Little Treasures

In which Norm spins up the new Criterion edition of SAVING FACE, and Imprint's remarkable boxed set of BLUE and FADE IN.

Some movies sneak up on you, you know? Not everything has the wallop of an instant classic; a lot of pictures are just pretty good in the moment, and then drift away without leaving much of an impression, Then you come back to them, months or years later, and realize there’s something worthy there. In recent weeks a few such films have made their Blu-ray debuts, finally getting the special-edition treatment they deserve.

Let’s start with the deceptively modest Saving Face, which was inaugurated into the Criterion Collection just last week. The feature debut of writer-director Alice Wu, the 2004 charmer juggles two familiar indie narratives – the casually queer contemporary romance, and the generational family drama – in the story of Wil (Michelle Krusiec), a closeted surgical resident in New York whose budding romance with the more confident dancer Vivian (Lynn Chen) is threatened when Wil’s more traditional mother, the widowed Hwei-lan (Joan Chen), shows up on her doorstep, pregnant and ready to move in. She won’t say who the father is, and she’s annoyed that Wil would even ask. Boundaries established, Wil agrees to let her mother stay until they can figure things out.

I was on the FIPRESCI jury when Saving Face premiered at TIFF that year, and its lighter touch didn’t land as well with some of my colleagues. Me, I called it a perfect indie fusion of Double Happiness and Better Than Chocolate, and I still think that was apt – though with hindsight The Wedding Banquet seems like an obvious touchstone as well, since Wu’s script tackles some of the same culture clashes explored in Ang Lee and James Schamus’ picture. The characters of Saving Face are so determined to meet their parents or grandparents’ expectations that they risk abandoning everything that makes their life worth living – until they realize what actually matters most.

Wu’s movie is ultimately about inculcated shame, and how traditionalism harms us more than helps us now that we no longer live in tiny villages. Both Wil and her mother are driven by the same self-loathing, passed down from Hwei-lan’s father (Jin Wang), whose first instinct when informed of Hwei-lan’s pregnancy is to disown her loudly enough for the neighbors to hear; it’s no wonder Wil hasn’t come out to him.

And we can see how that self-negation has damaged Wil in other ways, even to the point of rendering her unable to advocate for her own desires – for her own personhood, really – in her relationships with the people who are supposed to be closest to her. Wil seems more comfortable gently torturing her mother by setting her up on some dates than she does in her intimate moments with Vivian … though Vivian is determined to help her open up. She’s very perceptive that way.

Criterion’s special edition of Saving Face is available in Blu-ray only, supporting a very good presentation of the feature with a mix of new and archival supplements. Alice Wu’s commentary is ported over from the 2005 DVD, along with a few deleted scenes, a production featurette and footage of the movie’s Sundance premiere (which happened four months after TIFF, but whatever).

And Criterion has commissioned new interviews with Alice Wu and Joan Chen in which director and star reflect on the movie and its impact on their respective careers. (It would be fifteen years before Wu made another feature – The Half of It, a very clever queer teen spin on Cyrano de Bergerac – and that’s a shame.)

Both segments are thoughtful and even surprising – I always forget Chen grew up in Mao-era China, and the unique perspective that gives her on the cultural divide – but I’m kind of surprised that Krusiec didn’t get her own segment; she does play the central character, after all, and she’s still out there making movies, recently turning up as Andrea Bang’s supportive aunt in the romantic drama Float. Maybe the scheduling didn’t work out, but without Krusiec this release can’t help but feel incomplete.

Now, you want something complete? I’ll give you complete: Last month, the always-surprising Australian distributor Via Vision added a double-feature of the Paramount curios Blue and Fade In to their Imprint Collection label, packaged as a three-disc set. If you’ve never heard of these films – and you very likely haven’t – here are three names that should catch your interest: Terence Stamp, Burt Reynolds and Barbara Loden.

