Creatures, Featured

In which Norm finds himself surrounded by monster movies. Which, as it turns out, is his happy place.

I love monster movies. Always have. Big or small, rampaging or methodical, I’ll always turn up to see how a filmmaker handles their chosen beast – and how the human characters deal with it. If we’re very lucky, we’ll get something brand new … though most of the time the result is all too familiar. This week is positively awash in monsters, and every sort of approach is represented.

Consider Wolf Man, Universal’s latest reinterpretation of a classic property from writer-director Leigh Whannell, who delivered a genuinely revolutionary take on The Invisible Man five years ago. This one also offers a contemporary update of a beloved black-and-white creeper … but rather misses the mark, burdening the tale of an innocent man cursed to become a rampaging beast when the full moon rises with a lot of distracting, ultimately unnecessary baggage.

Whannell’s version casts Christopher Abbott as Blake Lovell, a writer scarred by a rough upbringing in the wilds of Oregon at the hands of his overprotective father Grady (Sam Jaeger). Blake moved away at the first opportunity, and now lives in San Francisco with journalist Charlotte (Julia Garner) and their young daughter Ginger (Matilda Firth), trying to be a better father – and, we can assume, a better husband – than Grady ever was. And when the time comes to settle his father’s estate and clean out his house, a summer back home seems like a nice way for Blake and his busy family to reconnect with one another.

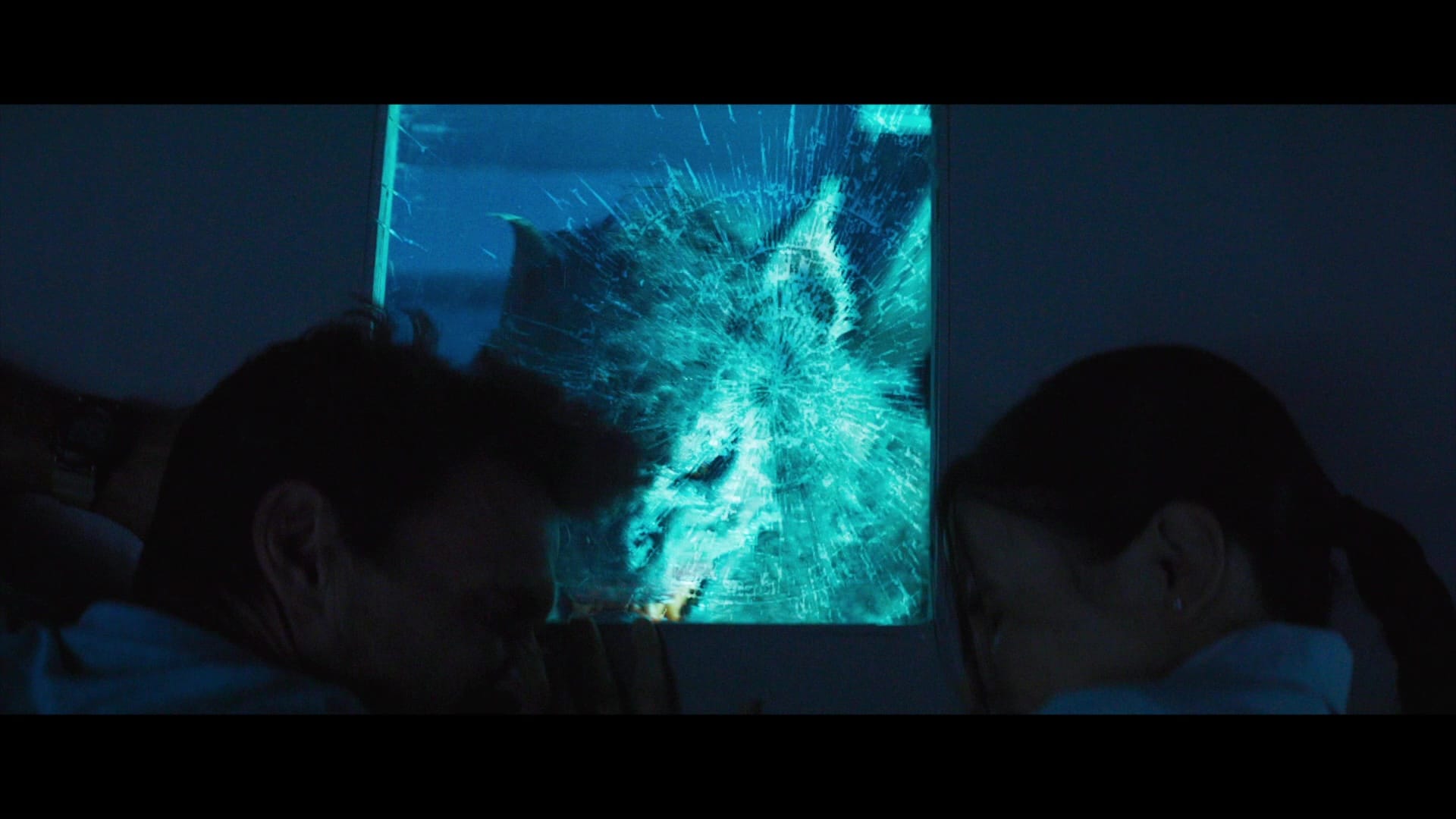

Of course, this being a movie called Wolf Man, a pleasant vacation is not in the cards. No sooner have the Lovells found the right road than something attacks their truck, killing their guide and leaving Blake with a badly wounded arm. The family makes it to Grady’s house, but the creature is close on their heels … and now Blake is exhibiting signs of incipient monsterism. Which is great for fans of icky body-horror effects, but not exactly setting the stage for a pulse-pounding thriller.

