Precision Craftsmanship

In which Norm spins up the new discs of THE PHOENICIAN SCHEME and VERMIGLIO.

What do we want from a Wes Anderson picture? Or rather, what do you want from his work? Nearly thirty years into his career, his obsessively constructed cinema is both instantly recognizable and comfortingly familiar, spinning narratives of stunted control freaks trying over and over again to bend the world to their will, and the world refusing to go along with it. That the world is just a series of meticulously arranged dioramas should have been their first clue, really.

Every one of Anderson’s films offers some combination of misguided ambition, thwarted plans, clumsy professions of love, frantic punch-ups and shredded dignity, with a depressed soliloquy or two towards the end. Sometimes love prevails, but not always. That is, I think, what people want from Anderson, and what he wants to show them; the melancholy is the point. Except for the unambiguously happy endings of Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, whose stop-motion animal heroes allow Anderson to fully connect with the innocence that runs through all of his work. He’s happiest, I think, when he doesn’t have to pretend he’s making movies for grown-ups.

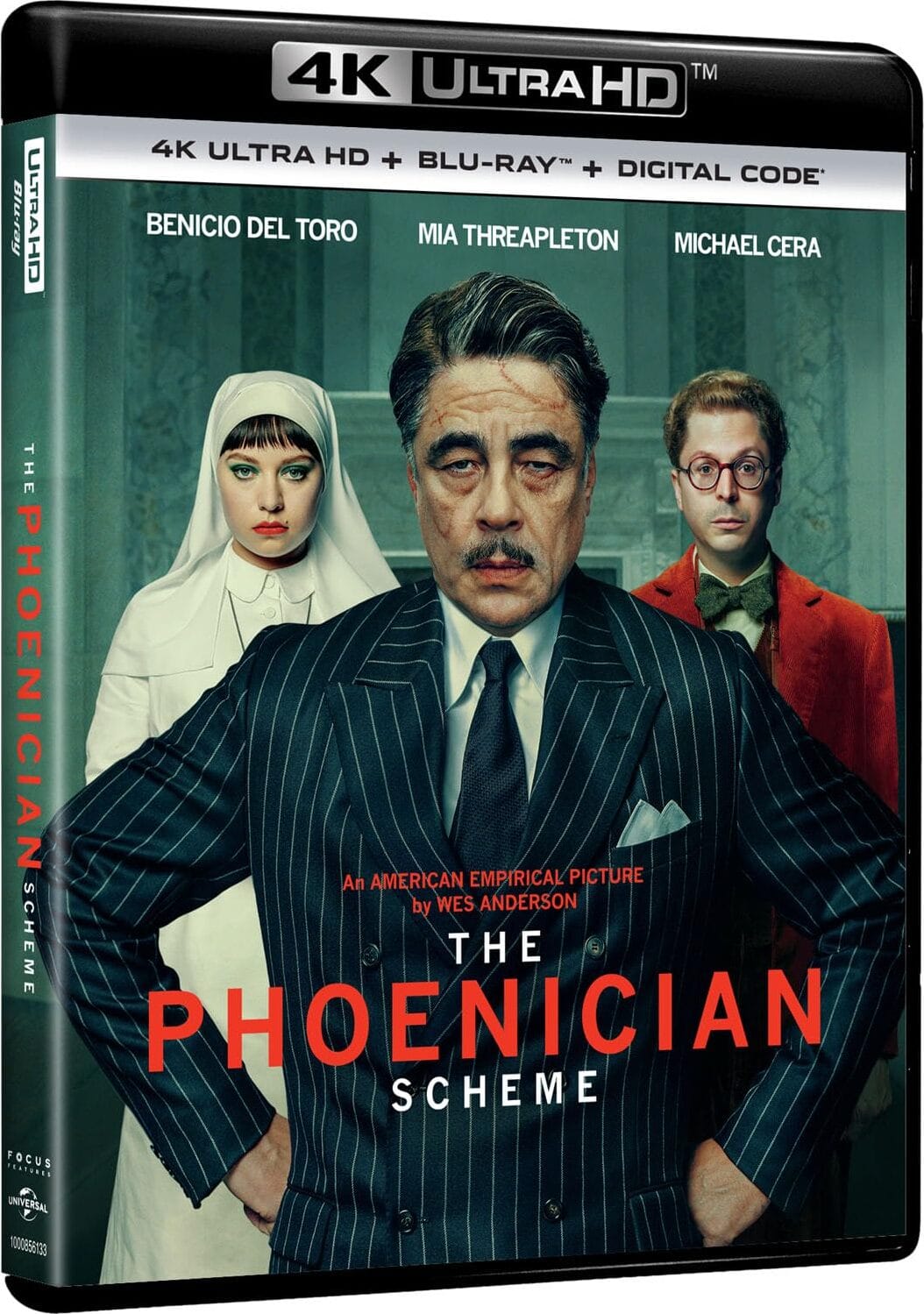

I have strayed from my thesis, which is also something an Anderson character would do. Consider Anatole “Zsa-Zsa” Korda (Benicio Del Toro), the protagonist of The Phoenician Scheme – a hard-charging European tycoon who may or may not be a huckster, a swindler, a fraud and/or a murderer.

He’s certainly a negligent father to his many young sons – and to one adult daughter, Liesel (Mia Threapleton), whom we meet as she prepares to become a nun. (It’s 1950, women still do that.) Mia believes Korda is responsible for her mother's death, and isn’t too happy about being called into his orbit as his executor – especially since Korda isn’t actually dead. But people do keep trying to kill him, so he figures Mia might as well tag along and see how his business works before someone succeeds.