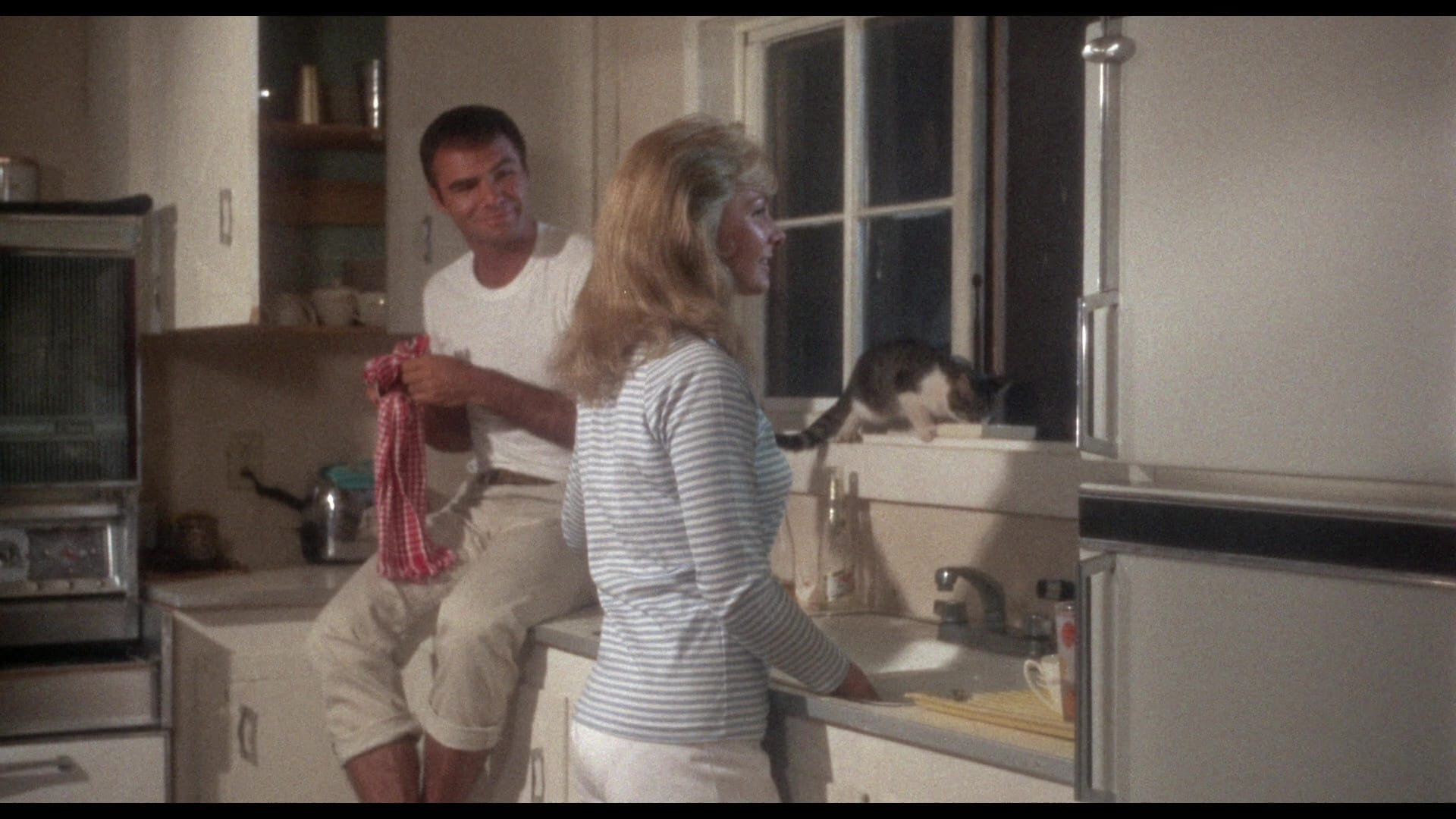

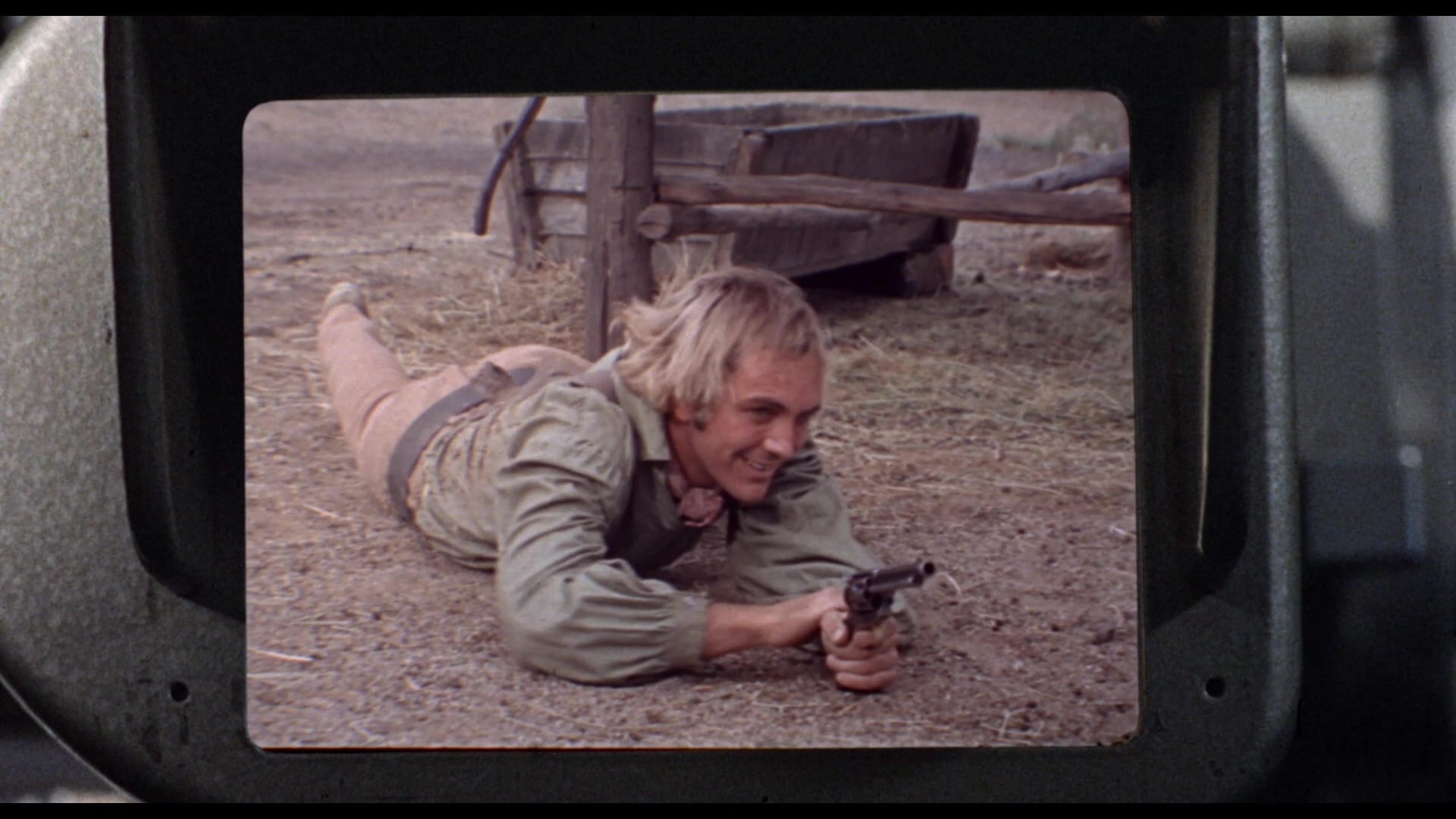

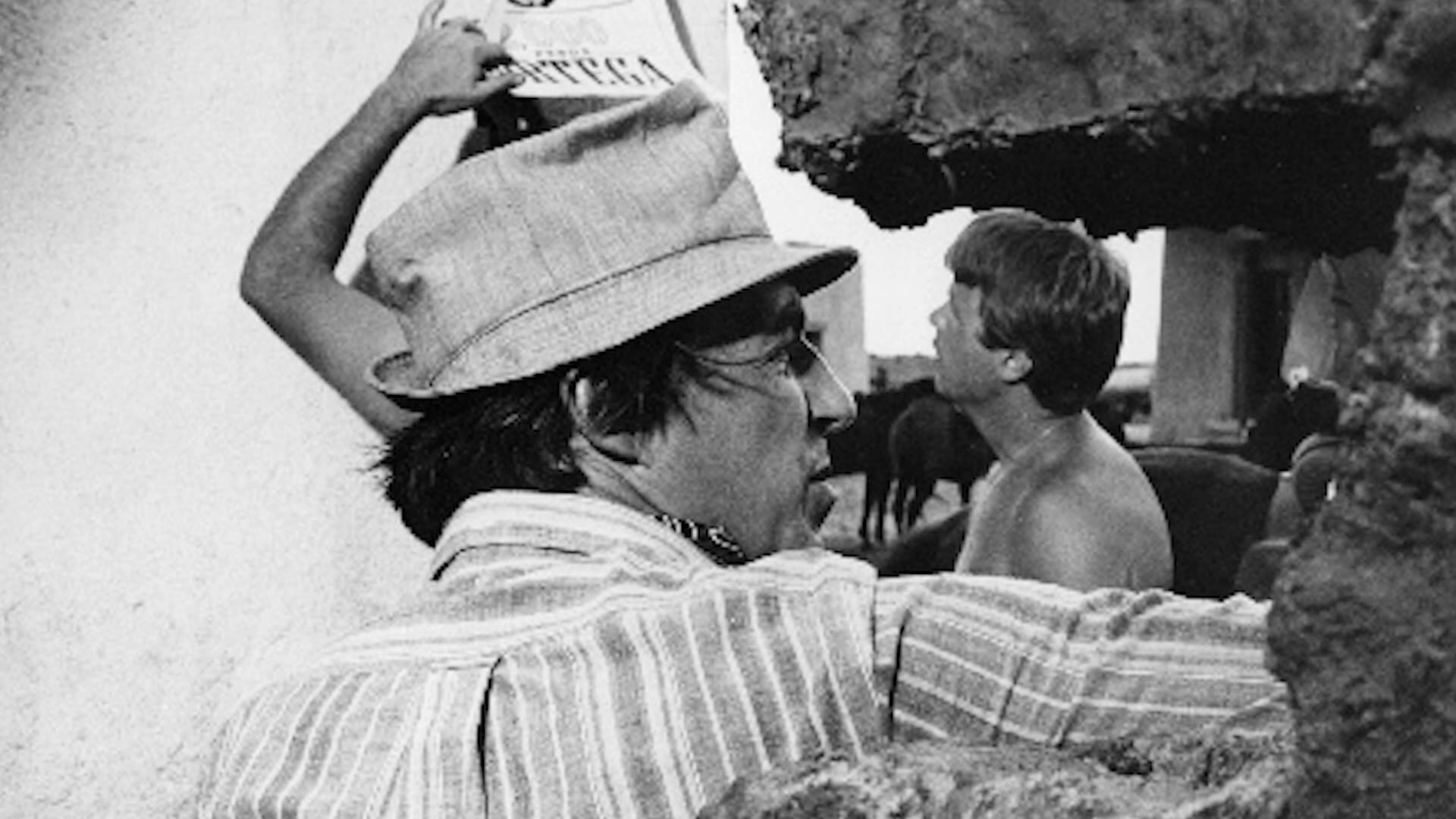

Stamp is the star of Blue, playing the adopted son of a stoic Mexican revolutionary in 1880 – it’s a long story – who has a crisis of conscience during a border raid, gives up his violent ways and tries to settle down with a nice young pioneer (Joanna Pettet), only to find his past won’t let him go so easily. And while Silvio Narizzano was making his period Western, the cameras were also rolling on director Jud Taylor’s Fade In, starring Loden as an assistant editor working on Blue and Reynolds as a local cowhand hired as a driver for the shoot.

