Reclamation Time

In which Norm spins up Via Vision's Imprint special editions of NEW YORK, NEW YORK, LEADBELLY and J.W. COOP.

It’s always weird to remember that “New York, New York” isn’t, like, a hundred-year-old anthem. It’s not even half that! It was written for Liza Minnelli! By the Cabaret guys! For a Martin Scorsese movie!

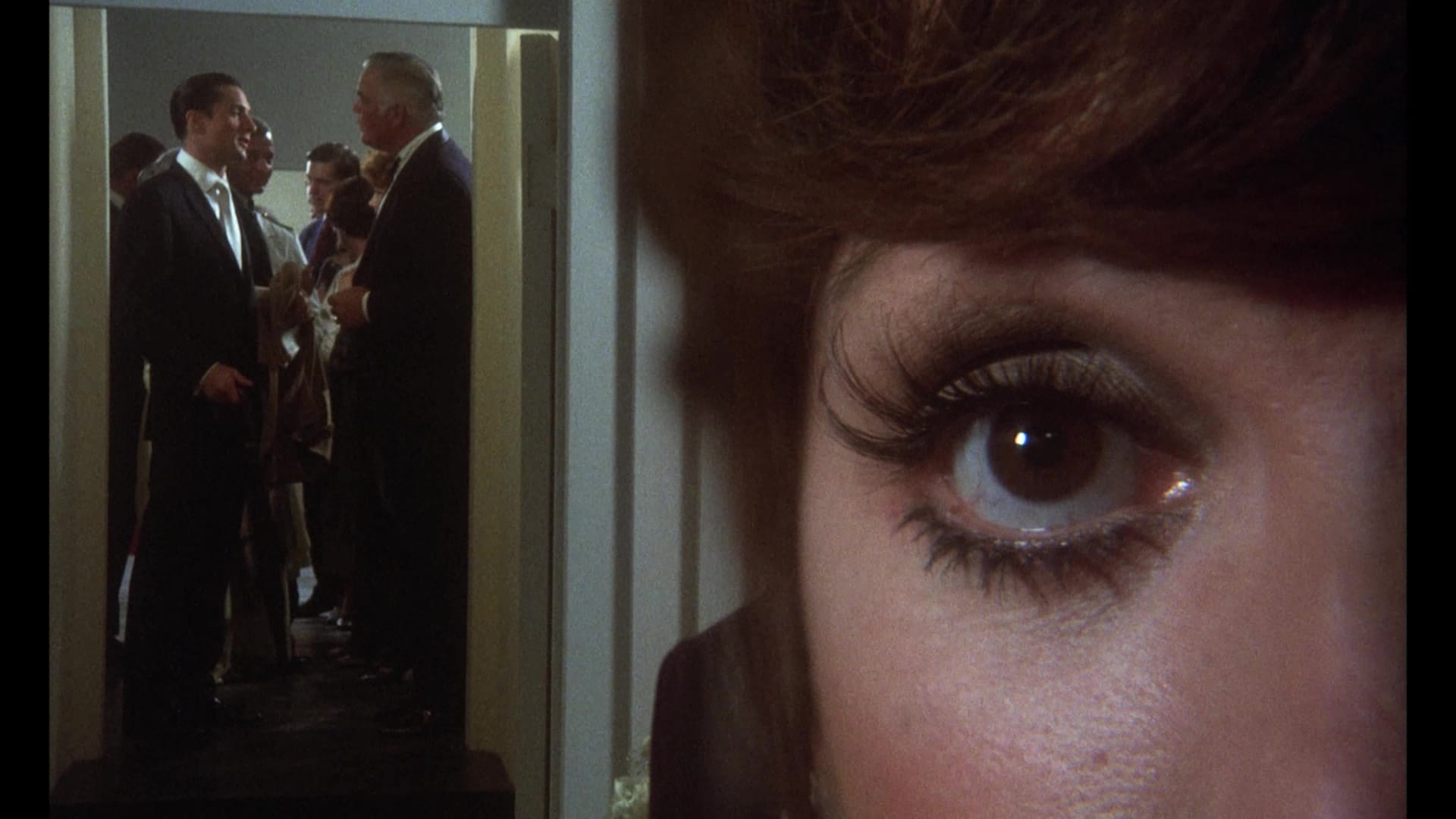

We all know this, as film lovers, but it’s still bizarre to watch Minnelli blast out the song, jubilant and hopeful – in contrast to the triumphant, almost boastful interpretation that became Frank Sinatra’s closer – in New York, New York.