Or maybe it could have, if Whannell had leaned into the urgency of a family facing external and internal threats to power his story. Instead, he positions Wolf Man as a very serious examination of sickness and loss, giving characters early monologues about the essential fear all parents have of not being able to protect their children, the fragility of relationships and how death comes for us all.

It’s not impossible to make a horror movie about these very things – David Cronenberg made The Fly after losing his father to cancer, and the tragedy of that film isn’t the transformation of Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle but the way it snuffs out his newfound romance with Geena Davis’ Veronica. But by restricting the main narrative to a single night and deciding that werewolfism is a one-way trip, Whannell hobbles himself: Abbott sits around passively for most of the film, losing teeth and sprouting hair as the prosthetics take over, while Garner looks worried and occasionally fends off the beast outside.

Worse, Whannell doesn’t explore any of the questions he’s raised: Becoming a monster doesn’t unleash anything in Blake, since we’re shown the infection is literally overwriting him – his mind is changing along with his body, degrading his ability to communicate with or even recognize his family. And while his father’s behavior decades earlier implies deeper knowledge of whatever’s in the forest (the film even opens with some lore about a malady known as “hills fever,” which the Indigenous people called “the face of the wolf”), that never amounts to anything either.

As Whannell mentions in this excellent interview with Film Freak Central’s Walter Chaw, everyone has such specific ideas about werewolf mythology that any variation was going to be met with skepticism. But I’d argue that changing everything was a terrible idea on its face; Wolf Man is so intent on elevating its concept that it seems ashamed of the original material, to the point that Blake’s ultimate beast form looks more like Gollum than anything canine.

Contrast this with Steven C. Miller’s Werewolves, which arrived a month earlier – hey, free advertising is free advertising – and immediately sets out to give its audience exactly what they want: Big honking werewolves rampaging through the night, hunting terrified humans and occasionally smacking each other around. To cite another Universal franchise, it’s The Purge, but with werewolves. They even got Frank Grillo for additional Purge cred!

Matthew Kennedy’s screenplay goes straight for the silliness: One year ago, we’re told, a supermoon unleashed the beast in everyone whose light it touched. A billion people died, and now that the world has barely recovered, the phenomenon is about to repeat itself. With humanity locking down time zone by time zone, a team of scientists – led by Grillo, NCIS star Katrina Law and Lou Diamond Phillips in a nice suit – is conducting a test of a nanoparticle spray that can block the supermoon’s effects, offering hope for the future.

But faster than you can say “What’s the title of this movie again?”, things go sideways and our heroes are running for their lives through a city crawling with seven-foot ravenous monsters, armed only with their wits, a dwindling supply of not-entirely-effective moonblock and some very big automatic weapons. Which is all we wanted in the first place.

I can’t argue for Werewolves as a good movie, exactly. It’s cheerfully boneheaded in its logic, and though it occasionally overreaches in its real-world allegories – like having Grillo’s sister-in-law and niece live next door to a MAGA gun nut, when surely those guys would be lining up to embrace their inner beast – Miller’s been making genre pictures for a couple of decades now, ever since the zombie cheapie Automaton Transfusion, and he knows how these things work.

He loves playing in the monster sandbox and showing off his team’s practical creature work, and he’s good enough with actors that he can just sell the idea of a world still traumatized by the silliest global catastrophe imaginable.

Well, the second silliest. Because Kyle Mooney’s Y2K is also on the shelves this week.

Did you see Mooney’s first big-screen project, Brigsby Bear? Not a lot of people did, but it’s a strangely beautiful comedy about a maladjusted young man trying to come to terms with his abduction as a child by completing the fake television show his captors created to pacify him. In cold type, it’s complicated; in execution, brilliantly simple and utterly heartbreaking. I’d never seen anything quite like it, except maybe Synecdoche, New York, but the two films have nothing in common beyond their heroes’ despairing attempts to make sense of the world by fabricating a different reality.

If you’ve seen him on Saturday Night Live, or caught even one episode of his retro Netflix series Saturday Morning All-Star Hits!, you know Mooney loves weird freaks trying to make their way through a world they don’t fully understand. In his directorial debut, Mooney sticks to what he knows, making his version of an ’80s teens-and-sci-fi picture that somehow looks backward and forward at the same time.