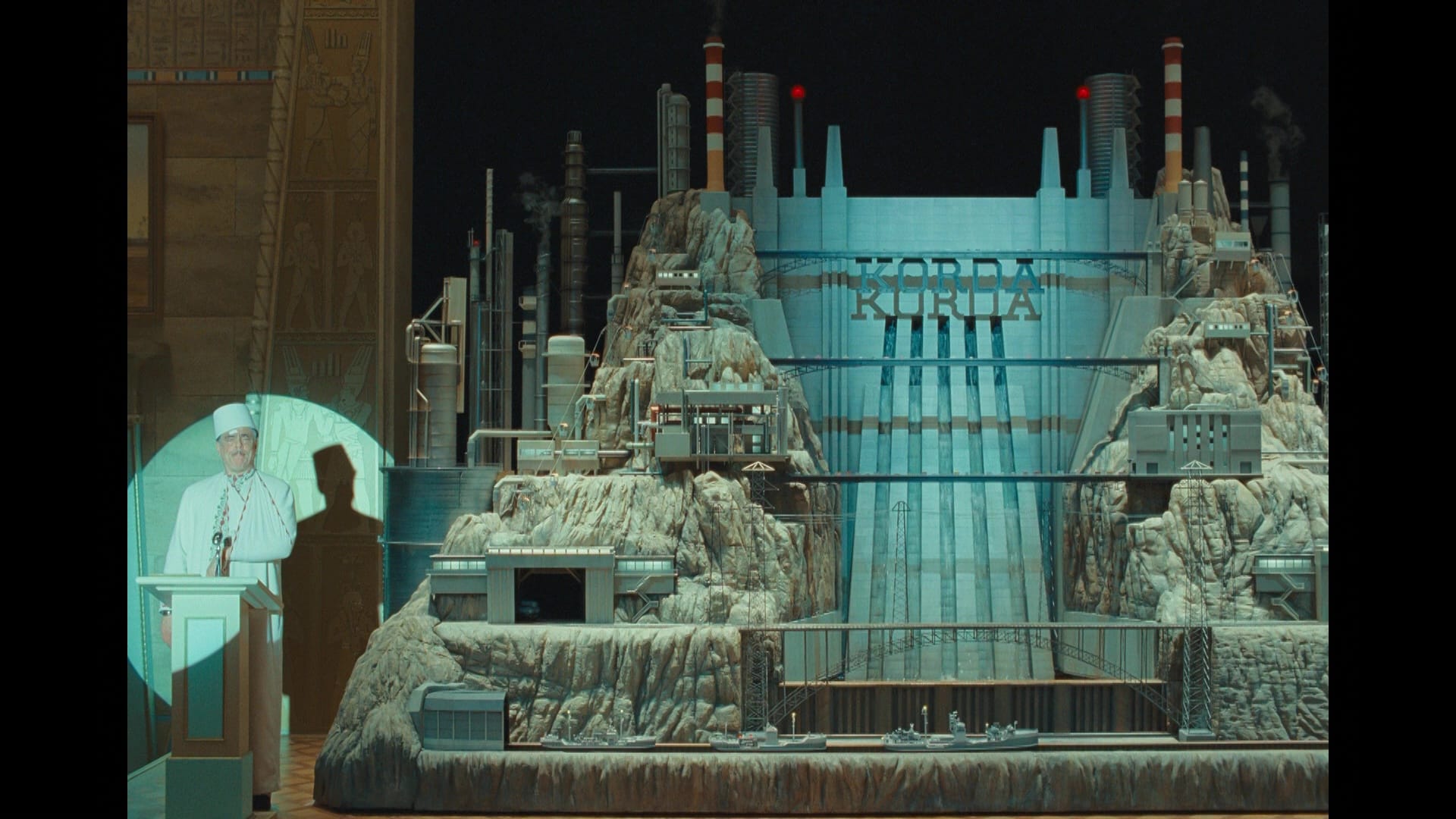

This is a very dry conceit to hang a movie on, but Anderson makes it work by making Mia’s de facto internship just one of many little ideas Korda is juggling at any given moment. There’s also his quest for self-improvement, which has led him to hire a tutor, the fussbudget Bjørn (Michael Cera), to educate him on insects and plant life, and then there’s some massive thing he’s negotiating that will transform the Continent with railroads and canals and bridges and suchlike. This project has him flying back and forth across Europe – always at the risk of assassination – to meet with various princes and tycoons played by the likes of Riz Ahmed, Mathieu Amalric, Bryan Cranston, Tom Hanks, Scarlett Johansson and Jeffrey Wright.

Also Benedict Cumberbatch is around as Korda’s half-brother and apparently untrustworthy business partner Nubar, who looks like this:

So that’s the kind of movie this is. But Wes Anderson has a repertory company, and he’s going to use it; he’s been making complex ensemble pictures ever since The Royal Tenenbaums. And who wouldn’t want to work with Wes Anderson? He’s going to give you fun clothes to wear and silly things to say, you have a lot of fun people to hang out with between shots and one assumes the craft services table is exquisite.

It's also true that Anderson knows how to deploy that massive cast to maximum effect: At this point, when Willem Dafoe first pops up – bald, bearded and scowling in the background of one of Zsa-Zsa’s Dreyeresque hallucinations – we giggle in anticipation, because we know Anderson understands how to use Dafoe’s imposing appearance for comedy, and the gag works every time because Dafoe commits so fully. But it’s also the same joke every time, and The Life Aquatic was released twenty-one years ago. You can’t blame a critic for wondering whether Anderson ran out of actual ideas a while back.