Released in 1977, a year after Taxi Driver, this was Scorsese’s attempt to mount a modern take on the lavish period musical – its eye-popping production numbers undercut by a cynical realism in its depiction of a codependent romance between Robert De Niro’s short-tempered saxophonist and Liza Minnelli’s big-hearted singer. It was received with some confusion by critics and audiences who wanted something less complicated and more formulaic; I have no idea why anyone would expect an uncomplicated entertainment from the people known for Taxi Driver, Cabaret and The Godfather, Part II, but this is how MGM sold it. Maybe it’s the studio’s fault.

At any rate, it took a while for New York, New York to be rehabilitated, starting with a LaserDisc special edition of the director’s cut that restored the “Happy Endings” musical number to its climax and nudged fans to reconsider the film. I was sure the success of Damien Chazelle’s La La Land – which shifted Scorsese’s “realist studio musical” approach to contemporary Hollywood, but keeps the core of its story and its spirit – would bring it back into the spotlight, but MGM was dealing with some stuff and the opportunity sailed by.

Even now it’s considered one of Scorsese’s lesser works by people who, I’m guessing, haven’t seen it in a while. Because all you have to do is rewatch it to realize New York, New York is absolutely of a piece with the rest of Scorsese’s ’70s filmography: It’s a movie about people struggling to change, and failing, while the world rolls forward around them. (Hell, even The Last Waltz is sort of about this.) But this one has a dreamlike artifice, with Scorsese and László Kovács emulating the Golden Age musicals they grew up on – with nods to Powell and Pressburger for good measure – to create a stylized period drama with something dark rippling underneath. It’s kinda great, honestly.

Imprint’s three-disc set – packaged in Via Vision’s distinctive hardbox case, with a booklet of essays and stills – makes Blu-ray history by including the shorter European cut of the film, which runs 137 minutes, along with the 163-minute director’s cut that’s been the default edition of New York, New York since that LD boxed set. Completists will be happy to have it, and it’s certainly a tighter version of the story, but I think the extravagance of the longer version – its maximalism, its rhythms, its emotional indulgence – is essential to the effect Scorsese was chasing. Sometimes more really is more, you know?

Daniel Kremer, a frequent contributor to Imprint’s special editions, offers a new audio commentary for the director’s cut and a visual essay, “Momentary Departures: Movie Ballets, Musical Showstoppers and Detours,” about the grand Golden Age production numbers Scorsese quotes so lovingly. (Kremer also mentions the debt La La Land owes to New York, New York as well.)

Kremer’s also behind the other new featurette, “Player Piano Player: Barry Primus Returns to Scorsese’s New York,” interviewing the actor – who also turns up in Scorsese’s Boxcar Bertha and The Irishman –about his time on the production and his relationship with Scorsese. The 24-minute conversation is accompanied by an additional three minutes of material that didn’t make the cut, including Primus’ observations about the Taxi Driver script.

All of the extras produced for previous MGM editions are here: Scorsese’s introduction and audio commentary with Carrie Rickey, selected scene commentary from cinematographer Kovács, and the two-part documentary “The New York, New York Stories” and retrospective interview with Minnelli produced for the 2005 DVD. The twenty minutes of alternate takes and deleted scenes are here, along with a reconstructed alternate ending and a storyboard gallery; Via Vision has also unearthed brief press-junket interviews with Scorsese and Minnelli – yeesh – and the Super-8 version, which compresses the feature into seventeen minutes and still somehow honors the core emotional arcs.

As with the Films of Faith Scorsese boxed set, I’m stunned that Criterion didn’t beat them to it … but as with that set, Via Vision has built a world-class edition here. And they’re releasing it alongside a special edition of another, better-known Scorsese title: A 4K edition of Raging Bull, in Dolby Vision for the first time. (Criterion did get to that one first, though.)

