Hackman Now, Hill Later

In which Norm finally finishes working his way through Imprint's Gene Hackman box.

Last month, just before we started packing up the house, another box from Via Vision arrived, containing the boxed sets Directed by Walter Hill and Film Focus: Gene Hackman. I’ve been working my way through them for weeks, watching films in between other things and sneaking the supplements in late at night.

And then TIFF swallowed up all of my time, so this column – which I’d hoped to release in early September – now arrives much later in the month, when the Hill set has, unfortunately, sold out. You can still find copies at more savvy retailers, including Bay Street Video in Toronto (as of this writing, anyway), so get on that right away while I finish up the piece; this is a set worth having. So is the Hackman, though the choices are a little more … eclectic.

Film Focus: Gene Hackman rounds up four features Hackman made in the 1970s, in between art-house obscurities like The French Connection, Scarecrow, The Conversation, Night Moves and Superman. I Never Sang For My Father, Bite the Bullet, The Domino Principle and March Or Die are gathered up for our consideration as a testament to Hackman’s range and the eclectic choices available to an Oscar-winning actor at the peak of his marketability. Basically he had his pick of projects, and he chose … all of them.

Seriously, it’s incredible how busy Hackman was in the ’70s, and how many different genres he played around in. Did you know he made three movies with Candice Bergen in the space of six years? I didn’t, because I had no idea The Domino Principle even existed until it was announced for this box. But we’ll get to that.

First, there’s I Never Sang for My Father, which makes its Blu-ray debut in this collection – a movie I’d never seen, but remembered vividly as a video-store staple back in the VHS days, its jacket art feeling like an afterthought. A few years later, I found Roger Ebert’s review in one of his collections and figured I’d get around to watching the movie someday; other stuff came along instead. And now I’ve finally caught up to it, I’m sort of glad I didn’t see it before my own father and I figured each other out.

Based on Robert Anderson’s semiautobiographical stage play, I Never Sang for My Father is about the codependent relationship of a widower named Gene, played by Hackman, and his aging father Tom, played by Melvyn Douglas – once the mayor of their town, and whose former identity as a very important person has fed his selfish, domineering personality for decades since. But he’s older now, and smaller, though he refuses to acknowledge it; he refuses to acknowledge a lot of things, including how the fact of his wife’s death, early in the story, means he has to fully reassess how he will live the rest of his life. Tom expects Gene will move back home and take care of him; after all, what else does he have to do? But Gene, having spent his entire life looking for the acknowledgment and affection his father never provided, is finally in a place where he might consider escaping the gravitational pull of his old man’s anger.

Directed by Gilbert Cates, who’s best known as the producer of a couple of decades’ worth of Oscar telecasts, it’s a small, focused drama with no greater ambition than to bring the play to the screen with an excellent cast: In addition to Hackman and Douglas, the film version also features Estelle Parsons in a small role as Gene’s sister Alice and Dorothy Stickney as their mother Margaret. It’s a little bland – it looks like it was shot for television, if I’m being honest – but that’s fine.

It’s all about the text and the performances, and Hackman’s willingness to play against his innate likability and really dig into the resentment that drives Gene makes this a perfect role for him. He’s spent his entire life straining under the sense of filial expectation his father instilled in him, and is just beginning to question why that expectation only goes one way. And Gene’s ultimate solution to the problem of caring for Tom is the sort of thing that can only happen in fiction, but it so clearly speaks to Anderson’s reasons for writing the play in the first place.

The disc offers no supplemental material, but the film doesn’t need any. It says everything it needs to say.

The other three films in the set aren't quite as distinguished: They’re mid-range genre projects with high concepts and all-star(ish) casts aimed at adult audiences. In other words, they’re the sort of picture They Don’t Make Any More, because it’s no longer possible to put a couple of solid actors in a turn-of-the-century horse race drama and expect people to wander over on date night.

That’s Bite the Bullet, anyway, a quietly revisionist Western from 1975 which casts Hackman and Bergen (and James Coburn, and Jan-Michael Vincent, and Ben Johnson and more besides) as participants in a 1906 race across the American Southeast alongside a railroad line; written and directed by Richard Brooks, who I’ve always associated with In Cold Blood but who had a wide and varied career, it’s an odd little movie that’s more interested in quiet moments between its characters than big set pieces, offering the actors the chance to flesh out a collection of carefully arrayed stereotypes.

But that’s why Hackman’s so good in it; as a former Rough Rider who’s seen his share of misery – and, it’s implied, contributed to considerably more than his share of it – he grounds the picture in regret and hard-earned wisdom, suggesting all of this is just a way for him and his friends to pretend they still matter as the sun sets on the West.

