Rediscoveries

In which Norm spins up Arrow's new editions of ALICE, SWEET ALICE, A CERTAIN KILLER and A KILLER'S KEY.

Well, you’ll never guess what. Those Criterion releases of Crossing Delancey and Drugstore Cowboy I was planning to write about don’t hit the shelves until February 18th, so writing about them this week seems kind of unfair.

Fortunately, Arrow Video has stepped up to fill the void. Let’s talk about Alice, Sweet Alice.

Alice, Sweet Alice is about as far removed from Joan Micklin Silver and Gus van Sant’s films as those landmark indies are from one another. Alfred Sole’s early slasher thriller briefly scandalized audiences with its heavily Catholic iconography, pulling on the recent success of The Exorcist – though Sole’s real inspiration was Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, soaking a knotty mystery in a giallo-adjacent aesthetic.

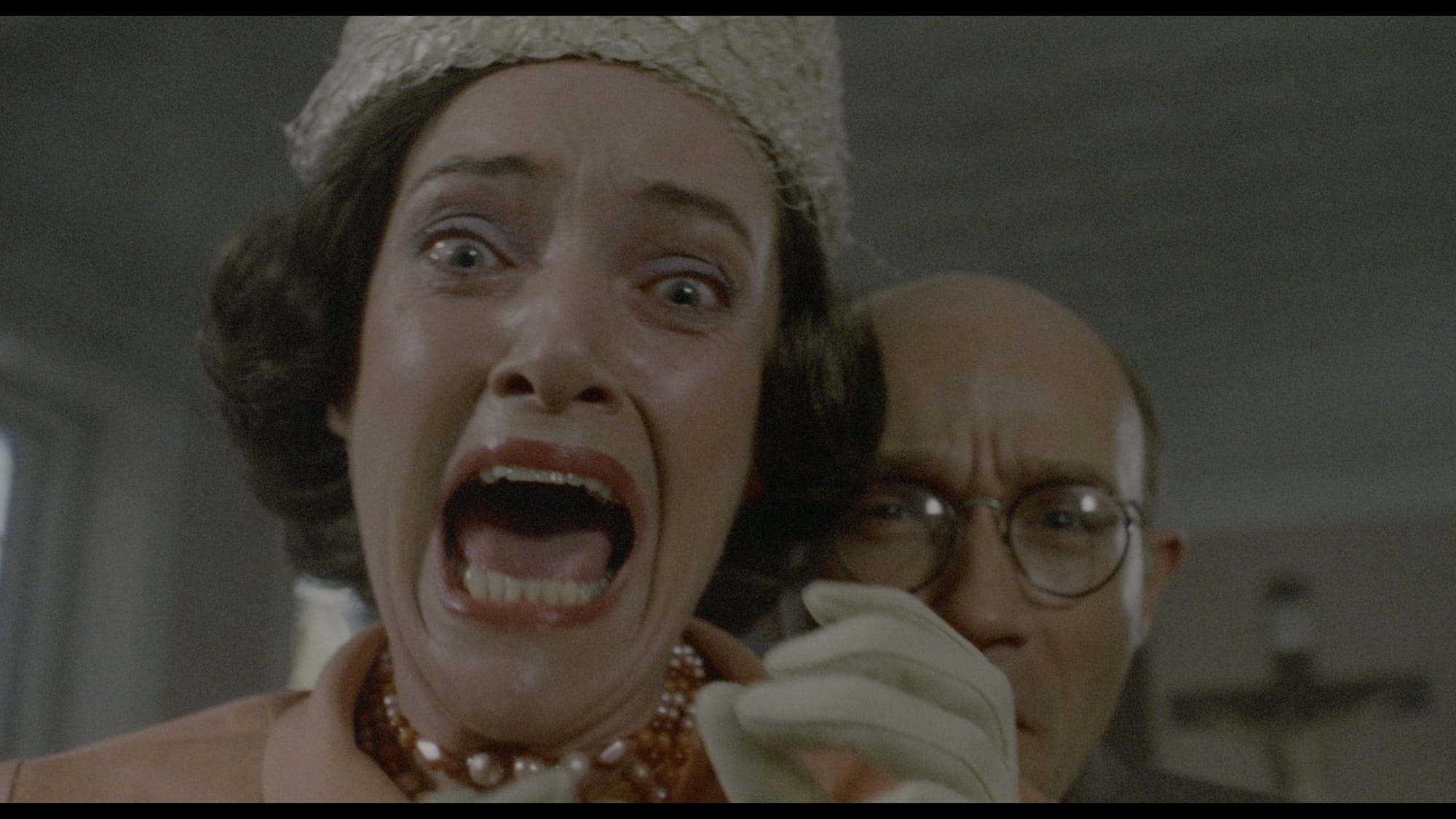

There’s a touch of the grotesque to Sole’s film that 1976 audiences weren’t ready for; in a weird way Alice, Sweet Alice feels like a project Larry Cohen might have made after God Told Me To, if he hadn’t come up with It’s Alive instead.

It’s mildly sweaty and pop-eyed, threatening to escalate into chaotic violence even in the quiet scenes, with performances just on the edge of being too big for New Jersey … but it works, much as Bob Clark’s Black Christmas works, because both films are grasping at a genre that hasn’t taken shape yet. Larry Clark’s movies always felt like they were inventing their form as they went along; Alice, Sweet Alice has the same placental sheen.

I suspect that’s far too tortured a metaphor for what the movie really is, a simple whodunit set in 1961 Paterson, where an entirely inoffensive little girl named Karen awaits her first communion … only to be strangled by someone of modest stature wearing a mask and a yellow rain slicker.

Karen was played by then-unknown child actress Brooke Shields – whose subsequent celebrity and notoriety vaulted the film back into theaters in the early ’80s – and her death is the first in a string of brutal murders, all of which have a decidedly Catholic element and which appear to center on the dead girl’s twelve-year-old sister Alice (Paula Sheppard). But is Alice the target, or the killer? The answer is a little more prosaic than it could have been, given the wild swings of the other films in this genre, but it’s satisfying just the same.

Although it was released by Warner Bros., Alice, Sweet Alice became a grindhouse staple after a copyrighting error that left it open to less scrupulous distributors; the film was also known as The Mask Murders and Holy Terror, and was released as Communion in the UK – Sole’s original title – before being caught up in the video nasty panic of the early ’80s. There have been no fewer than four different versions of the film in circulation, including a 1997 “director’s cut” released on LaserDisc that’s never appeared on any of the subsequent editions, probably because it’s one of those rare examples of a filmmaker removing material from a feature rather than expanding it.

