Englishmen, Talking

In which Norm reviews the new releases of MY NAME IS ALFRED HITCHCOCK and HERETIC ... which both love a good monologue.

Mark Cousins is, as the kids say, a real one. The man lives and breathes cinema, taking it apart and putting it back together again in one essay project after another: His 15-part history The Story of Film: An Odyssey was just the first salvo, followed by A Story of Children and Film (which we discussed when he brought it to TIFF), Women Make Film: A New Road Journey and The Story of Film: A New Generation, each new chapter expanding on the last, finding new angles and observations and offering audiences a new list of things to seek out and enjoy. He’s an evangelist of the movies, even literally bringing them to remote audiences with his pal Tilda Swinton, and I am always excited to see what’s caught his fancy.

He also has a sideline in what I’d call psychological investigations of specific filmmakers, starting with The Eyes of Orson Welles and The Storms of Jeremy Thomas, and now My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock, which unpacks the motifs and themes of the man who defined suspense cinema as well as anyone – and more than most – through the device of Hitchcock himself revisiting his movies from beyond the grave. Dead forty years, and still offering opinions.

Cousins’ film opens with the cheeky credit “Written and Voiced by Alfred Hitchcock,” which is of course utter bollocks; the absent filmmaker is voiced by Alistair McGowan in all his glottal glory, and Cousins himself supplies the script. But it’s a hoax in good faith, a wink to the audience that the work we’re about to see is an attempt to honor Hitchcock rather than dissect him.

“Hitch” cheerfully takes us on a tour of his filmography, shuffling through his work and expounding on what Cousins believes are the six pillars of his cinema: Escape, Desire, Loneliness, Time, Fulfilment and finally Heights.

Each section offers a stream of juxtapositions and commentary, with McGowan’s voice plummily explaining the ways in which Hitchcock returned to these essential conceits over and over again, frequently with the same actors. (“Grace again,” he notes in the Desire section as Cousins follows a clip from Rear Window with one from To Catch a Thief.)

It’s all designed to bring us to a larger understanding of Hitchcock’s own fascinations and compulsions, with a particular focus on his mordant wit: A clip of Sylvia Sidney slicing meat for the insufferable Oskar Homolka in 1936’s Sabotage is deconstructed to demonstrate the murderous rage building inside her.

Cousins clearly loves Hitchcock’s work, offering a gentler take on the director than others have offered; there’s no sign of Sir Alfred’s famously controlling behavior, or his reported mistreatment of his leading ladies. (This version of Hitchcock has nothing but affection for Tippi Hedren, who remembers their working relationship very differently.) That said, “I’m a genius and everyone loved working with me” is the way Hitchcock himself would remember it, so bear that in mind as you watch the picture.

Cohen Media Group’s Blu-ray offers a solid 1080p/24 presentation of the feature, with the various film clips presented in decent if not eye-popping quality; it doesn’t appear that Cousins had access to the freshest masters of the Hitchcock catalogue. Psycho, Rear Window, Vertigo and Family Plot look terrific, for instance, while The Birds, Rope and Torn Curtain look a little rougher than they do in their 4K releases. (The sharpness and stillness of Cousins’ digitally-shot inserts provides immediate contrast to the more organic qualities of Hitchcock’s photochemical work.) Audio is offered in both 5.1 and 2.0 DTS-MA, though only a handful of moments nudge the soundstage beyond the front speakers.

Extras are modest but illuminating. In a virtual interview, Cousins explains his methodology in an episode of Chuck Rose’s NYC Media series Cinema Q&A, answering all the obvious questions about the project and even showing Rose how to properly hold up his copy of the Hitchcock/Truffaut hardcover.

Other extras include animation tests, audio of McGowan’s voice test for Hitchcock and an alternate trailer with Cousins doing the voice himself far less effectively. The actual trailer is also here, as well as Cousins’ recorded introductions to Notorious, Rope and Saboteur, which screened alongside his documentary at London’s Riverside Studios last August.

Heretic has a lot in common with Rope, come to think of it. The bulk of it takes place in a single location – an unassuming home in an American suburbia – where two young people are drawn into a battle of wits with a cagey older fellow. Writer-directors Scott Beck and Bryan Woods also add dashes of Psycho and Shadow of a Doubt, at least in the first half, before taking the story in a very different direction.

Heretic opens with two young Mormon missionaries glumly making their rounds and wondering whether there’s even a point in offering their gospel to people who just want to mock their faith. Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher) can give as good as she gets, at least, while Sister Paxton (Chloe East) is far less assertive. Sister Barnes wants Sister Paxton to be more like her. We get the sense Sister Paxton might want that, too.