Fade In was literally produced in Blue’s shadow, with Reynolds and Loden walking through the set and production offices and even bumping into the odd cast member as their own romance blossoms; it’s fascinating, really, since watching Fade In serves to good-naturedly puncture the seriousness of Blue over and over again. And if you’re wondering why no one else has tried to make something like this, it might be because Fade In was smothered by the studio, recut against Taylor’s wishes and dumped to TV six years after it was shot to cash in on Reynolds’ rising star.

While we’ll never know what Fade In might have looked like in Jud Taylor’s cut rather than as An Alan Smithee Film, the studio version is pretty damn charming, driven by the undeniable chemistry between Reynolds and Loden and the casual buzz of the production around them. A television director, Taylor has a great eye for crews and activity; he also has a small-screen sensibility that might have fallen a little flat at the time, but feels nicely intimate now. Even small movies shot in 1967 look more interesting than most mass-market stuff these days.

Blue, on the other hand, is a properly impressive Western – beautifully photographed in scope by Stanley Cortez, and directed with verve by Narizzano, the Canadian journeyman whose diverse filmography included Die! Die! My Darling! and Georgy Girl before it, and Redneck and Why Shoot the Teacher afterward. Georgy Girl is understandably the film people remember best, but Blue ought to be talked about too; the script is a little on the stiff side, but the unlikely presence of Stamp brings an alien beauty to the story – especially since his character, Azul, is a man of very few words.

