Lost and Delirious

In which Norm ventures into Criterion's restoration of INLAND EMPIRE.

In January of 2007, I sat on the FIPRESCI jury at the Palm Springs Film Festival. It was a great gig, and not just because a Southern California resort town is a magnificent way to escape the miserable depths of a Toronto winter; the movies were especially rich that year, with a wealth of international cinema – including Paul Verhoeven’s Black Book, Matias Bize’s In Bed, Susanne Bier’s After the Wedding and Guillermo Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, our eventual prizewinner – jockeying for everyone’s attention.

But there were also some American premieres, and on the last weekend of the festival I made time to catch David Lynch’s Inland Empire, which was screening on one of the festival’s more impressive screens underneath an unassuming strip mall. The audience, like most Palm Springs audiences, was made up of well-to-do people of a certain age, all of whom had come down on a beautiful Saturday afternoon to see what that nice Laura Dern was up to.

I don’t think they knew it was a David Lynch joint; more specifically, I don’t think they knew how far Lynch had gone into pure intuitive cinema after the dreamscapes of Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr. Certainly this was his strangest and most off-putting work of his career – a decade and a half later, maybe it still is? – and despite their clear love for Dern, my audience was not into it at all.

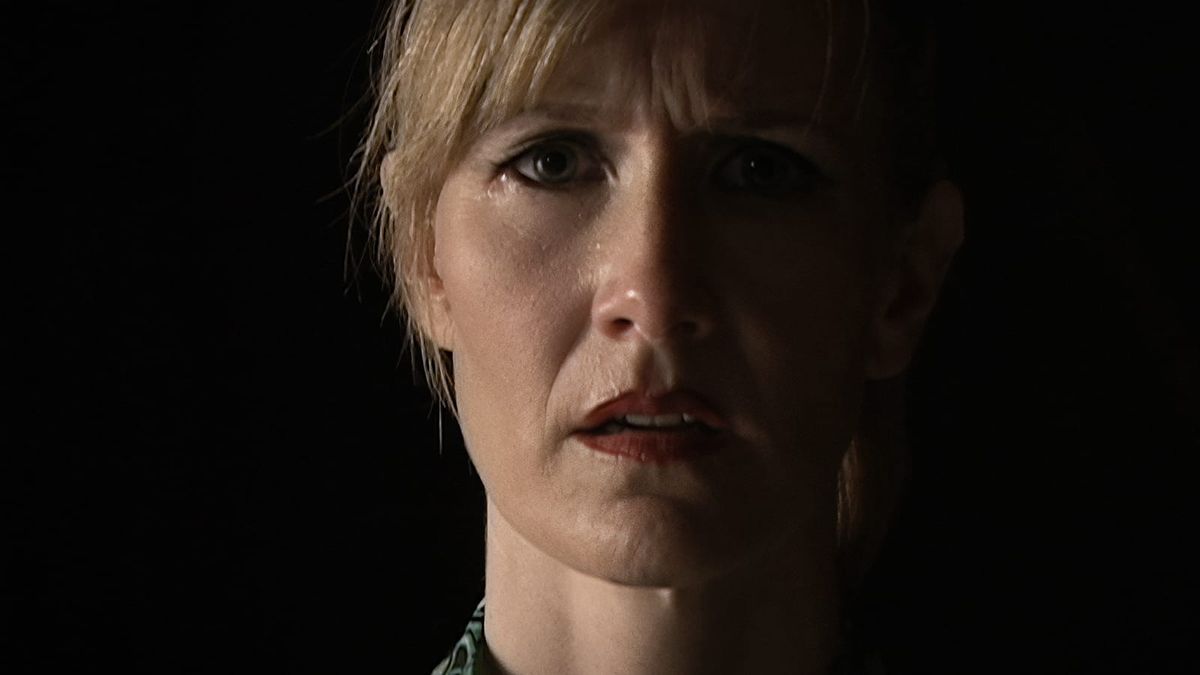

I can’t really blame them. Inland Empire is Lynch at his oddest and most eccentric, using his juice from the success of Mulholland Dr. to do whatever the hell he wants without concern for narrative structure or coherence. It’s as much about his fascination with digital cinematography and Dern’s willingness to plumb the depths of vulnerability as it is about its supposed story – which riffs on Mulholland Dr.’s confusion between performers and characters, and which, in typical Lynchian form, the filmmaker refuses to explain beyond the noirish tag line “A Woman In Trouble” – and it lurches from one ambiguous scene to the next in a way that lets you sink into its vibe without ever once caring about what’s happening.

And that’s okay. More than any other of Lynch’s projects – even more so than Twin Peaks: The Return – Inland Empire feels like something the director made for himself, just to see what would happen. The audience is incidental; this is an art installation that just happens to exist on a screen, a grab bag of Lynch’s affectations and interests that might coalesce into something if you look at it from the right angle, but almost certainly will not. I admire that opacity, and the way the airless digital aesthetic makes its actors’ faces seem as arch as the dialogue they’re exchanging. I don’t know what it all means, and I’m fine with that.