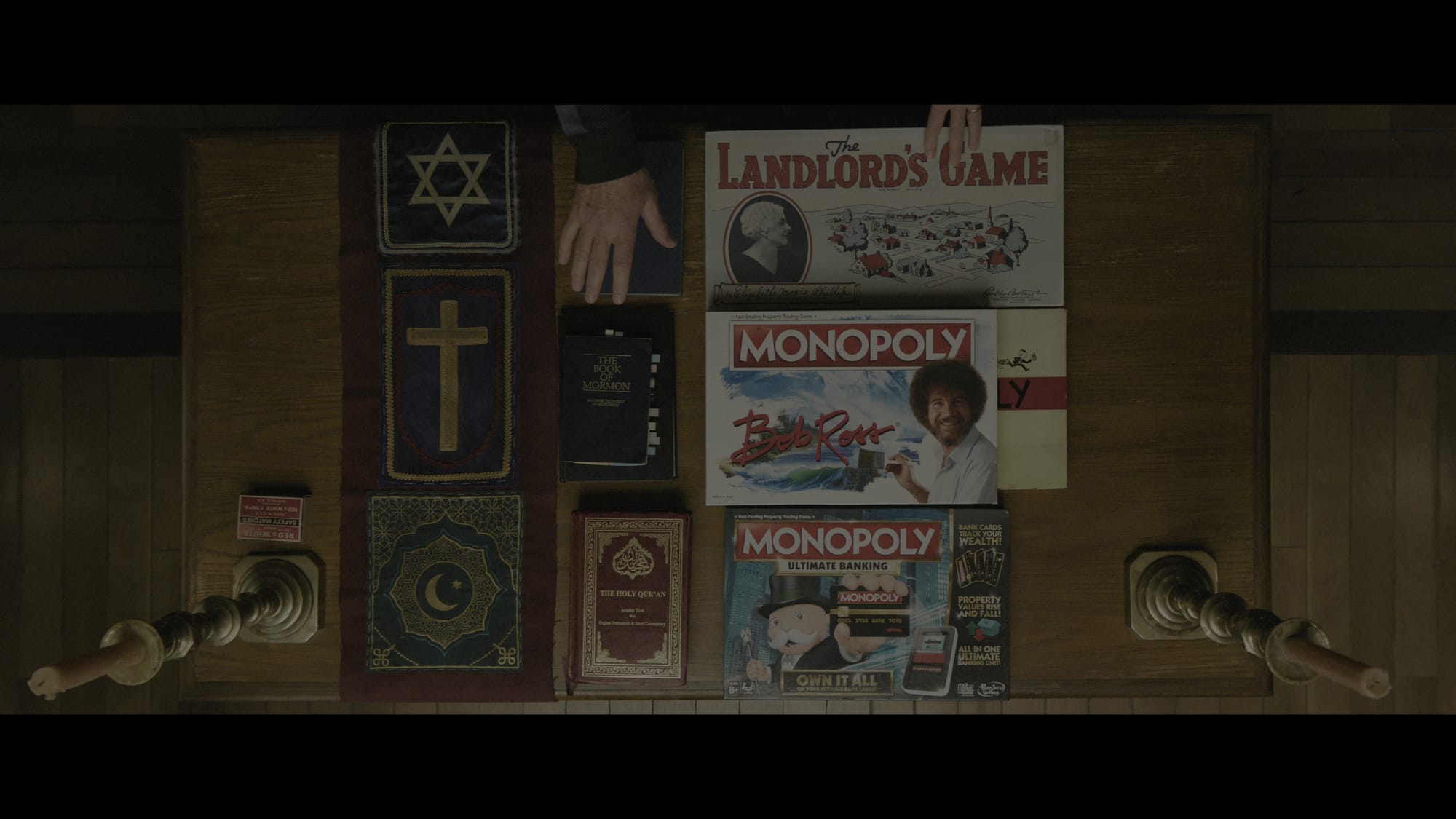

And then the pair find themselves in the home of genial Mr. Reed (Hugh Grant), a genial, chatty sort who tells them his wife is in the kitchen baking a pie that she’d be more than happy to share with them when it’s ready. He has questions about Mormonism, and seems willing to engage the sisters respectfully and with curiosity rather than hostility. He talks. They listen. And gradually they come to understand he won’t let them leave.

I suspect Heretic began as Beck and Woods’ response to A Quiet Place – which they wrote, before John Krasinski added all those exclamation points –becoming a monster hit. That film played out with a handful of spoken lines; Heretic is all dialogue. But in execution it leans heavily on other movies in which characters are trapped together in a pressure-cooker situation – specifically Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs, Ari Aster’s Hereditary and Zach Cregger’s Barbarian – and we know how those go.

You want convoluted theories about iterative ideation, and the way every major religion is built on the framework of the one that came before it? They're here. You want long takes of people staring into darkness, terrified at what they might find? They're here too. You want sudden, decisive acts of violence? Just wait until they get to the creepy cellar! (These houses always have a creepy cellar, don’t they?)

At 90 minutes, and with more of the quicksilver energy that Thatcher brought to projects like Prospect and Yellowjackets, this could have been a tense little thriller. But at nearly two hours, Heretic just gets less and less interesting the more it reveals about its ultimate goals: Beck and Woods want to make a movie criticizing pontificating windbags, but first they have to let their windbag pontificate. And while Grant is initially mesmerizing as a cheerful, seemingly all-knowing monster, the movie asks more of him – and us – in its final act than he can deliver.

It does look good, though, with ace cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon capturing Mr. Reed’s cozy sitting room with a sickly digital sheen – accentuated by the HDR grade on A24’s 4K edition – that makes us tense up the moment the sisters cross his threshold. Deep browns and yellows suggest decaying, moldering surfaces; even Grant’s patchwork cardigan looks like it’s trying too hard to seem cheerful. The Dolby Atmos soundtrack renders dialogue clearly, but also fills those awkward, uncomfortable silences with unsettling environmental noises. Beck and Woods even manage to make ventilation sound creepy.

A24’s separate 4K and Blu-ray editions also include audio commentary from the filmmakers, the 15-minute “Seeing Is Believing: Behind the Scenes of Heretic” that hits the expected notes but doesn’t dig too deeply into the film, and the now-standard set of photo cards. In Canada, VVS Films has released its own Blu-ray which apparently includes multiple featurettes and additional cast and crew interviews. I will investigate.

My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock is now available on Blu-ray from Cohen Media Group; Heretic is available in individual 4K and Blu-ray editions directly from A24 in the US, and on Blu-ray from VVS Films in Canada. (Like I said.)

Up next: Wicked and Juror No. 2 offer very different takes on what today's audiences want. And they’re both on disc this week! See, I can find connections in almost anything.