Monsters: They're Just Like Us

In which Norm sinks into the darkness of Criterion's A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE and Shout! Studios' NOSFERATU, THE VAMPYRE. Tread lightly.

I’m writing this on my way back from the Windsor International Film Festival, where I’ve spent a truly fulfilling few days hosting intros and Q&As, moderating industry panels and even seeing a few movies – among them Xiaoden He’s tender Montréal, Ma Belle, which won the $25,000 WIFF Prize in Canadian Film this morning. (Xiaoden’s star, Joan Chen, was named Best Actress at the ReelWorld festival earlier this month, another well-deserved award.) When it gets a theatrical release, I’ll make sure to let you all know.

I was the host and moderator of last night’s screening, after which I went straight into a late show of Ólivier Laxe’s Sirāt, which was the polar opposite of Xiaoden’s film, at least as far as tone; a thriller about a father looking for his vanished daughter in the fringes of the North African desert-rave scene, it’s an immersive, unnerving and ultimately terrifying picture, and one of the most technically accomplished works of cinema I’ve seen this decade. Reviewing that one is going to be a challenge, because you really need to go in cold. So just trust me on this, and brace yourself for a meditation on a certain kind of European cinema that feels new and furious and elemental. See it at the biggest, loudest venue available. And ask them to turn up the bass.

Seeing Sirāt this week was a nifty contrast to the two discs I’m writing about in this edition, because if Laxe’s film is a pulverizing scream, neither David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence nor Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu, the Vampyre really raises their voice. I don’t think there’s a single jump scare in either film, despite the brutality of Cronenberg’s set pieces in the former or the grotesque nature of Klaus Kinski’s prosthetics in the latter. They just lead us into a very specific darkness, and wait for us to realize we’ve been abandoned to it.

If you focus on the logline, A History of Violence isn’t even a genre work. It’s a brooding drama about a family coming apart from within, as an ordinary married couple find themselves struggling with questions of identity, intimacy and trust. Oh, and murder.

Joining the Criterion Collection in a crystal-clear 4K restoration – all the better to honor its 20th anniversary of its release – Cronenberg’s most outwardly normal production introduces us to small-town family man Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen), who becomes a media celebrity after thugs hold up his diner. They pull their guns; Tom kills them with quick thinking and a coffee pot. It’s no big thing, he tells the reporters. Anybody would have done the same. Two jittery idiots messed with the wrong guy, that’s all.