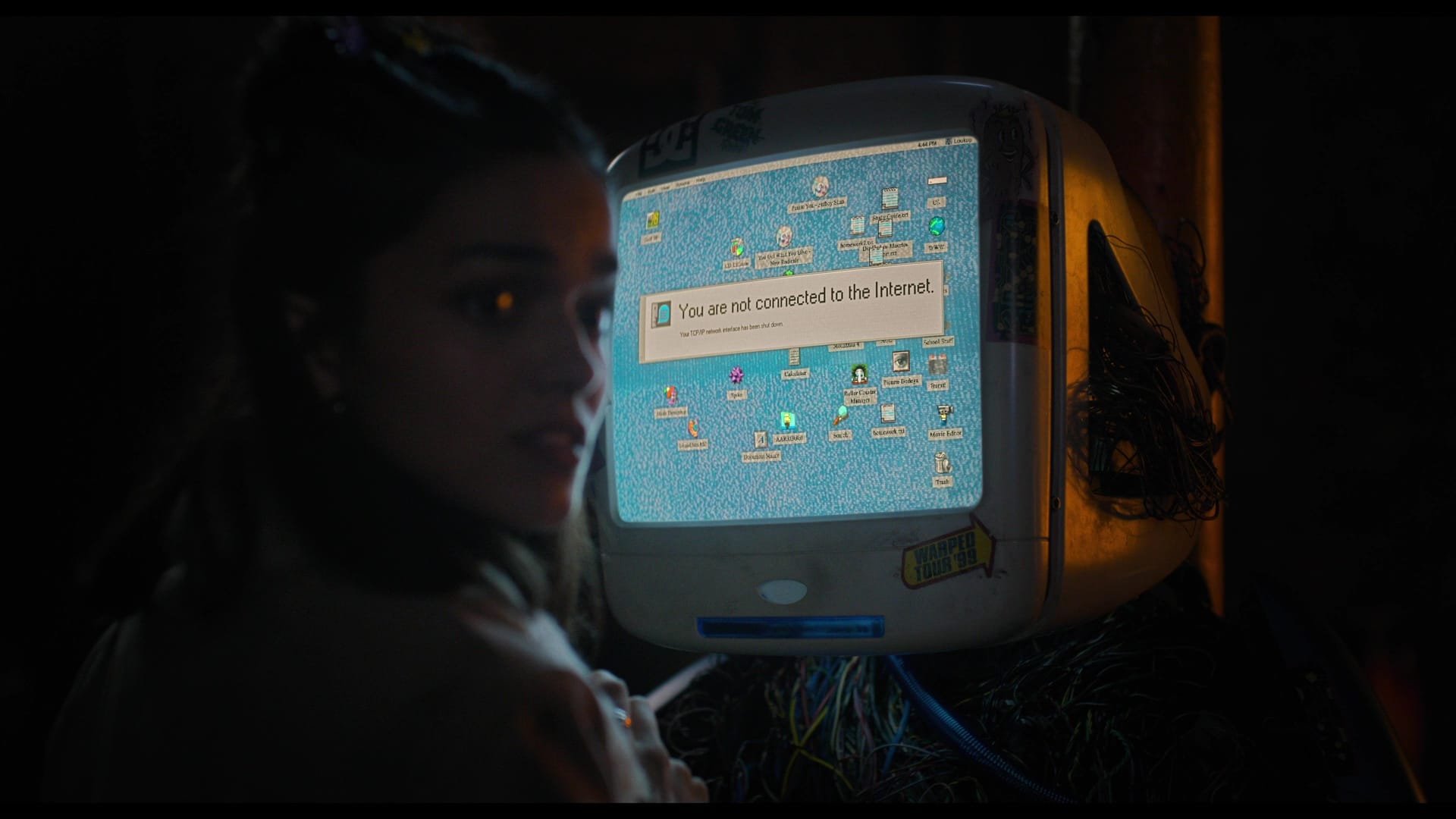

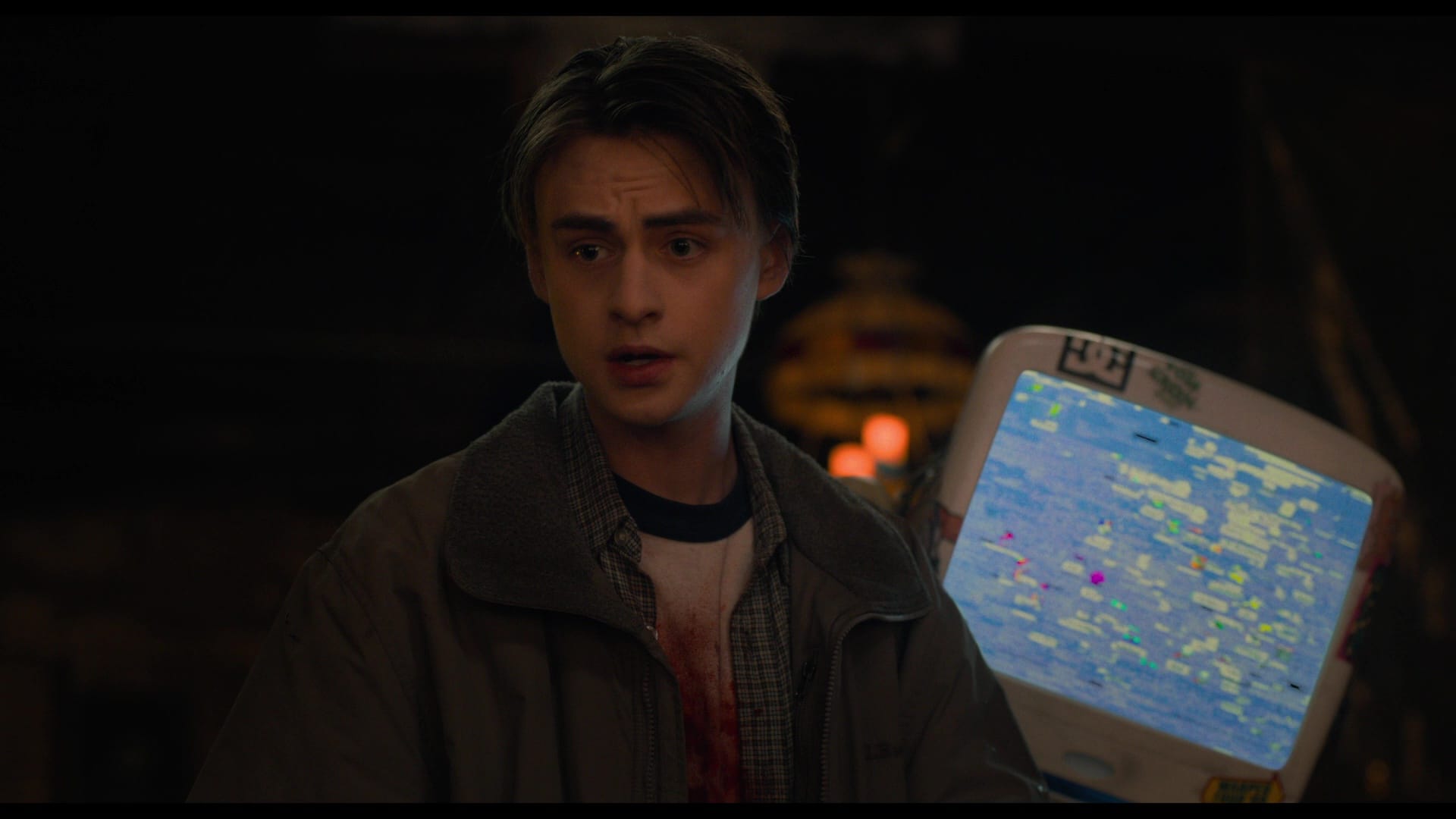

Set in a generic American town on December 31, 1999, Y2K focuses on misfit teens Eli (Jaeden Martell) and Danny (Julian Dennison), who are planning to spend New Year’s Eve playing videogames and sulking. (It’s the same thing they do every night, Pinky.) But when they bump into Eli’s crush Laura (Rachel Zegler) at the quickiemart, they’re invited to celebrate the turn of the millennium at a house party – where, at the stroke of midnight, every machine in the place starts trying to kill them.

The resulting splatter is both distressing and very funny, as our heroes do their best to escape the slaughter and figure out what’s happening and how to fight back: Danny is good at inspirational speeches, Eli is good at ducking, and Laura is a coder who might have some ideas about disabling whatever virus is running rampant through the town’s computers. (The attention to detail is truly impressive, from recreations of WinAmp and Windows 98 to the image quality of the various camcorders that are picked up and abandoned over the course of the story.)

More importantly, Y2K understands the emotional tone for its preposterous narrative: Mooney knows that the confusion of adolescence lines up perfectly with the panic of a disaster film. There’s a scene that references Powers Boothe’s big monologue in Red Dawn, and I’m pretty sure Mooney’s a fan of Night of the Comet, too. He’s also great with his actors, giving Zegler the kind of star turn she hasn’t really had since West Side Story – she’s got a great monologue about how being popular in high school isn’t something anyone should want – and making sure supporting players like Lachlan Watson, Daniel Zolghadri and Mason Gooding get to pop amidst the chaos. And even though Martell’s Eli is more straight man than hero, he has his moments too. Even when he's trying to convince his pals to spare his newly-anthropomorphic PC.

… okay, so maybe Werewolves is the week’s third silliest release, because Renny Harlin’s Deep Blue Sea is also in the house.

