No Way Home

In which Norm marks this National Day of Truth and Reconciliation by spinning up Canadian International Pictures' new Blu-ray of COLD JOURNEY.

It’s Canada’s National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, and thus the perfect time for me to write about the 50th anniversary Blu-ray of Cold Journey, which is this month’s release from Canadian International Pictures, following their excellent August disc of David Secter’s Winter Kept Us Warm.

You may not be familiar with Cold Journey. I knew it only from a few clips included in some documentary about the National Film Board of Canada a while back; I remember being surprised at the time that the NFB had ever made dramatic features.

What I didn’t know was that Cold Journey was not a complete fiction. It’s based on the true and awful story of Chanie Wenjack, a twelve-year-old Anishnaabe kid who fled the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario, on October 16th, 1966 – heading home to his family in the Marten Falls Reserve, nearly 400 miles away. He was found dead of exposure and hunger a week later.

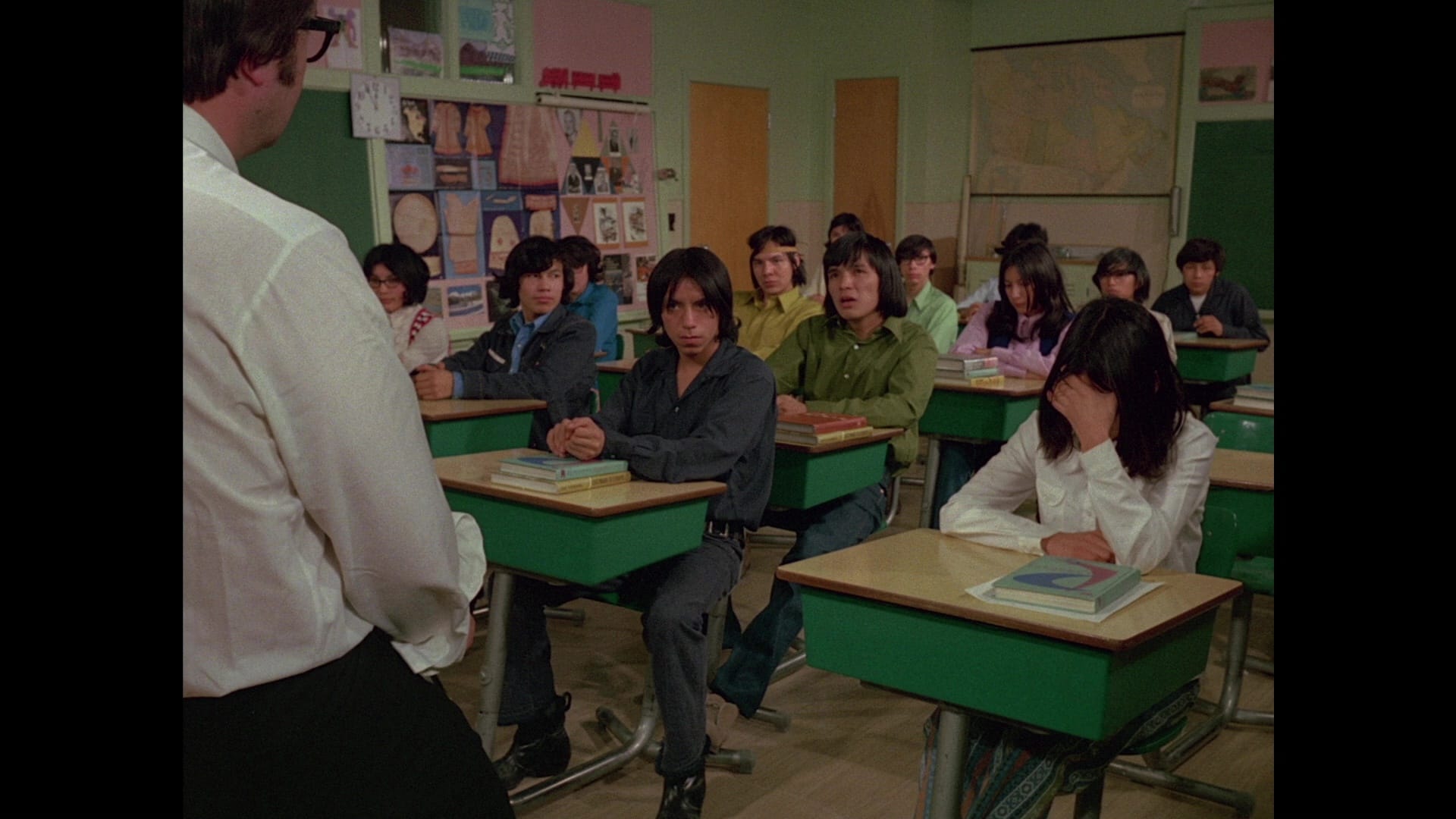

Released in 1975, Cold Journey reimagines Chanie as 15-year-old Cree kid Buckley (Buckley Petawabano), one of dozens of children stuck at a Catholic boarding school somewhere in the rural north, part of the Canadian government’s infamous attempt to re-educate generations of Indigenous people by refusing to let them engage with their language and culture, and indoctrinating them in the good clean ways of white society. And even though the film has cleaned up almost every aspect of the story it tells, the better to be palatable to white audiences, it’s clear that Buckley and his classmates are the mercy of a system that sees them only as aberrations to be corrected.