Mind you, I’m saying this as someone who called Asteroid City one of the best movies of 2023, and that was chock-full of familiar Anderson beats; it just arranged them in a more emotionally satisfying manner. I enjoyed The Phoenician Scheme just fine, in the large – its more mannered sequences aren’t as irritating as the ones in The French Dispatch, Del Toro is always enjoyable in bulldog mode and Threapleton and Cera are welcome additions to Anderson’s repertory company – but this one didn’t stay with me the way the others have. Maybe it’s that tendency towards the overtly cartoonish:

… or maybe it’s just that he needs to take more time between pictures. Michael Angelo Covino and Kyle Marvin’s Splitsville, which is in theaters this week, is almost exactly the same picture as their previous comedy The Climb, but with a bigger budget and more famous co-stars: the difference is they take five years between pictures rather than two. I admire Anderson’s industry, especially since he also made those Roald Dahl short films for Netflix the same year he released Asteroid City – but I’m starting to wonder if it’s me who needs to space out his films a little more.

Regardless, The Phoenician Scheme looks absolutely marvelous on Universal’s 4K disc – which took a month longer to make it to Canadian shelves, so apologies to American readers who’ve been waiting for me to get around to covering it.

This marks the first UHD edition of an Anderson film, and it’s a splendid disc. The 2160p presentation lets us glory in every detail of the production design, from the artfully sculpted injuries on Del Toro’s face and hands to the stitching on Cera’s tweedy wardrobe – which itself is modeled on Anderson’s own style, as you’ll notice in the on-set clips in the production featurette.

The Atmos soundtrack – another first, at least on disc – is antic and alive during the busier sequences while still retaining the intentionally modest range Anderson brings to his big action set pieces, the better to convey their weightless, innocent mayhem. And when things are quiet and contemplative, the mix enshrouds us in silence, the better to catch someone fidgeting at the other end of a room. It’s an exemplary presentation.