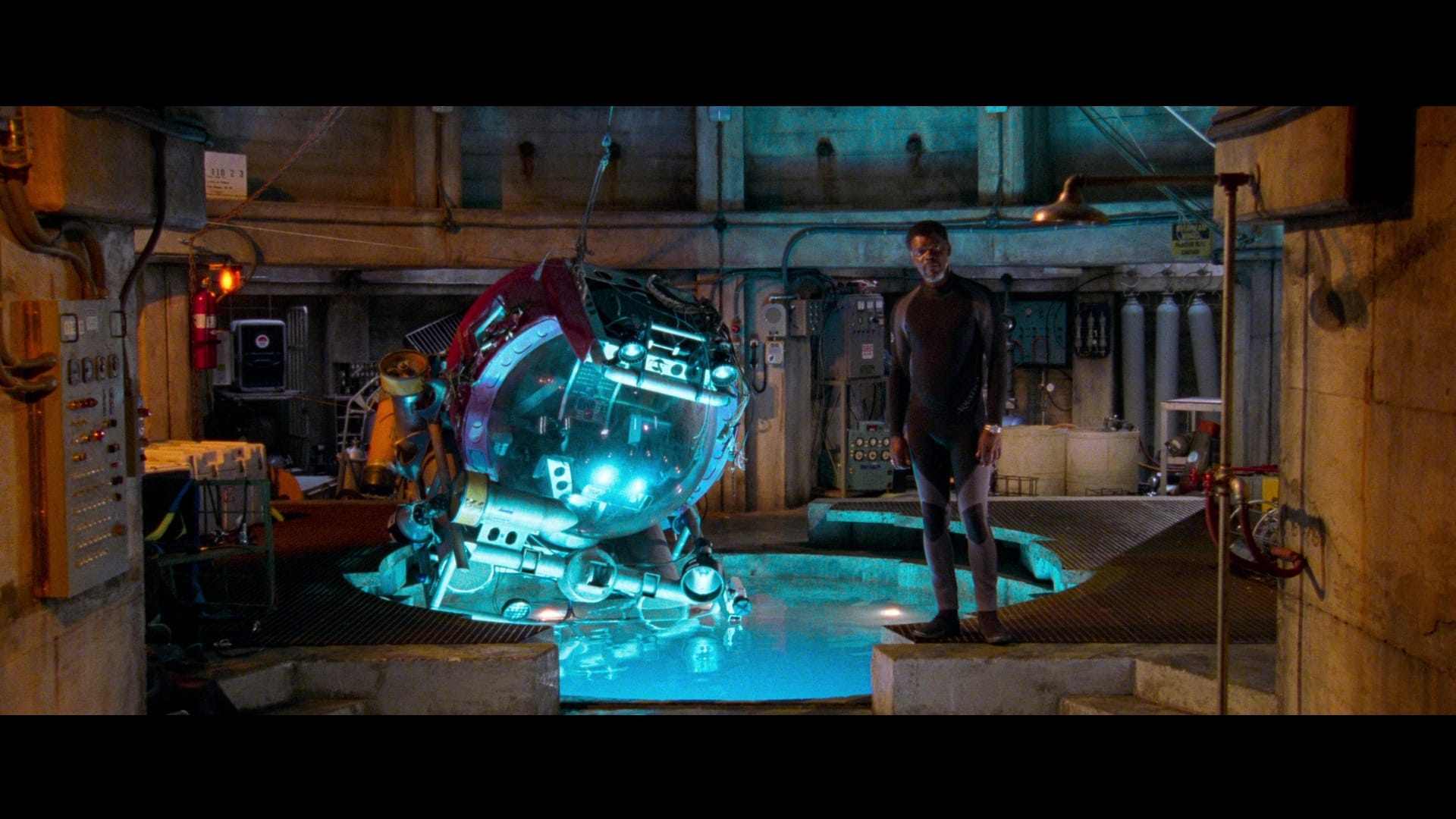

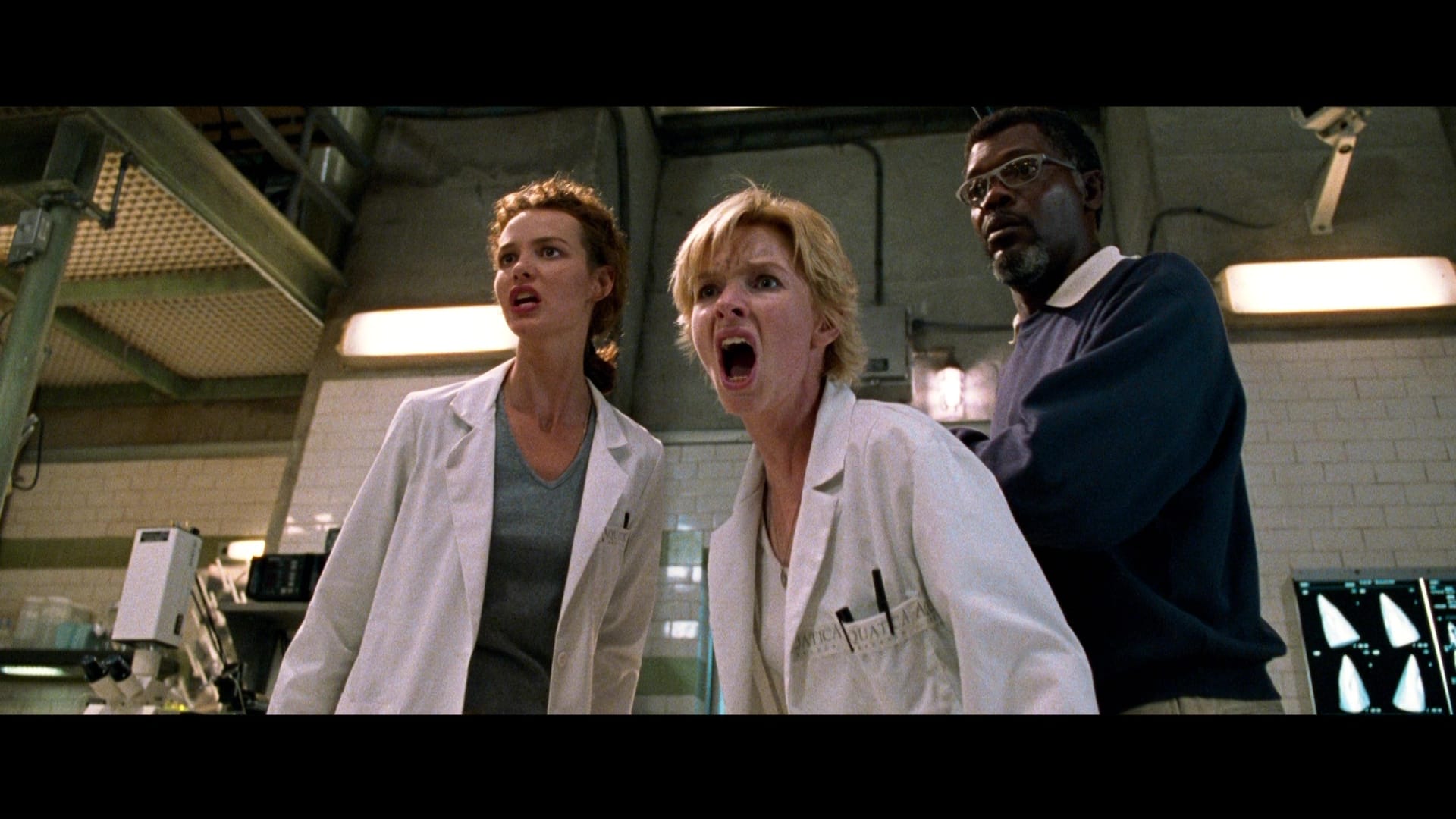

You remember this one, right? It’s the one where well-intentioned Alzheimer’s research leads to a group of scientists being hunted in their own underwater facility by their super-sharks, who’ve gotten smart enough to realize they really don’t like having their brains harvested for miracle proteins. It’s got a really eclectic cast – Saffron Burrows, Stellan Skarsgård and Jacqueline McKenzie as scientists, Michael Rapaport and Aida Turturro as facility staff, Thomas Jane as a roughneck shark wrangler, LL Cool J as the station’s chef, and of course Samuel L. Jackson as the corporate backer who gets to take charge during the crisis … and deliver a speech at the one-hour mark that’s become a YouTube staple.

Harlin being Harlin, it’s very polished action picture that either doesn’t know how dopey it is or simply refuses to admit it. The structure is straight out of Jurassic Park, but Harlin also borrows ideas and elements from dozens of other action movies, including a key moment from his own Cliffhanger, for an enthusiastic goulash that cannot help but satisfy. Received with some confusion in the summer of 1999 (when it opened against the actual disaster Mystery Men), it’s been reclaimed over time as a genuine trash classic, and this week Arrow Video gives it the special edition it’s always deserved.

The feature (beautifully restored in 4K, with both its original 5.1 soundtrack and a new Dolby Atmos mix) is accompanied by two new audio commentaries: One from screenwriter Duncan Kennedy, who grouses about the script’s path to the screen, and a more celebratory track from podcaster Rebekah McKendry.

And in addition to the extras produced for Warner’s earlier discs – audio commentary from Harlin and Jackson, two production featurettes and a reel of deleted scenes viewable with or without Harlin’s commentary – Arrow has commissioned a suite of new supplements.

“From the Frying Pan into the Studio Tanks” is a half-hour interview with production designer William Sandell, who in addition to discussing this particular project also shares some very fun stories about his early days hanging out with Jonathan Demme and Martin Scorsese when they all worked for Roger Corman. And in the visual essay “Beneath the Surface: The Monstrous Feminine in Deep Blue Sea,” critic and podcaster Trace Thurman deploys an explicitly Freudian reading of the film and its development to argue that Burrows’ obsessed scientist is the story’s real villain, rather than the sharks. Test audiences certainly thought so … though it’s worth pointing out no one wanted that nice Mr. Hammond to die in Jurassic Park. Weird, huh.

