made me long for a 4K edition, just to see the contrast between Sophie’s standard-def camcorder footage and the bleached daytime and rich nightscapes of the “real” movie – let alone the strobes in the nightclub interstitials – in HDR.

Whoever puts one out is getting my money in a heartbeat; I might still pick up the UK Blu at some point, which further supplements the feature with a deleted scene, a Q&A with Wells, Paul Mescal and Frankie Corio, some behind-the-scenes footage from the London premiere and Wells’ 2015 short film, Tuesday, which now plays as a proof-of-concept for Aftersun.

A24’s website lists the disc as sold out, but a second pressing seems inevitable … and I understand at least one Toronto retailer managed to import a few copies for brick-and-mortar sales. Us physical media folk have to stick together. And yes, if you were wondering, the film holds up: It’s beautifully realized, achingly specific and heart-crushingly sad. Let it in, it’s good for you.

In Sunday’s paid edition, I let my inner child play with Warner’s 4K set of the Superman movies. You might want to bump your subscription up a tier for that.