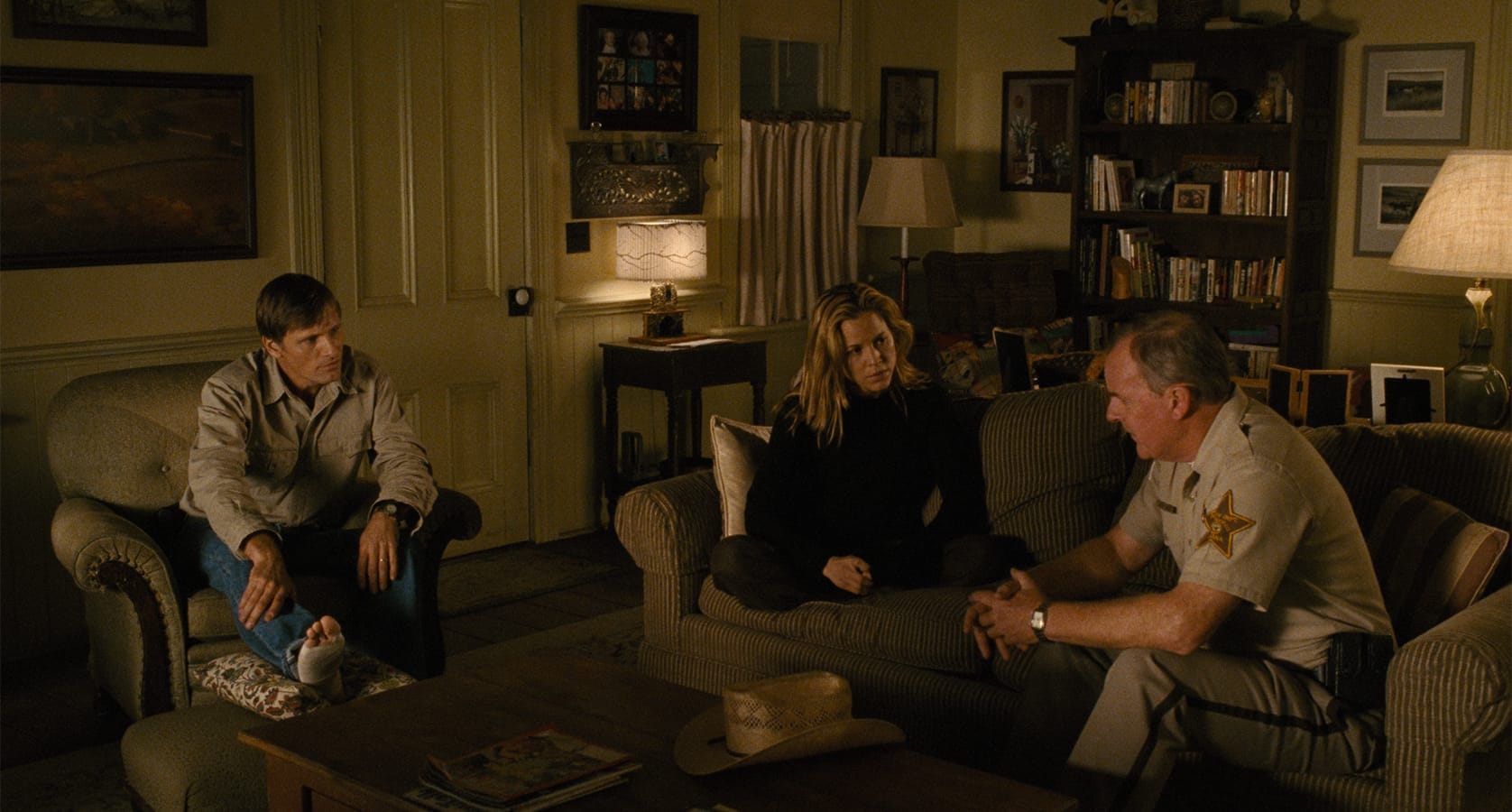

And as much as Tom wants to forget the whole thing and go back home to his wife Edie (Maria Bello), their teenage son Jack (Ashton Holmes) and his kid sister Sarah (Heidi Hayes), people have questions. Tough guys – real tough guys, calm and collected and very clearly carrying weapons they know how to use – turn up at the diner, wondering if maybe Tom isn’t who he says he is, and is in fact a long-lost associate of theirs, some guy named Joey. If he is, that’s going to be a problem. And if he isn’t, these don’t seem like the kind of people who deal well with disappointment and frustration. And so the stage is set for an old-fashioned showdown … but the results of that showdown will depend on what kind of person Tom Stall really is.

In less artful hands, Josh Olson’s script – adapted from a graphic novel by John Wagner and Vince Locke – could have formed the basis for a conventional thriller, and that is exactly how A History of Violence was marketed in 2005. But Cronenberg’s flair for the visceral, both emotionally and physically, can be felt within every frame, pushing to get out. He plays the story straight while coaxing out an unsettling subtext about the Stalls’ discovery that violence might not just be necessary but attractive, from a certain angle – and then confronting us with the ugliness of that violence, even if it’s being committed by someone we see as a good guy. Maybe he even believes it himself. Does that make things worse?

This was Cronenberg’s first collaboration with Viggo Mortensen, and they unlock something in each other. Or maybe it’s just that they share a sense of humor; not too long ago, Cronenberg told me he sees all of his movies with Mortensen as comedies. The actor seems very much on his wavelength, giving Tom just the slightest streak of Middle American blandness that could be interpreted as his own private joke. Tom laughs everything off, dismissing both praise for his heroism and accusations of past brutality with the same shrug and weak smile, as though he’s embarrassed by the idea that anyone could ever see him as a physical threat. Only maybe that isn’t embarrassment at all, but the nervousness of a man who’s found himself cornered. What might that guy be capable of?