The sole extra is a fifteen-minute featurette, “Behind The Phoenician Scheme,” which can be viewed in four segments but plays just fine straight through, hitting the expected marks (casting, visual effects, production design, whimsy) while clearly saving any real insight for the inevitable Criterion edition that will follow a few years down the line. Is there any other filmmaker who makes such arrangements before he sets foot on a soundstage? And can you blame him? Anderson clearly loves what that label does with his movies – and that label loves him right back because their editions of his movies are always strong sellers.

Hell, next month Criterion elevates Anderson to their pantheon with a massive retrospective boxed set – making him the first American or English-language auteur to receive the honor, following Kurosawa, Bergman, Fellini, Varda and Wong. I’ve put in for a review copy, but honestly? This is one I’d be willing to pay for … though I’m still planning to wait for the Barnes & Noble sale.

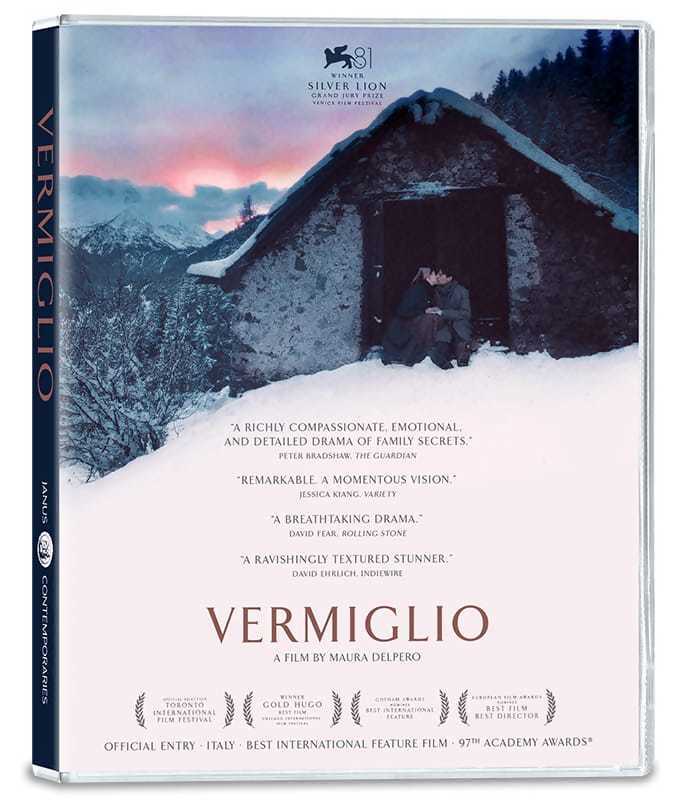

Speaking of Criterion, this week they’re adding another title to their recently rechristened Criterion Premieres imprint. (I’m led to understand “Janus Contemporaries” meant nothing to the kids.) That would be Vermiglio, Maura Delpero’s drama about events in an isolated village in the Italian Alps towards the end of Second World War.