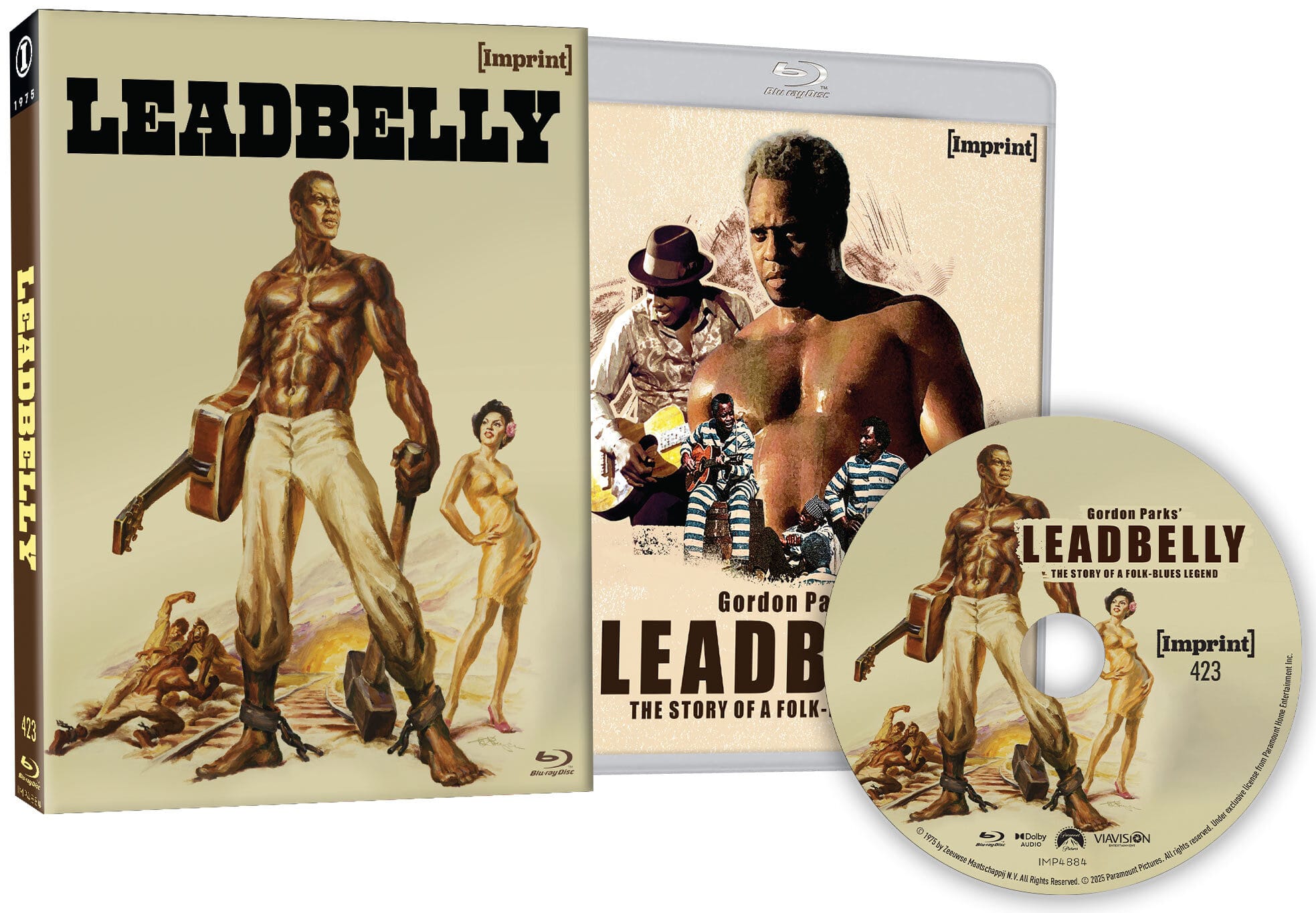

Looking for another unconventional mid-’70s studio musical? How about a period biopic directed by the legendary Gordon Parks, starring future Magnum P.I. regular Roger E. Moseley? Let’s spin up Leadbelly, a movie I didn’t even know existed until Imprint announced its release earlier this year.

That’s right: Gordon Parks, the director of The Learning Tree and Shaft, made an ambitious, decades-spanning biopic about revolutionary bluesman Huddie Ledbetter and the world in which he made his name. The film was released in 1976 and pretty much disappeared without a trace immediately afterward. Parks and producer Marc Merson accused Paramount of sabotaging the theatrical run, and at the very least it seems like the studio was negligent in positioning it as a musclebound action thing (see poster art above) instead of the more thoughtful drama it aims to be.

Ernest Kinoy’s script follows a fairly standard Great Man template, opening in 1933 as musical ethnographer John Lomax (James Brodhead) arrives at Angola Prison to record Ledbetter for his Archive of American Folk Song, laying down the essential tracks that would make Ledbetter a living legend – and lead us back through his entire life story.