Nathan Lee puts it beautifully in his booklet essay: “A History of Violence is one of the great films about looking someone dead in the eye and not knowing who looks back.” Even once we know who Tom Stall is, we’re still trying to understand who Tom thinks he is, and who he wants to be now.

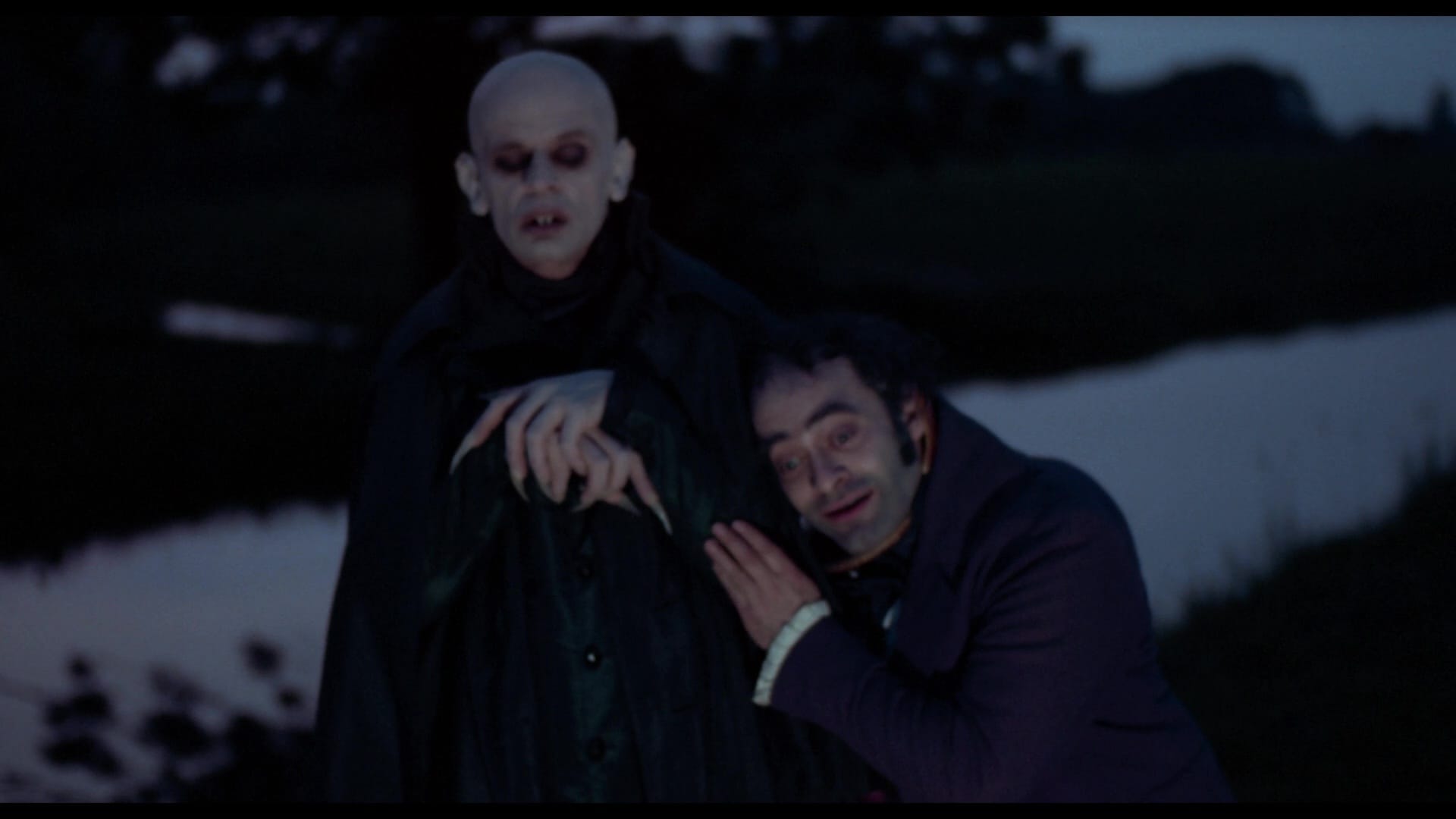

The moment Jonathan Harker meets Count Dracula in Nosferatu, we have no illusions. Kinski’s Dracula knows exactly who he is and what he wants, and he will destroy everything who stands in his way to attain it. And it’s pretty simple, really: This cultured beast plans to move from Carpathia to Harker’s home town of Wismar, where he will indulge his infernal thirst – and spread his pestilence – all over again.

Allow me to direct you to another essay, a Roger Ebert review that’s stayed with me for decades. Roger articulated Herzog’s conception of the vampire as a creature of entropy more eloquently than I ever could – and of the hundreds of movies that followed in Nosferatu ’79’s wake, I can think of just one – Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive – that’s come close to recapturing its mood. But Jarmusch has a sense of humor, and Herzog will not allow us to laugh at his monster.

Buried under latex, with bat ears, bucktooth fangs and fingernails that stretch into talons, Klaus Kinski’s Dracula is a modernization of the fiendish “Count Orlock” played by Max Shreck in F.W. Murnau’s 1922 version, and given the exaggerations of the makeup and Kinski’s own bombastic inclinations, the most unsettling thing about his performance is how restrained it is. In still images, it makes total sense: Despite working with color and sound, Herzog is staying very close to the original silent film, recreating Murnau’s aesthetic with harsh lighting, pasty faces and a minimum of dialogue.

And as Roger points out, what the characters say is ultimately irrelevant anyway – to that point that when I saw Herzog’s Nosferatu at Toronto’s Revue Cinema sometime in the late ’90s, the print they’d been shipped was the German version with French subtitles and it really didn’t blunt the experience at all. You can understand everything.