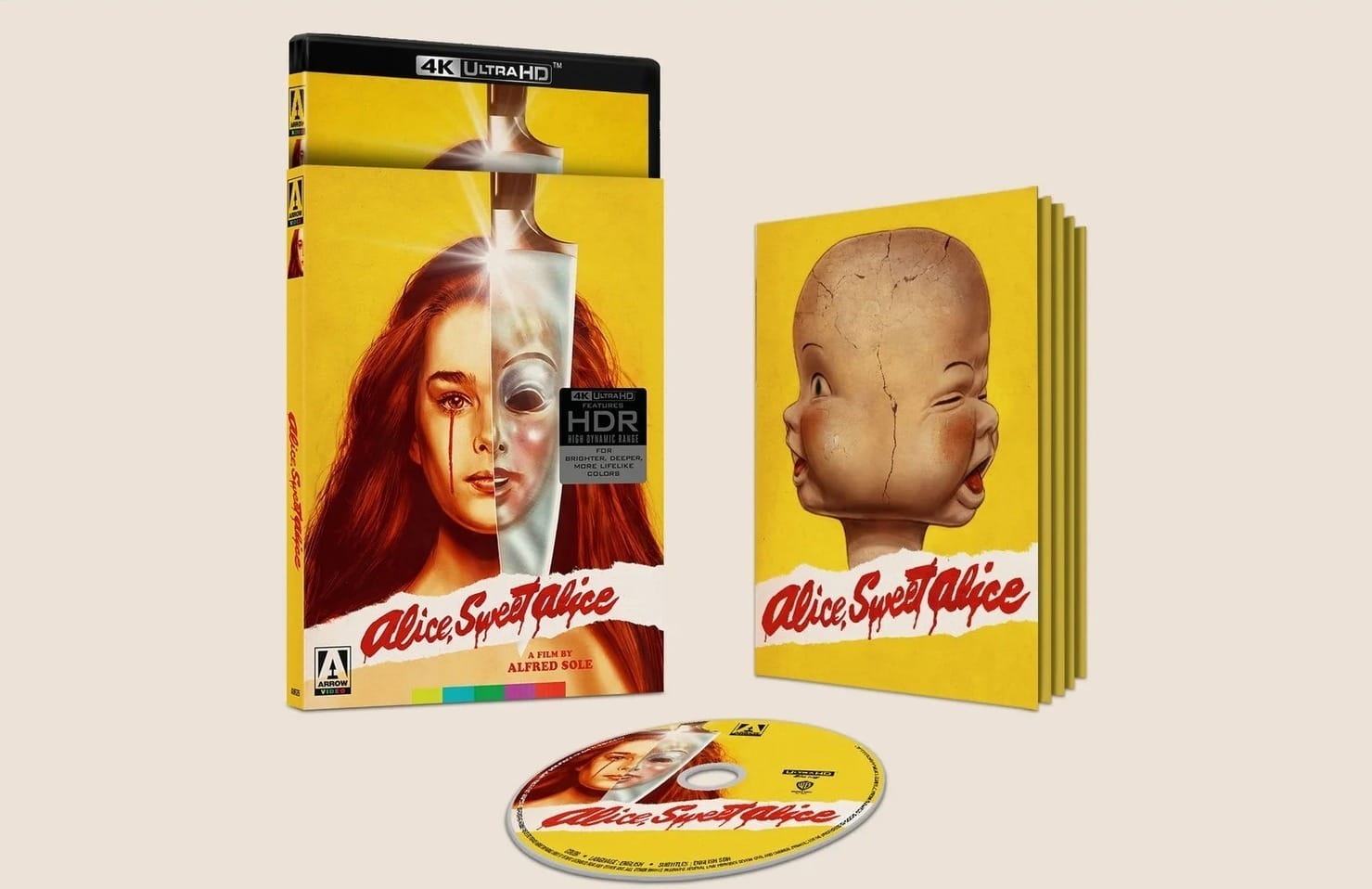

The film bounced around a little longer before Arrow Video got hold of it, releasing it on DVD, then Blu-ray and now on 4K, which offers all three of the theatrically released versions of Alice, Sweet Alice. Don’t get too worked up about it, though; Communion, Alice, Sweet Alice and Holy Terror are all essentially the same movie, and as demonstrated in the “Version Comparison” featurette the differences boil down to the credit sequences and slightly more violent shots in a couple of Communion’s murders. Regardless, all three versions look amazing, re-created with a 4K restoration of the original camera negative that honors the limitations of a low-budget production while making it look like it was shot last week.

Communion can be viewed with two audio commentaries – one with Sole and editor Edward Salier, moderated by William Lustig, that first appeared on that Roan Group LaserDisc, and an appreciation from journalist and historian Richard Harland Smith, whose authority I’ve been respecting ever since the Video Watchdog days, produced for Arrow’s 2019 Blu-ray.

The rest of the supplements are also from that Blu-ray, amounting to an hour and a half of contemporary interviews (with Sole, composer Stephen Lawrence and co-star Niles McMaster) and a pair of retrospective featurettes. Michael Gingold takes us on a cheerful tour of the film’s locations in “Lost Childhood,” while “Sweet Memories” offers a different sort of nostalgia as Sole’s cousin Dante Tomaselli discusses his connection to the film. He was five when it was shot, but was already fascinated by horror films and grew up to be a filmmaker in his own right. Neat!