Casting is also essential to The Domino Principle and March or Die, since neither of these 1977 releases is exactly thoughtfully scripted. Both films come from the stable of Sir Lew Grade, who cranked out a whole mess of features from the mid-’70s to the early ’90s – usually building them around a simple concept and an internationally marketable cast, shooting in exotic locations. My dude had a formula, and it worked more often than it didn’t; he also backed Jim Henson on the first two Muppet movies, making him the closest thing cinema has to a modern saint.

March or Die is his French Foreign Legion picture, with Hackman playing another disillusioned leader; here, he’s an American in exile with the Legion, having led thousands of his own men to their deaths in WWI. Now a cynical drunk, he’s ordered to retake the Moroccan city of Rif to re-establish French rule, overseeing a platoon that includes new recruits Terence Hill (as the wiseass rule-breaker who learns the value of discipline and esprit de corps) and future Superman II hulk Jack O’Halloran. It does not go well.

Directed (and co-written, and co-produced) by Dick Richards, who’d given Grade his first breakthrough hit with the Raymond Chandler adaptation Farewell, My Lovely, March or Die isn’t especially memorable; it’s basically a remix of Zulu with a little more spawl and a few more recognizable faces: Catherine Deneuve! Ian Holm! Max Von Sydow! But it takes its story seriously, and the actors are all putting the work in. Maurice Jarré’s score is rich and occasionally thoughtful, and cinematographer John Alcott – fresh off Barry Lyndon – makes it look great.

I should also mention March or Die occupies a special place in my heart because it’s the first movie I remember watching in the projection booth of the Orpheum when I was a kid – and the first time I understood cinema as a physical, tactile thing as well as something that happens on a screen. I was up there because the movie was deemed too mature for nine-year-old me, which was probably fair. But now I’m always disappointed it isn’t as violent as I imagined it to be.