Kinski is magnificent, Bruno Ganz is vulnerable and pitiable as Harker, and Isabelle Adjani is a lustrous life-force as Harker’s heroic bride Lucy, who sacrifices herself to the beast in order to save her husband and her village. Although in this version, Lucy’s victory comes with an asterisk. Sometimes when you invite the monster in, the monster makes itself at home. A History of Violence understands that too.

Criterion’s disc collects the excellent supplemental package produced for New Line’s original DVD special edition – a great Cronenberg audio commentary, an hour-long documentary and a trio of shorter pieces – and adds a 2014 video of Cronenberg and Mortensen onstage with TIFF CEO Piers Handling at that year’s festival and a new conversation with screenwriter Josh Olson and Tom Bernardo, producer of Amazon’s hard-boiled Bosch adaptation. These guys know the value of a good coffee pot.

Scream Factory’s 4K combo of Nosferatu is built on new restorations of both the German- and English-language releases of Herzog’s film, cleansing Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein’s imagery of dust and scuffs while reveling in its grotty tactility. (The opening title sequence feels a little soft, but the leap in clarity immediately afterward is almost startling.) HDR and Dolby Vision grades allow for a much broader range of darkness and gloom; the whites of Kinski’s eyes stand out even more vividly against his pallid complexion and darkened hollows.

This release offers the same special features included on Shout’s previous Blu-rays, supporting the German version with a pair of audio commentaries from Herzog – an English track recorded for Shout, and an earlier German-language conversation with producer Laurens Straub – as well as a still gallery and an archival production featurette. And as is Shout’s custom, the Blu-ray has been re-authored with the restorations of both versions of Nosferatu. They look great, even at 1080p … but of course, the 4K presentation is so much darker. Have a torch ready.

A History of Violence is now available in the Criterion Collection in a 4K/Blu-ray combo edition; an individual Blu-ray is also available. Nosferatu: The Vampyre is now available from Shout Studios' Scream Factory imprint in a 4K/Blu-ray combo edition. They're both essential. Sorry.

Coming soon: Relay! Together! A new take on Red Sonja! And I understand some unexpected UHD box sets turned up while I was away …