Less neat is the Holy Terror trailer, which shows us exactly how gross and creepy a marketing campaign can be when it’s tied to the slut-shaming of a young woman who made this movie as an actual child. A UK TV spot for Communion is far more enthusiastic, with an excited voiceover cramming the hard sell possible into fifteen seconds of airtime that also includes a mention of the Jaws knockoff Tintorera as well, which played on the bottom half of the bill.

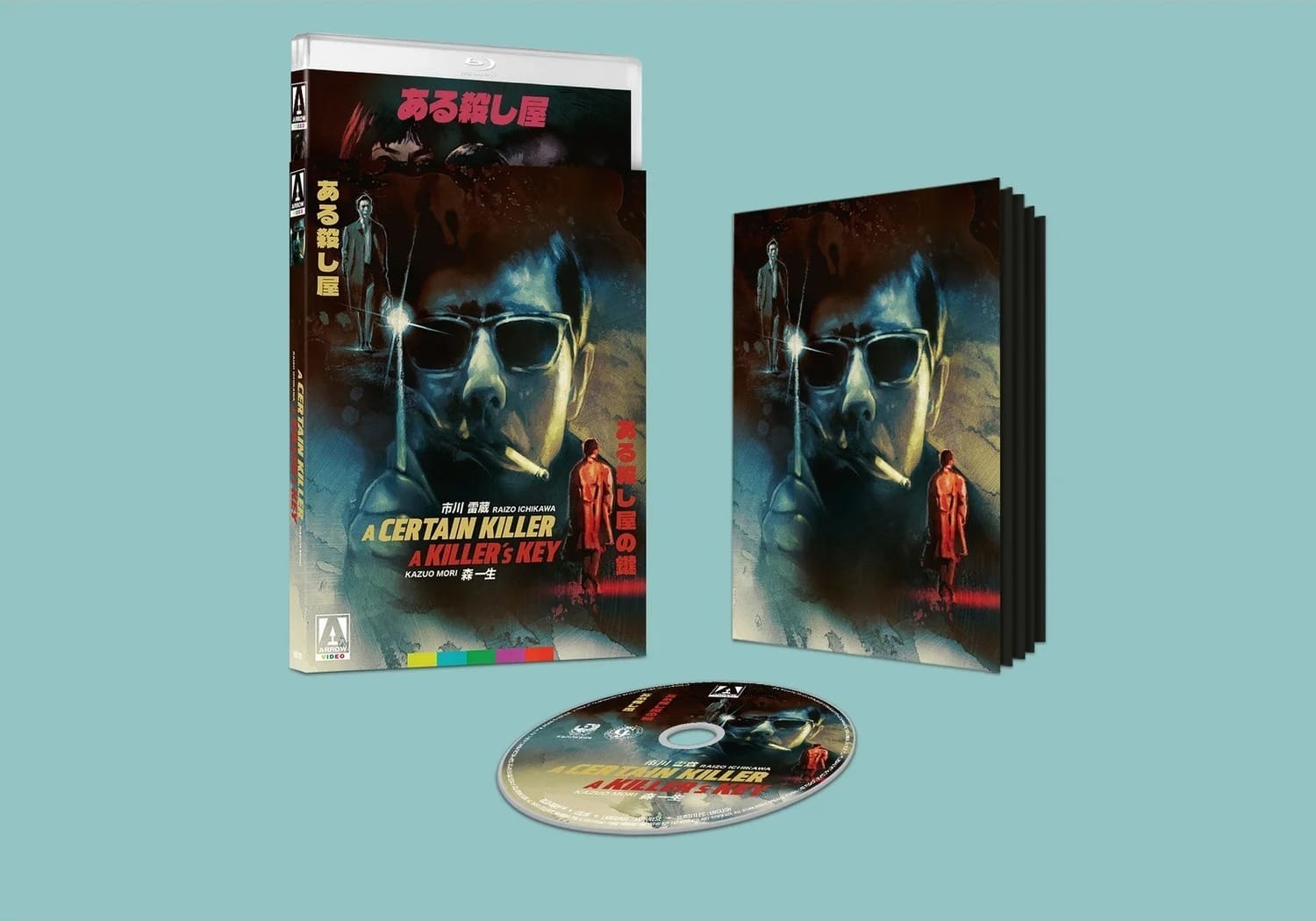

Speaking of double bills, Arrow also rolls out A Certain Killer and A Killer’s Key this week in a double-feature limited edition Blu-ray.

Never heard of them? Me neither! But I’m really enjoying Arrow’s commitment to unearthing ’50s and ’60s Japanese crime cinema, and these two films are an excellent addition to the library.