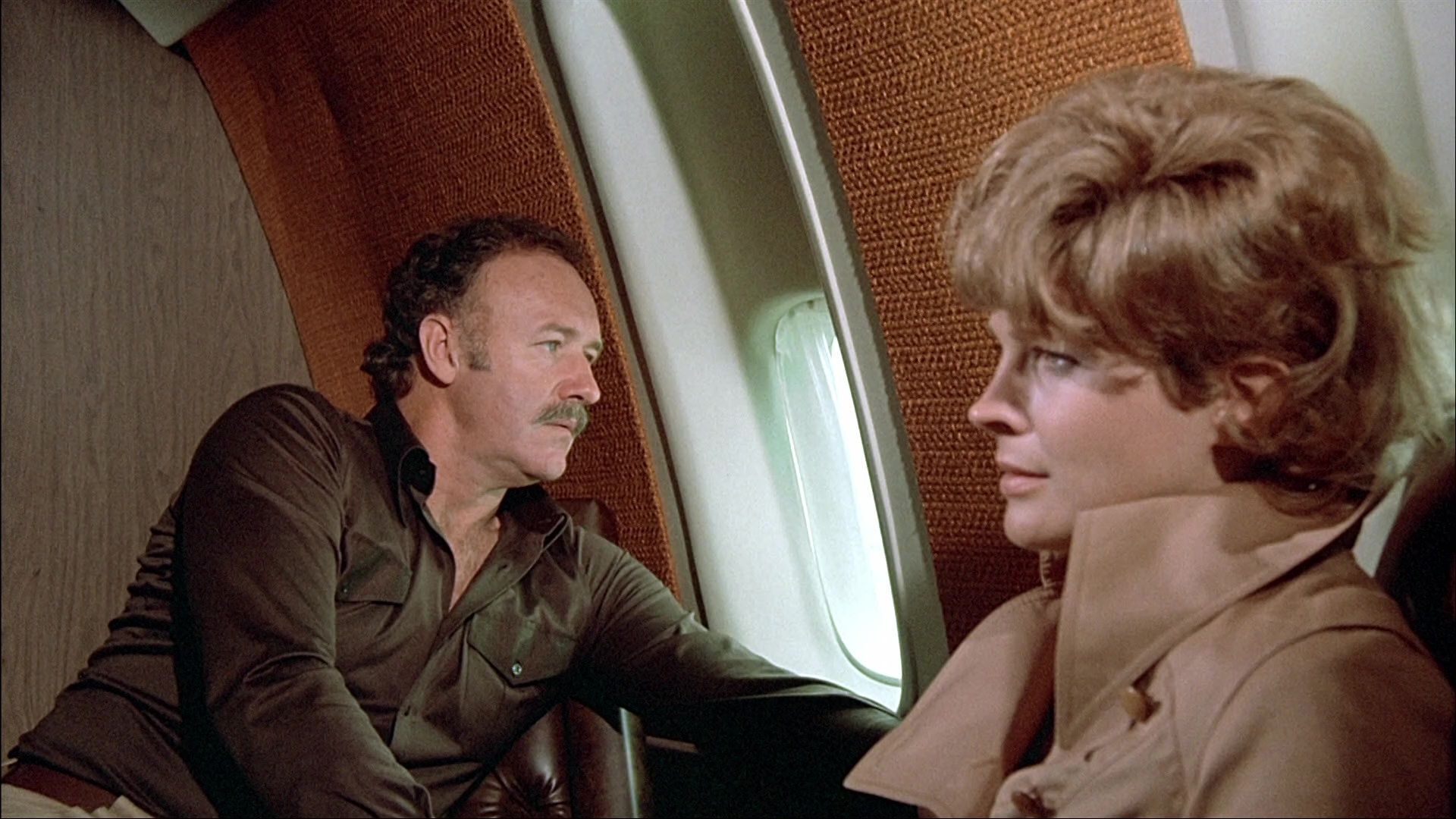

Which brings me around to The Domino Principle, and how just plain weird that movie is. A conspiracy thriller designed along similar lines as The Conversation, The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor, the film lays out an elaborate narrative about a shadowy operation of men in suits who manipulate the levers of power behind the scenes, picking unsuspecting patsies to do the messy stuff. Hackman’s Roy Tucker is just their latest mark; sitting in prison for murdering his ex-wife Ellie’s new husband, he’s approached by a man named Tagge (Richard Widmark, cool as a cucumber) with a very tempting proposition: Tagge represents a group that’ll get Roy out of prison, set him up with a new identity, a new life and a small fortune and even reunite him with Ellie (Bergen again), as long as he agrees he’ll do a job for them in a few months. The nature of the job is unknown; all he knows is that when the time comes, he can’t refuse. Roy agrees, and is relocated to San Francisco and then to Costa Rica, where he’s joined by Ellie; they spend a while together before Tagge comes calling.

Given that The Domino Principle opens with a fairly hysterical prologue – a sort of Godardian montage about assassinations and mind control which asks the viewer whether they can be sure they chose to come and see this film of their own free will – there’s not much question about the nature of Roy’s bargain, or where things are headed. But while all those other paranoid thrillers build to a fever pitch of panic, their heroes trying to stay ahead of their relentless, all-knowing enemies as the clock ticks down, this film is a curiously calm experience. Almost distressingly so.

Directed by Stanley Kramer, master of the ’60s message picture – Inherit the Wind, Judgment at Nuremberg, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner – The Domino Principle is, to put it bluntly, one of the squarest movies I’ve ever seen. It’s as though Kramer saw The Parallax View, didn’t understand its aesthetic of slow-cooking weirdness but figured he could just plow straight through Adam Kennedy’s novel as it was on the page.

And on that level, it’s a fascinating watch; almost nothing happens for the entire picture, which just follows Roy through a series of cryptic conversations. Mickey Rooney is there, as Roy’s foul-mouthed cellmate; Edward Albert turns up as a prissy brainiac to whom Roy takes an immediate dislike, requiring a genial Eli Wallach to come in and smooth things over more than once. Hackman’s entire performance here is that of a thug who’s trying very hard not to deck the people who promise him his freedom, and he nails it; his constant disdain is downright charming, and the warmth he has with Bergen in their few scenes together feels genuine. I don’t know that I actually like the movie, but I liked the experience of watching it; like Mike Hodges’ Croupier, it leaves us with the sense of larger wheels turning just beyond the frame, inexorable and unstoppable. Pretending you have a say in their direction just makes it worse.

I’m glad these films are being packaged this way, since on their own they’d kind of evaporate, the stuff of limited edition double-features. (March and Domino were previously released on Blu-ray as just that, paired with the other Lew Grade joints Escape to Athena and The Cassandra Crossing, respectively.) The Imprint box affords them a certain respectability, with good-to-great presentations and a sprinkling of supplements on Domino and March: Commentary tracks by Howard Berger and David Nicholson-Fajardo on the former and Berger and Steve Mitchell on the latter, video essays on Kramer and Richards by Berger, and interviews with Kramer’s widow Karen Sharpe and March co-star Paul Sherman. There’s also a vintage featurette for The Domino Principle that promises a very different experience than the film delivers. But that’s showbiz, I guess.

It’s a shame that neither the Hackman box nor the Hill set includes Geronimo: An American Legend, the 1993 film that marks their only collaboration; I assume it’s a licensing thing, or maybe Sony’s working on a 4K edition that won’t be ready for a while yet. In any case, it’s too bad the film’s 30th anniversary goes unremarked upon; it’s a weird film but a good one, in the way that all of Hill’s later work is. So it goes.

Coming soon: Walter Hill, at last. And also a couple of other things.