Criterion’s new Blu-ray release of Inland Empire – the film’s first HD release in North America – uses a new 4K restoration that itself feels more than a little perverse, given the project’s origins on standard-definition DV. But the new master looks remarkable, using present-day tech to highlight and even celebrate the limitations of the original image – the blown-out whites and noisy shadows, the harsh glint of lighting on metal surfaces and kickers in actors’ eyes. Lynch’s fascination with faces comes through strong and clear, Dern and co-star Justin Theroux giving everything to his camera – desperate eyes, pleading smiles, panicked gasps, you name it. I’d forgotten how wonderfully crinkly William H. Macy looks in his brief appearance; how weary Jeremy Irons seems as he tries to project artistic confidence, how sinister Harry Dean Stanton can be just by sitting around looking friendly. Everyone’s up to something in this picture, and it’s not just one Woman who’s in Trouble.

The film sits alone on Blu Ray One, with a choice of 5.1 DTS-HD or uncompressed stereo soundtracks; that’s all we’re offered, not even chapter stops. (Lynch is famously opposed to letting the viewer skip around within his work.) Blu Ray Two, however, is dense with supplemental material – though whether it enhances our specific understanding of the film it accompanies is debatable. A half-hour conversation between Dern and Kyle MacLachlan, who co-starred in Blue Velvet and have worked with Lynch on multiple projects over the decades, offers insight into the director’s methods that few other people could provide; it’s intimate in a way few supplements get to be, and there are moments when watching it feels like eavesdropping on two friends catching up after a long time away. It’s lovely.

The 2007 documentary Lynch (One) offers more direct access to Lynch’s process, as it was shot during the making of Inland Empire and finds the filmmaker in full creative flower – though, again, he doesn’t betray anything he doesn’t want to about the plot or his perspective on it. It’s a good documentary, though, and it’s accompanied here by Lynch2, a half-hour compilation of outtakes from that shoot. Both are credited to the documentary collective known as blackANDwhite, who would revisit the filmmaker for 2016’s David Lynch: The Art Life – itself already available in a Criterion edition.

The disc also includes More Things That Happened, a 75-minute compilation of deleted scenes (and improvisations, and tests) presented in a similar stream-of-consciousness arrangement as the film itself, and Lynch’s 2007 short Ballerina, which I’m pretty sure is just him playing with a new camera. The same could apply to Inland Empire as a whole, I guess, if one was feeling ungenerous. But I am not.

Inland Empire is now available on Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection. Don't hold your breath for a 4K release.

Coming next week: Paramount releases Dragonslayer in 4K and Star Trek: Strange New Worlds on Blu-ray, and I finally get to rave about Shout! Factory’s devilishly good 4K release of The Exorcist III.