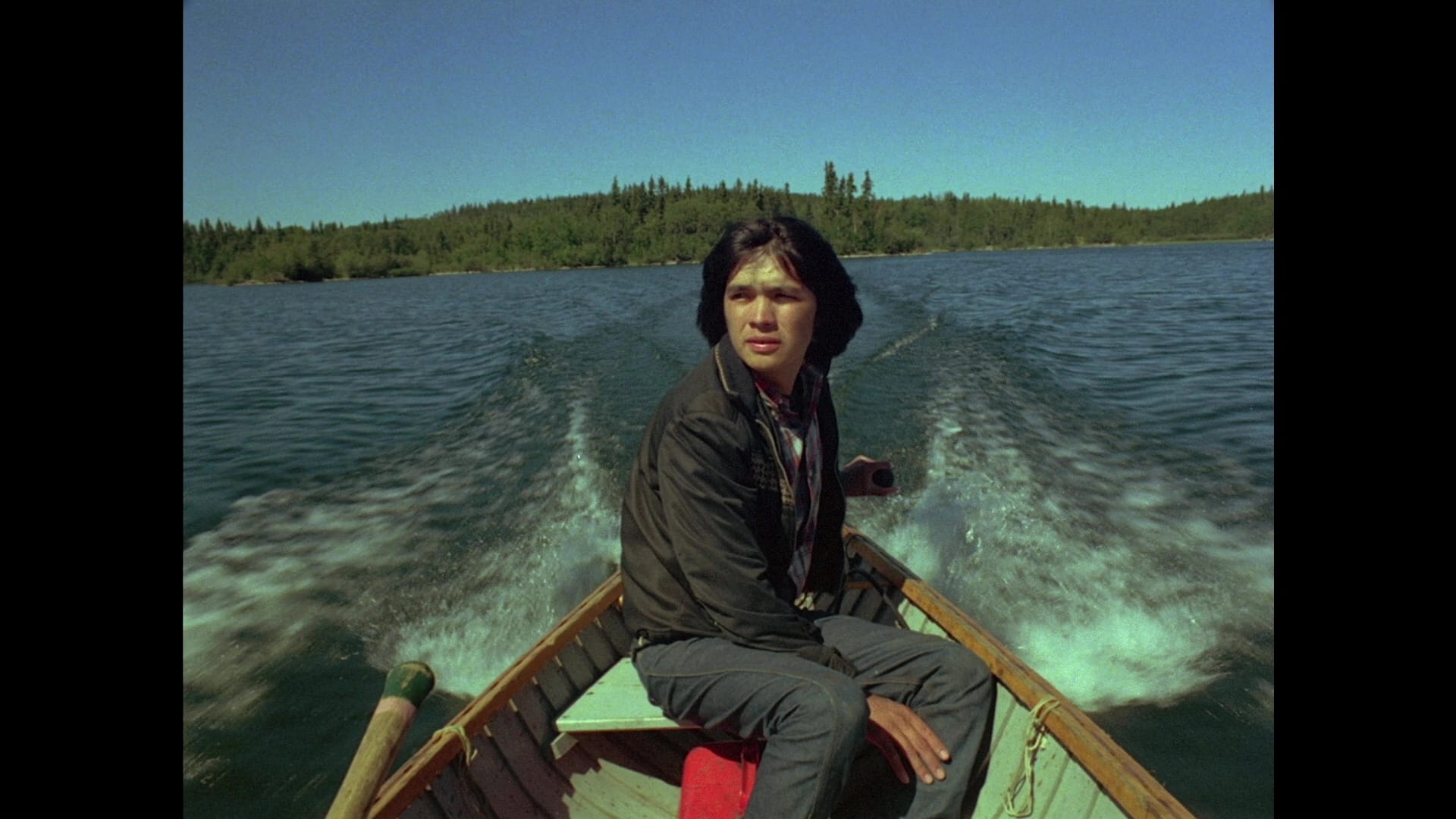

Buckley wants nothing more than to go back home, but when he returns to his community over summer break he struggles to speak the language and re-integrate into his family – which was, of course, the entire aim of the residential-school project. (And again, we’re watching a teenager struggle with this rather than the child Chanie Wenjack actually was, because showing audiences a 12-year-old broken by an institutional system would have crossed a line.)

Back at the school, he meets a sympathetic caretaker played by actor and broadcaster Johnny Yesno, of the Eabametoong First Nation, but being reminded of his origins only leads Buckley to further anguish. He acts out; he rebels. Eventually he makes a run for it. And we know what happened after that.

Cold Journey is a deeply sympathetic look at the process by which a young Indigenous man is destroyed – first psychologically, then spiritually, then physically. What’s quietly remarkable about it is that while it was directed by a white man, and produced by a federal agency run by other white men, the film makes a real effort be objective and empathetic to its Cree protagonist – even with a quasi-ethnographic voiceover – without ever tipping over into patronizing language.