We see the young Huddie get a girl in trouble at home (and also beat the snot out of a very young, very limber Ernie Hudson), flee to the big city and make a modest living playing juke joints for cash and booze until he inevitably gets into another scrap and has to move on. He meets fellow legend Blind Lemon Jefferson (Art Evans) and they play together for a while, but it doesn’t last. Nothing lasts, because Huddie doesn’t learn; he’s a great entertainer, but he’s impulsive and foolish and he likes to drink and fight as much as he likes applause.

Parks isn’t out to canonize Huddie Ledbetter as some sort of hard-done-by blues saint; every time he ends up in prison, it’s because he unambiguously did something to get there. Moseley gives the character a lot of charm, but also a sort of dullness behind his eyes: Huddie’s smile is always conditional, if that makes sense, and it falls away the moment he thinks he’s being challenged. But when he’s performing, he’s genuinely happy, and Leadbelly lives in those moments, capturing a roomful of people sharing a moment of joy and abandon. But Parks also lets us understand how rare those moments are, pausing the story to show us the prisoners and laborers trapped within the white power structure of the Jim Crow South.

Those moments – especially ones like the above image, where Huddie ends up in jail after a fight and the camera just lingers on everyone else who’s in there with him as they stare right back at the audience – make Leadbelly something more than a rote biopic, and make up for the limitations of its production. The costumes and sets don’t always convince, and the makeup on Moseley as the older Huddie isn’t great; maybe Parks didn’t have the resources he needed, or perhaps it’s just the unforgiving Eastmancolor stock of the era, but Leadbelly sometimes feels like it’s struggling. But when it gets hold of you – in its musical sequences, or in the frenzied wagon chase that opens the picture – you’ll be glad it’s back in the world.

This isn’t first time Leadbelly has resurfaced – the Criterion Channel included it in a Parks retrospective in 2021, and a DCP screened last summer at MOMA – but it is the first physical release of the title, which is genuinely startling given Paramount’s enthusiasm for the early videotape market and the general appeal of musical biopics. For comparison, Hal Ashby’s contemporaneous Woody Guthrie biopic Bound for Glory has been released on every home-video format short of 4K; I can’t imagine what the difference is there.

Obviously there were no archival extras to include, but Via Vision has commissioned two new featurettes to provide both historical and artistic context. The author and filmmaker Sheila Curran Bernard separates the man from the myth in “Leadbelly: Reclaiming Fact from Fiction,” and Daniel Kremer is here to offer “All the Decisive Moments: Folk Heroes in the Cinema of Gordon Parks,” which draws parallels between Huddie Ledbetter and the protagonists of The Learning Tree, Shaft and The Super Cops – and arguing that Leadbelly was Parks’ most ambitious project, both narratively and aesthetically.

But wait, there’s another long-absent movie to resuscitate! Imprint also brought Cliff Robertson’s J.W. Coop to Blu-ray last month, its first release on the format anywhere in the world. No extras at all on this one, but the movie certainly speaks for itself.