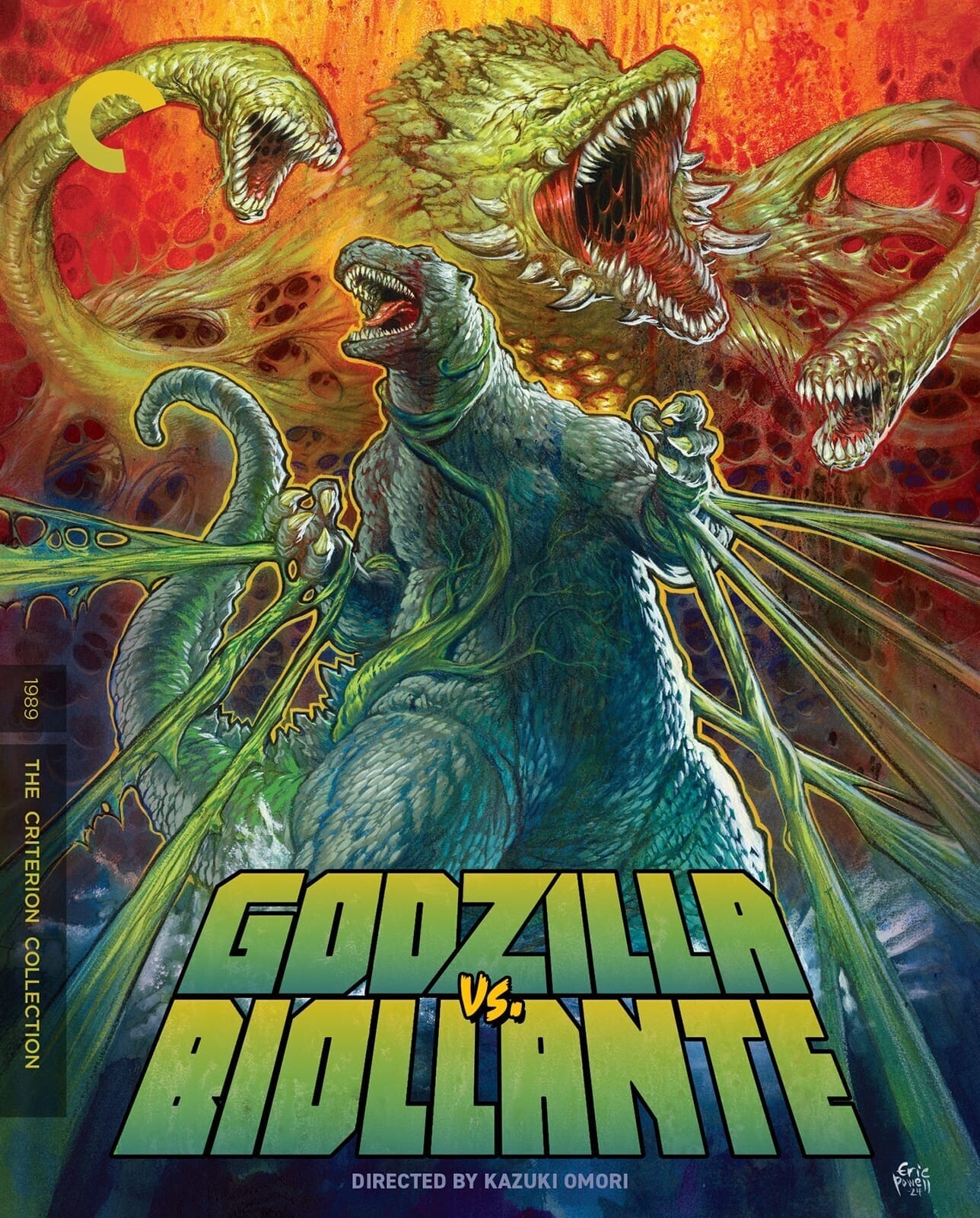

Finally, we come to the main event: Godzilla Vs. Biollante, a monster movie that is not silly at all – though it certainly could have been.

Five years after The Return of Godzilla (aka Godzilla 1985) revived the king of the monsters after a decade’s slumber, Kazuki Ōmori’s ambitious monster movie pitted him against a new kind of opponent – a genetically engineered combination of human DNA, a rose and Godzilla’s own cells, resulting in an almost Lovecraftian beast that ultimately towers over our hero, and threatens all of Japan – and perhaps the world – with extinction.

As the filmmakers explain in the documentary that accompanies the feature, this was the first Godzilla movie made by people who’d grown up with the Showa movies, and saw the character in a way its creators couldn’t. Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka let his effects teams run wild with Biollante, which at the time was the most complex kaiju suit ever attempted, requiring as many as twenty puppeteers. And Ōmori’s script expanded on ideas that had been floating around Toho’s previous kaiju movies, introducing Megumi Odaka as a teenage psychic who would become a sort of monster interpreter over the course of the subsequent cycle, and grounding the story in the misguided grief of Dr. Shiragari (Kōji Takahashi), the scientist who accidentally unleashes Biollante.