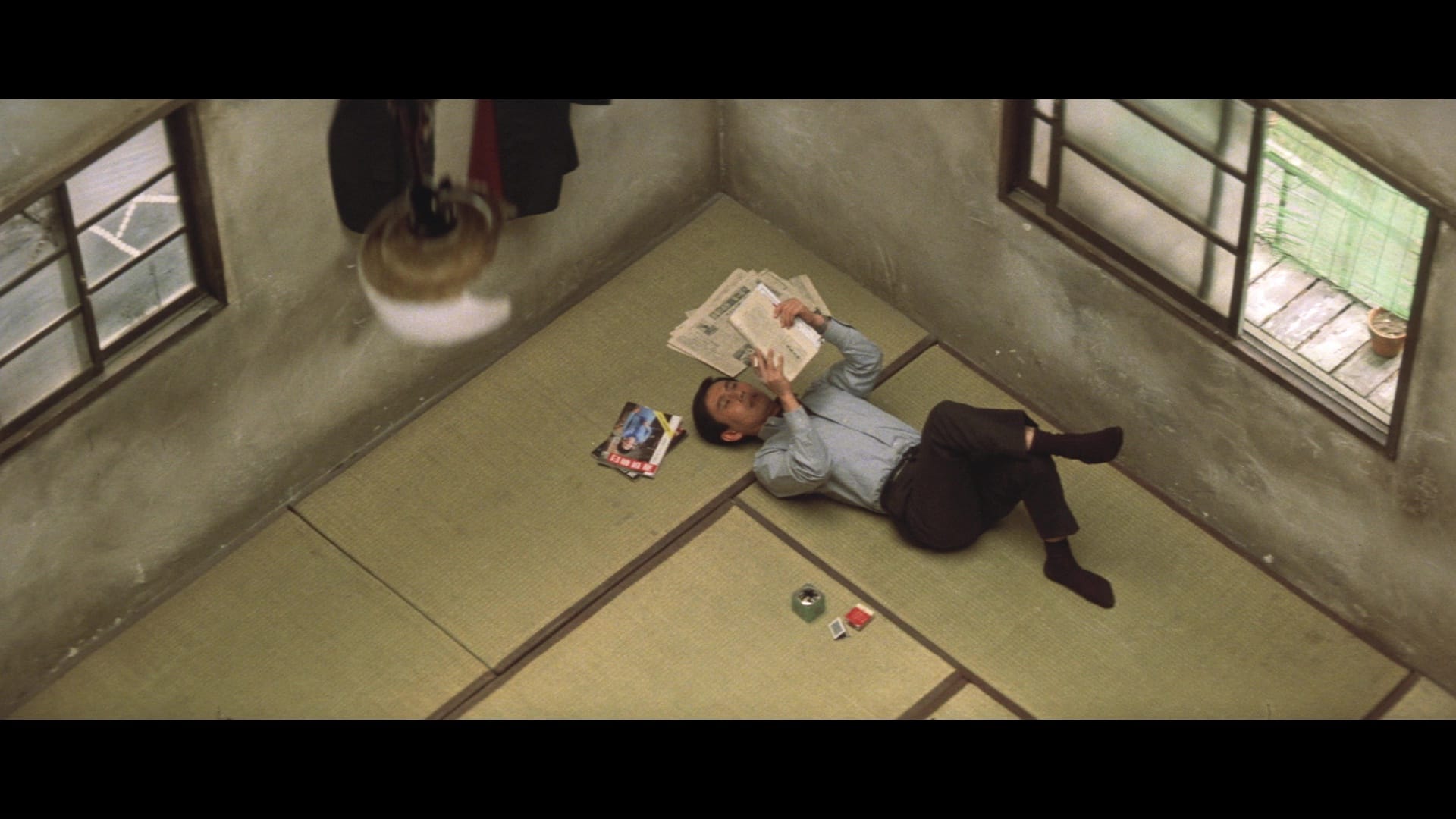

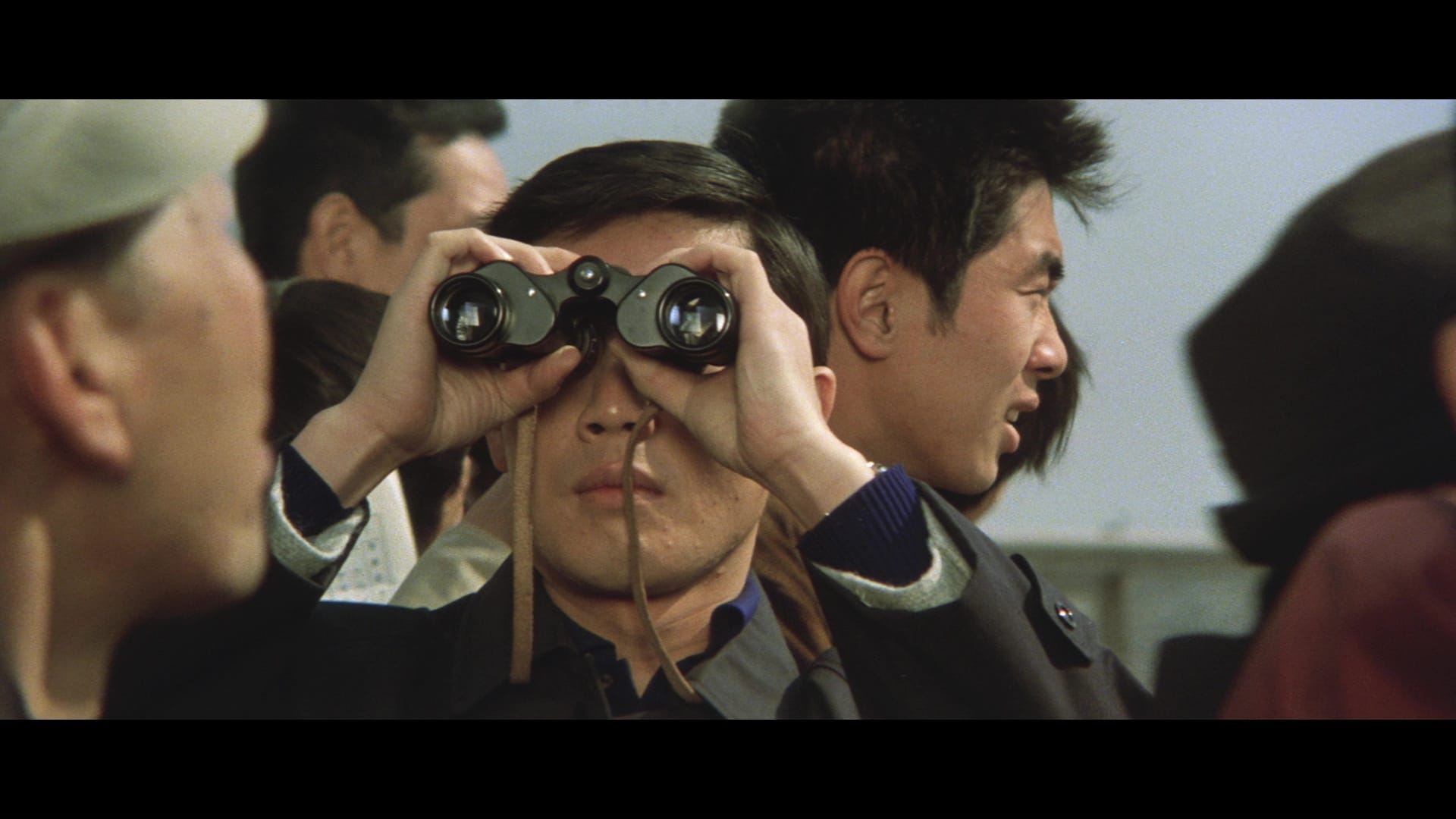

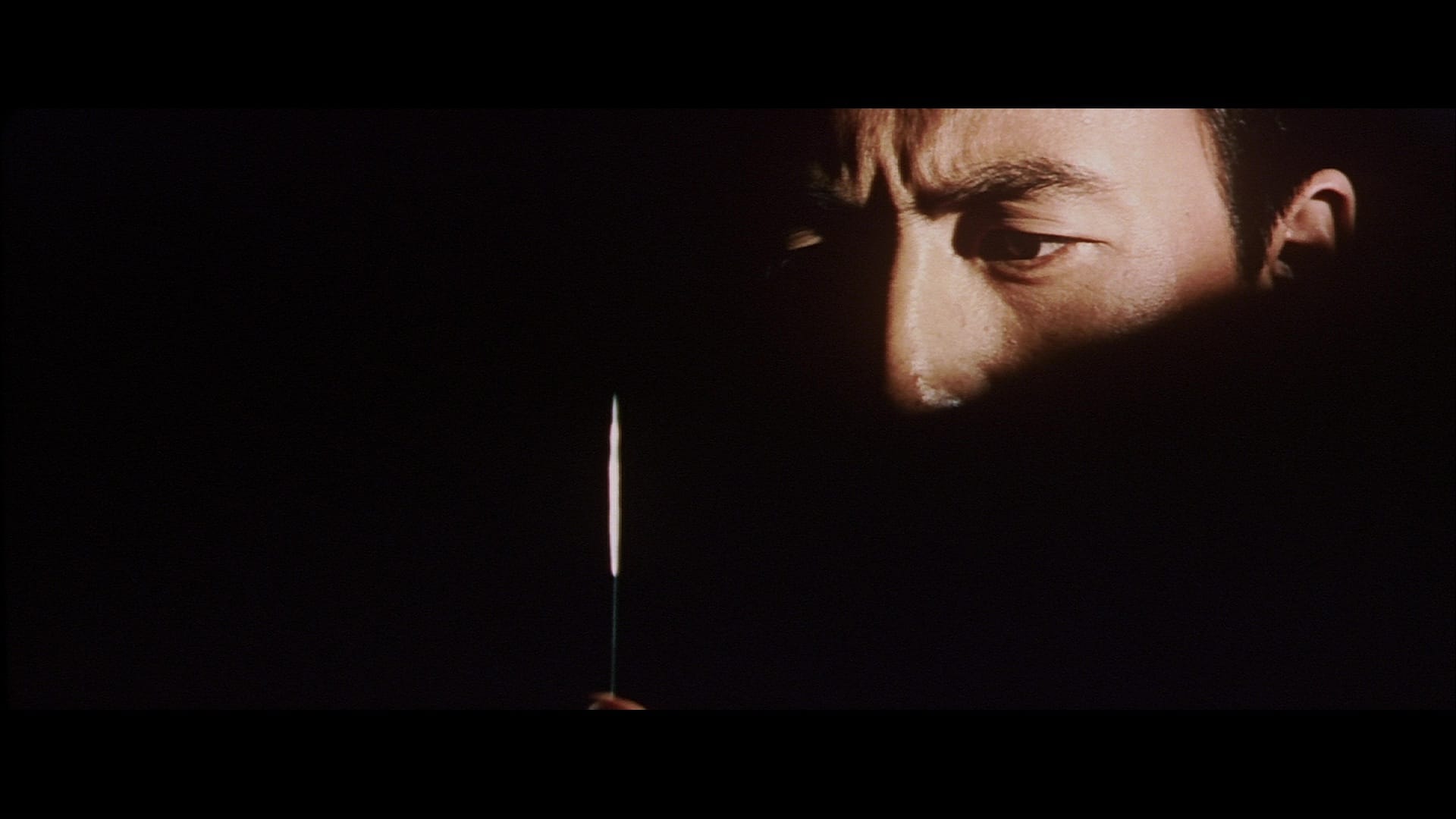

Directed back-to-back by Kazuo Mori in 1967, and using Shinji Fujiwara’s novel Zenya as their starting point, they’re pleasantly pulpy thrillers about a terse, methodical assassin named Shoizawa (Raizô Ichikawa), whose preferred method of dispatch is a needle to the back of his victim’s skull. He’s so respected that he can take contracts for two rival yakuza clans without offending anyone, and still have the time to run a pretty nice sushi restaurant as a cover. (His knife work is unparallelled!) Things are going swimmingly … until one of the clans hires Shoizawa to take out the head of the other.

Arrow’s jacket copy positions Mori’s approach as paving the way for Seijun Suzuki’s much flashier gangster thrillers Branded to Kill and Tokyo Drifter, but those films are much more invested in dazzling us with