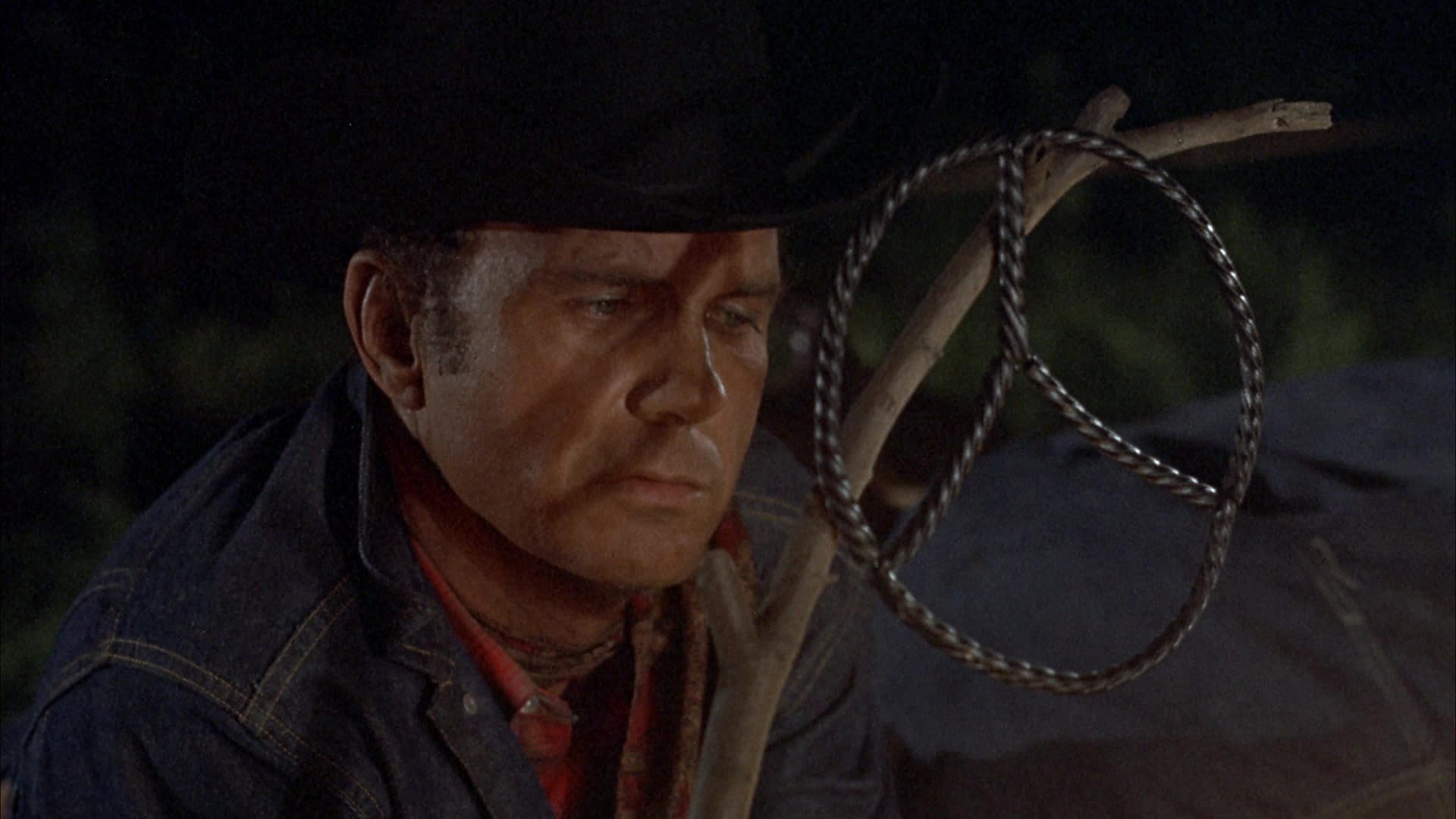

A passion project for Robertson after his Oscar win for Charly, it’s a small, gritty study of an ex-con who, after a decade in prison, sets out to reinvent himself as a rodeo cowboy – perhaps as an act of redemption, and perhaps as a way to make sense of a world he no longer understands. He picks up a young woman named Bean (Cristina Ferrare) and they follow the circuit around, earning a little money but still very much at the bottom of the ladder. If you’re curious as to where this is all going, the tag line sums it up nicely: “For J.W. Coop, second place is the same as last.”

I get the sense that Robertson – who co-wrote, co-produced and directed the film as well as playing the title role – was inspired by the way Easy Rider and Five Easy Pieces deconstructed the self-regard of American movie heroes, unpacking the posture of the biker or the drifter. His J.W. Coop is a drifter too, but not really by choice: He’s been shaped by forces like his deeply broken mother (Geraldine Page), whom we meet in an early scene that explains a lot about the way Coop relates to Bean, and how the punishment he puts himself through in the bullring might be read as almost ritualistic. The man exists to suffer, and maybe he’ll never really understand why that should be so.

Robertson is all in on his performance, to the point that any stiffness in the dialogue feels like a way to remind us that Coop is a man out of time; a decade before Eastwood made Bronco Billy, Robertson told an even sadder version of the same story – a man trying to pretend he’s decades younger and spryer, because he can’t accept a world where he isn’t. Bronco Billy had a lighter heart, but J.W. Coop genuinely pities the lost soul at its center. It may not be a buried treasure or overlooked artistic statement on quite the same level as New York, New York and Leadbelly, but it's trying to say something, and sometimes that’s enough.

Up next: Arrow takes us back to the ’80s to pick up a pint of Larry Cohen’s The Stuff, and folds time with Ole Bornedal’s Nightwatch double feature. And tomorrow's What's Worth Watching goes out to the paid tier, of course – if you're curious, you can always get a taste with the 14-day free trial!