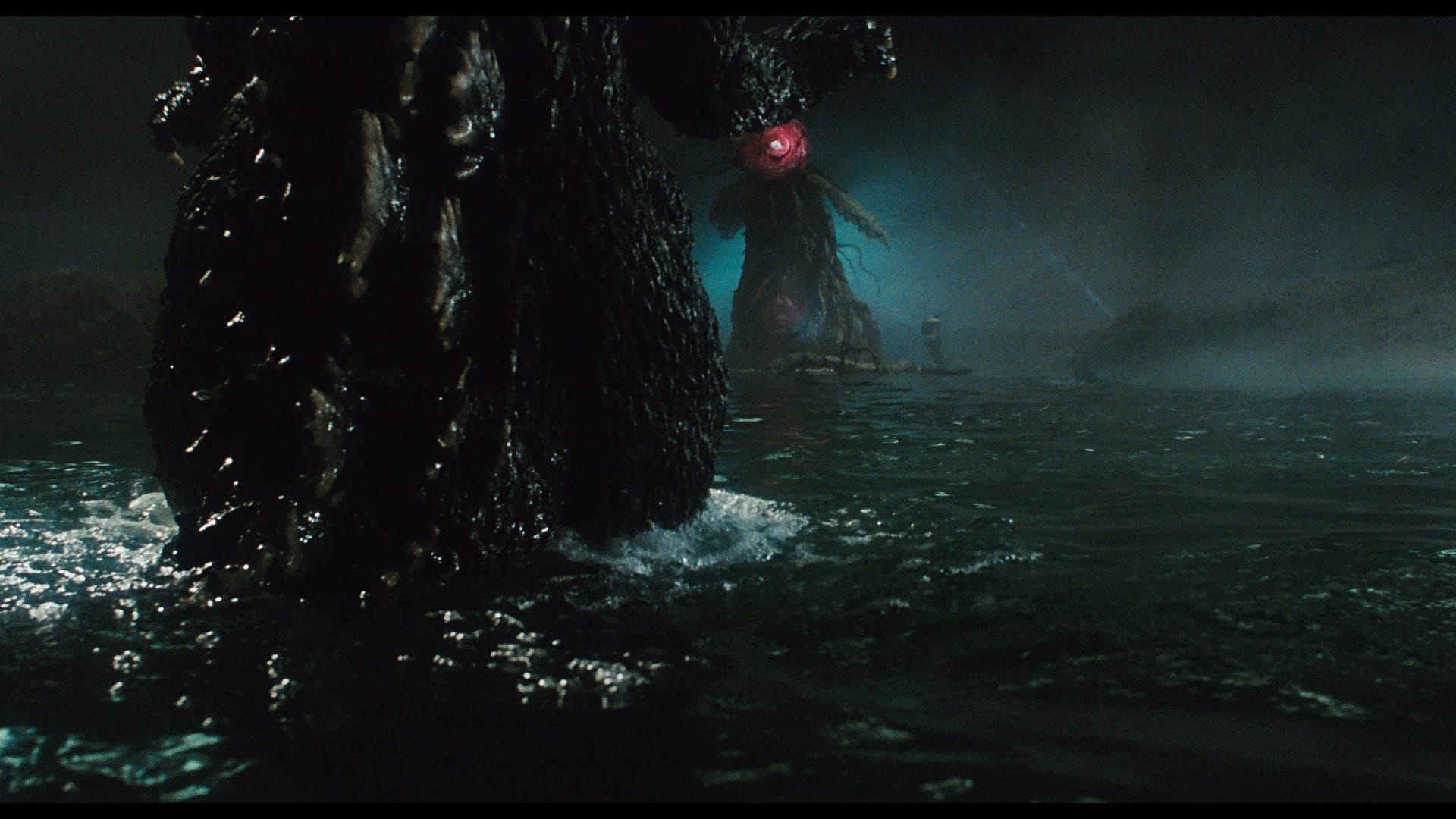

Everything in this movie happens for a reason, and while kids could certainly enjoy the monster-on-monster action, this was the first fully grown-up Godzilla movie since the 1954 original. It’s also just beautiful to look at, especially in the new 4K restoration that lives at the heart of Criterion’s new release.

Other than a new audio commentary from podcaster Samm Deighan, the supplements on the accompanying Blu-ray are all drawn from the archives. That appealingly honest 50-minute documentary produced at Toho in 1993 first appeared on the Japanese DVD, as did the reel of alternate designs for Biollante and the Super X2 flying tank; we’re also treated to longer cuts of the deleted monster scenes glimpsed in the documentary. But the real highlight is the glorious restoration of the film, which looks like it was shot yesterday, its practical monster suits and miniature effects rendered to the smallest detail. And the lighting! The lighting looks incredible in UHD, bringing out the ambitious stylistic choices that kaiju movies hadn’t bothered with in decades.

It’s a massive improvement on the budget Blu-ray released about a decade ago by Echo Bridge, which relied on an older master from the Miramax vaults. It was fine at the time, since it put the movie back into circulation in North America after a long time in limbo, but Criterion’s new master shocks Godzilla Vs. Biollante back to life. The Criterion and Unobstructed View flash sales might still be on when you read this, but if you missed it, this one’s worth the full sticker price.

Wolf Man is now available in 4K/Blu-ray combo and Blu-ray editions from Universal Studios Home Entertainment; Werewolves and Y2K are available on Blu-ray from VVS Films; Deep Blue Sea is available in individual 4K and Blu-ray editions from Arrow Video (and Unobstructed View in Canada) and Godzilla Vs. Biollante is available in 4K/Blu-ray combo and Blu-ray editions from the Criterion Collection (and Unobstructed View in Canada).

Up next: We jump back to 1975 and find Ken Russell and Arthur Penn at their idiosyncratic peaks, and of course paid subscribers get my exclusive What’s Worth Watching alert every Friday; upgrade that subscription and see what you shouldn’t be missing!