sumptuous sets and constant energy while Mori is operating in a more quotidian fashion. Suzuki’s protagonists are all about standing out and claiming space, while Shoizawa deliberately blends into the background and waits until people just stop noticing him before he strikes.

The compositions – by Kazuo Miyagawa, who shot Kurosawa’s Rashomon – are gorgeous, though.

Or possibly it’s that co-star Yumiko Nogawa is associated with Suzuki in the rear view, having just starred in the director’s Gate of Flesh, Story of a Prostitute and Carmen from Kawachi, collectively known as the Flesh Trilogy; she plays another working woman in A Certain Killer, Keiko, who gets tangled up with Shoizawa over a lunch order.

Regrettably, Keiko does not return for A Killer’s Key, which finds Shoizawa working as a dance teacher and hired for his outsider status to stop a Yakuza embezzlement case from causing a public scandal, even if it means he has to murder a whole bunch of henchmen. One might even wonder whether that’s the thing that attracts him to the job.

There’s something to these films that makes me think of Charles Willeford’s books, and how he situates his characters in largely amoral landscapes, where law enforcement is either lazy or distracted and unprofessionalism is the real crime. Willeford had only published Cockfighter when Mori made these movies, so he can’t be considered an influence, but the overall vibe is complementary. And in case you’re thinking of Elmore Leonard, Shoizawa isn’t much for talking.

Ichikawa, the star of the Sleepy Eyes of Death samurai films, gives the character a sort of consistent emptiness that pulls you in rather than repelling you: Who is this guy? Why does everyone respect him? How did he attain his elite position in the underworld? Ichikawa would be dead of liver cancer two years later, which gives his intensity a certain retroactive urgency – and makes it even sadder that he didn’t get to make more of these. Shoizawa’s a great character, and Mori could have taken him anywhere.

Arrow’s double-feature Blu-ray presents both films in solid 1080p/24, with uncompressed mono soundtracks and newly translated English subtitles; these aren’t full restorations, but they’re bright, clean transfers with minimal damage. A Killer’s Key looks a little grainier than its predecessor, but that might just be the choice of film stock.

Extras are modest but worthwhile: Audio commentaries for both films by the film critic Tony Rayns, image galleries and a half-hour featurette, “The Definite Murder”, in which film scholar Mark Roberts places the films in the context of Japan’s crime-cinema boom and makes the case that they should have been just as canonical as Suzuki’s better-known work. I do not disagree.

Up next: Crossing Delancey and Drugstore Cowboy! Trust me, they’re worth the wait.