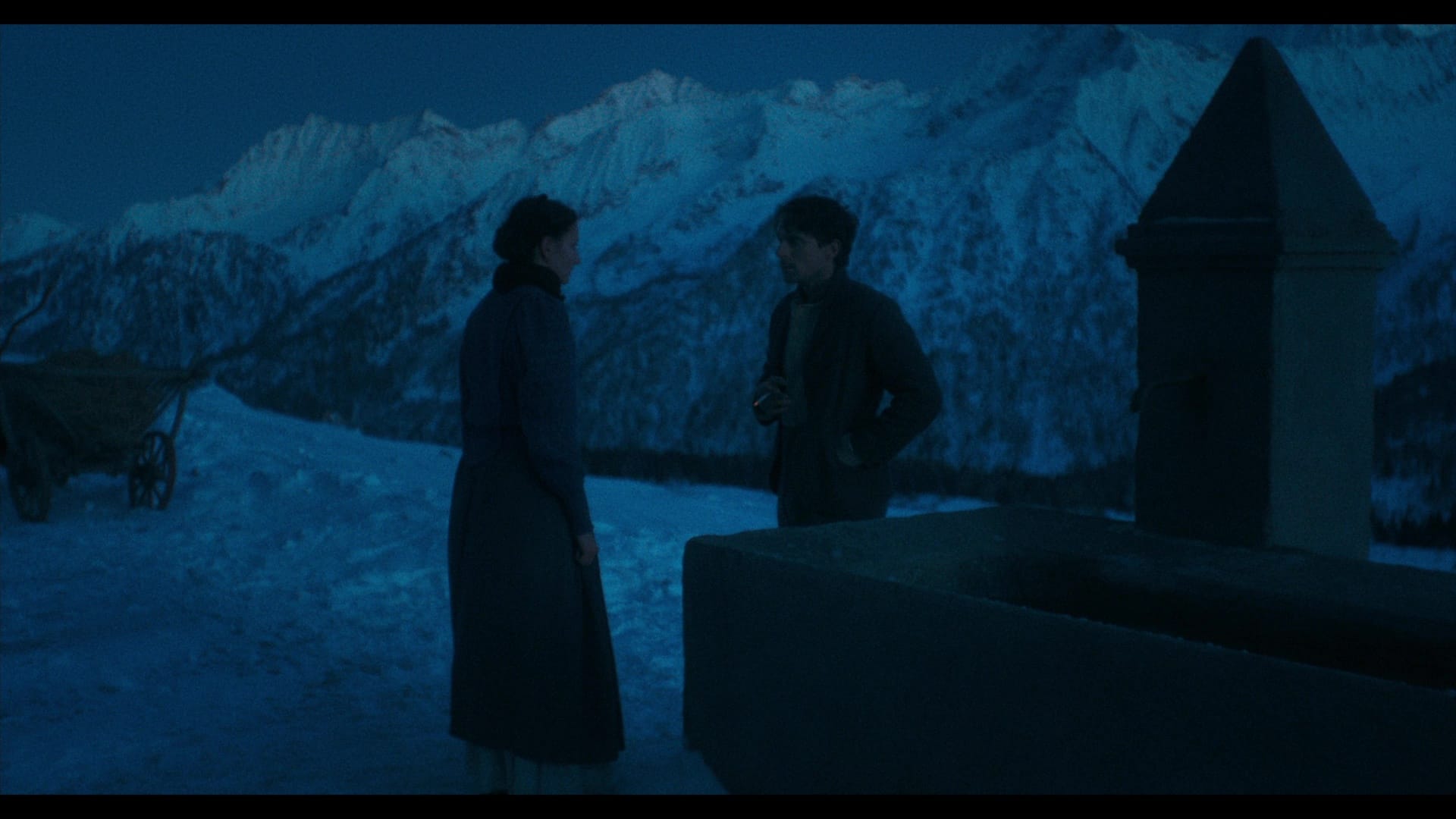

The people of Vermiglio have been waiting out the war in relative comfort; other than the absence of young men who’ve gone off to battle, you wouldn’t even know anything was amiss. And then a stranger arrives, the Sicilian deserter Pietro (Giuseppe De Domenico), bringing a wounded comrade home and hoping to stay.

Pietro’s arrival shakes things up, as he’s both an outsider and an eligible bachelor, and eventually he makes a connection with Lucia (Martina Scrinzi), the daughter of local schoolmaster Cesare (Tommaso Ragno). They marry, and things are good for a little bit. And then the war ends, and Pietro leaves to see his family in Sicily, and that is the last Lucia sees of him.

This is merely the first movement of Vermiglio, which unfolds in four chapters over the course of about a year. It’s a film that’s modest in scope but rich in feeling and detail; writer-director Delpero efficiently establishes her world and drops us into it, and Russian cinematographer Mikhail Kritchman, a frequent collaborator of Andrey Zvyagintsev, shoots the settings beautifully but casually, if that makes any sense.

The love story between Lucia and Pietro gives way to a different sort of drama, one rooted in the endless generational conflict between parents and children, tradition and progress, fear and courage. And Scrinzi, in her feature debut, holds the screen with such poise and quiet dignity that Lucia simply seems to exist in front of us, enduring heartbreak and agony and finding her strength on the other side of it. Damn fine picture, this one.

As with all of these releases, supplements are limited to a theatrical trailer and Delpero’s episode of the Criterion Channel’s Meet the Filmmakers series. It leaves one wanting more; perhaps she’ll get a full special edition for her next film, whatever that turns out to be.

The Phoenician Scheme is available in 4K/Blu-ray and BD-only editions from Universal Pictures Home Entertainment. Vermiglio is available in a Blu-ray edition from Criterion under the Criterion Premieres label. Simple, right?

Up next: Speaking of Criterion, Alice Wu’s Saving Face enters the Collection this week, and Via Vision’s latest Imprint box gives a forgotten Canadian filmmaker the showcase he deserves. See you soon!