As film critic and historian Jesse Wente notes in an interview commissioned for this release, “it’s a film about us that’s not made by us, but it’s trying to accommodate us and have a sense of us that most films did not bother, at that time.” (Full disclosure: I’ve known Jesse for decades, and I can’t think of another person better positioned to talk about this film, its history and its relevance in the present moment.)

And Cold Journey is all the more remarkable for having been produced at the National Film Board of Canada, which was not known for trafficking in drama. Director Martin Defalco was an old hand at documentaries and health and safety films – a few of them are included on this disc – and this was his only dramatic feature. But he didn’t deliver a complete fiction; Cold Journey is a sort of hybrid, with a verité aesthetic bleeding through Tony Ianzelo’s carefully composed cinematography.

Defalco shot on location and leaned heavily on the locals, populating his cast with non-professional actors. Even the script card reflects this documentary mindset, with David B. Jones getting “original screenplay” billing while Defalco is credited for “story outline” beneath him, alongside George Pearson as the narrator.

That aforementioned voiceover – its stentorian delivery belying the compassion of the words – is one of several ways the film tells us how to read its story. Another is the presence of Mi’kmaq folk singer Willie Dunn on the soundtrack; he also turns up on-screen for a moment. Dunn, a key member of the NFB’s Indian Film Crew, contributed three songs to Cold Journey, all performed in a mournful cadence that reminds us, over and over again, we’re watching a tragedy.

And if you're wondering how Cold Journey was received at the time, I’ll just point out most Canadians were shocked by Chanie's story all over again when Gord Downie and Jeff Lemire retold it in 2018 in their collaboration Secret Path, so ... yeah. The work never ends.

The NFB has provided a new 2K restoration of Cold Journey, mastered from the 35mm interpositive; given the nature of the production and the fact that the IP’s been in storage for fifty years, it’s an excellent transfer. (The mono soundtrack has been cleaned up a little as well.)

New supplements produced for this release include “That Unique Feeling,” the aforementioned half-hour interview with Jesse Wente – who provides context on the legacy of Willie Dunn’s music, the history of residential schools (and his own grandmother’s experience in the system) and the contributions of Indigenous collaborators to the film’s script and sense of place. Jesse also makes a case for Cold Journey as a seminal entry in the “alternate canon” of Indigenous films written or directed by non-Indigenous artists, which also includes Richard Bugajski’s Clearcut and Rolf de Heer’s Ten Canoes.

Also commissioned for this release is “Willie’s Journey,” a new interview with Dunn’s son Lawrence and Kevin Howes, producers of the Willie Dunn anthology Creation Never Sleeps, Creation Never Dies; the pair also recorded a new audio commentary for the feature.

I regret to admit I was entirely unfamiliar with Dunn, who had an incredible career – in addition to his career as a folk and protest singer, Dunn’s participation in the Indian Film Crew led to him being the NFB’s first Indigenous director in 1968 with The Ballad of Crowfoot – for which he wrote the title song, of course.

That short film is included in the supplements along with the other collaboration between Dunn and Defalco, The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company, a 1972 documentary that uses the 300th anniversary of the trading company turned national department-store chain to look behind the corporate history and talk to the Indigenous people whose communities were exploited to fuel its rise.

There’s also an episode of Alanis Obomsawin’s 1979 NFB series Sounds from Our People, presenting a 20-minute broadcast cut of Cold Journey for younger audiences. It’s bookended by an introduction by Obomsawin, and her subsequent Q&A with an audience of about a dozen children, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Watching Obomsawin explain the historical context to these kids – gently, delicately and honestly – feels as essential as the movie itself.

For a further sense of how unlikely a production Cold Journey was for the NFB, the disc also includes four shorts Defalco directed for the Board between 1966 and 1967.

Bird of Passage recounts Montreal chemical engineer Sid Miyashita’s childhood in Vancouver, his family’s experiences during World War II and his complicated relationship with his heritage – all discussed in a voiceover read by Douglas Rain with a little more edge than he’d give HAL 9000 a couple of years later.

Northern Fisherman is an ethnographic study of Indigenous fishermen in the northern prairies, offering a window on its subjects’ daily lives and traditional methods, while the science-museum documentary What in the World Is Water teaches young audiences about the environmental function of water, “from raindrops pelting the earth to the mighty cataract of Niagara.”

Finally, there’s Charlie’s Day, a fascinating workplace safety film that follows a lascivious, easily distracted orderly (Guy L’Écuyer, who has a small role in Cold Journey) through a series of potentially catastrophic mishaps with an oxygen tank.

It’s a cautionary tale for health-care professionals pitched at the level of a patronizing pantomime, and it’s perhaps the most Canadian thing I’ve ever seen. I wonder whether there are other such training films in the NFB's archives, and if there are enough to fill a Blu-ray of their own. You know, for historical value.

Cold Journey is now available on Blu-ray from Canadian International Pictures. Fifty years on, it still has a lot to say.

Up next: The Life of Chuck comes to disc. That’s a good one too.