Robert Redford was supposed to play the role, and while I’m sure he would have been perfectly fine, Stamp is doing something much weirder. This guy doesn’t think he belongs anywhere, with anyone, and Narizzano captures Azul’s squirming discomfort in every scene.

Paramount provided recent 4K scans for both features, and while Fade In was released on BD not long ago by Kino Lorber, this is the first time Blue has been made available in 1080p, and it’s a beauty. I really hope there’s a proper UHD disc coming at some point, because Cortez’ cinematography is just magnificent, with its sprawling compositions, rich colors and eerie day-for-night textures.

Fade In doesn’t fare quite as well, with some visible wear in certain shots and a softer image overall; my first thought was that the transfer was sourced from a well-preserved 35mm print, but since the movie was never released theatrically I suspect it’s an interpositive. Given the history of the project, I can’t say I’m surprised the materials weren’t better preserved … but at least it’s matted at 1.78:1, closer its intended big-screen presentation.

Blue was released on DVD by Paramount in a bare-bones edition back in the early 2000s, but Imprint’s BD offers substantial supplements: Critics Daniel Kramer and David Del Valle contribute a new audio commentary, and there’s a new interview with visual consultant Anthony Pratt, “Art of Blue,” as well as two audio extras: An archival interview with DP Cortez, and a new interview, “A Greek in the Wild West,” with supporting player Stathis Giallelis.

Fade In’s audio commentary – which pairs Kremer with fellow film historian Nat Segaloff – was included on the Kino Lorber disc last year, but it’s not the only extra on that platter. We also get “Road to Cinema,” an interview with producer Judd Bernard by Geoffrey Freedman that I can only describe as jarringly low-rez.

Opening with a handheld rummage through the various posters and certificates in Bernard’s study and eventually settling on an underlit low-angle shot of Bernard slumped in an armchair, it’s a visually unpleasant but reasonably engaging chat. (Bernard died in 2022, so it’s unclear when this was shot, but I’m guessing it predates the pandemic.) Bernard produced John Boorman’s Point Blank and Jerzy Skolimowski’s Deep End as well as Blue and Fade In, among others; the guy had a very interesting career. I’m a little disappointed he doesn’t dish on his greatest contribution to cinema, the Elvis caper comedy Double Trouble, but maybe Freedman is saving that for another release.

I mentioned this was a three-disc set, right? That’s because the most important special feature, Kremer’s documentary Cruel, Unusual, Necessary: The Passion of Silvio Narizzano, gets its very own Blu-ray.

Devoting two and a quarter hours to the director’s life and work, Kramer immerses us in Narizzano’s early days directing CBC television dramas in the ’50s (alongside Norman Jewison and Ted Kotcheff), then moving to the UK as part of an informal cultural exchange program. He made his first feature for Hammer in 1965 (Fanatic, aka Die! Die! My Darling, starring Tallulah Bankhead and a young Donald Sutherland), almost immediately changed gears for Georgy Girl and shifted yet again for Blue, and so on. He’d spend the next fifteen years bouncing back and forth between movies and TV, then another decade or so specializing in television, a genre chameleon who worked consistently but never really found the acclaim he deserved. In an introduction, Kremer notes he was unable to find any biographical work on Narizzano while preparing his documentary; it does feel as though he’s stuffed everything he can into the final cut.

But even then, there are supplements aplenty: Deleted sequences, extended interview sessions with talking heads Michael Murphy, Paul Carafotes, David Del Valle, Nathaniel Thompson, Howard S. Berger and Paul Lynch, and a brief remembrance of Narizzano by his dear friend Peter Medak, pulled from two 2024 interviews. (Narizzano and Judd Bernard produced Medak’s first feature, Negatives.)

All three discs are packaged in one of Imprint’s handsome hardboxes, of course. The set is clearly Kremer’s baby, and he should be awfully proud of what he’s accomplished here: This is a fine testament to the filmmaker and his forgotten legacy. And short of an actual Narizzano box, I can’t see anyone doing any better.

Up next: Two more films from the ’60s offer contrasting takes on masculinity, Warner Archive rolls out some classics, and dinosaurs walk the earth once more. See you soon!