The Artist's Way

I never got to meet David Lynch. I was supposed to interview him when Mulholland Dr. came to TIFF, but the press day was on September 11, 2001, and you know how that went. The junket was cancelled; I always figured having been there would be an ironic icebreaker when we eventually sat down for some future project. The timing never quite worked out. Now he’s gone.

There aren’t a lot of filmmakers who did what David Lynch did, for the length of time that he did it. Eraserhead turns fifty next year and remains as potent and disturbing as ever. Maybe even more so, because the decades have only deepened its sense of dread and soul-sickness. Eli Glasner at CBC asked me to define “Lynchian” in a news hit yesterday, and I found I couldn’t do it in a single sentence. It's like the old saw about pornography: You know it when you see it.

Lynch had a singular vision and held fast to it for his entire career, from his early short films straight through the Victorian steampunk nightmares of Eraserhead, The Elephant Man and Dune, to the corroded Americana of Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart and Fire Walk with Me, through the pure experimentation of Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr. and Inland Empire. That third season of Twin Peaks was a man doing whatever the hell he wanted, and it was frequently exhilarating to behold. Then there was that weird Netflix short where he yelled at a monkey and while I was not a fan I did not begrudge him for goofing around with someone else’s money. He’d earned it.

And of course smack between Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr., his two bleakest psychodramas, lies The Straight Story, a film so pure and gentle that it was initially received as some sort of prank; what the hell does David Lynch know about old farmers with bad backs? And how did he talk Disney into funding it?

But there’s the twist: The Straight Story might be Lynch’s best picture – a film that’s acutely human and bursting with compassion for people whose lives didn’t work out the way they expected, anchored by a magnificent performance from Richard Farnsworth as Lynch’s aging hero. And he is a hero, even if all he does is drive a riding mower across a couple of states. Where did that movie come from?

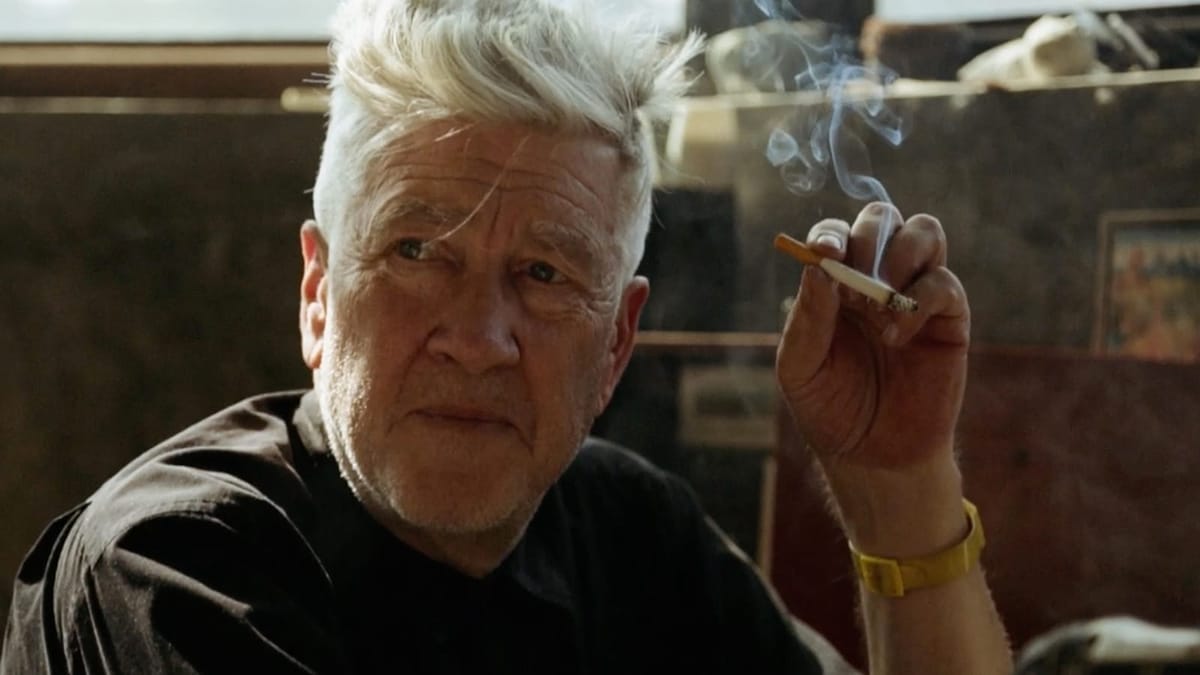

Watch David Lynch: The Art Life – it’s on Blu-ray and DVD in the Criterion Collection, and streaming on the Criterion Channel along with most of Lynch’s features – and maybe you’ll get your answer. Lynch was cagey about what his work meant – he loved not talking about his movies – but he loved to talk about art in general, and painting in particular. Jon Nguyen, Rick Barnes, and Olivia Neergaard-Holms capture him in his studio, telling stories about his formative years as a person and an artist, and leave us with a picture of a man who is fully comfortable in himself, and able to make other people comfortable as well.

I think it’s the key to the performances he pulled from his collaborators; Lynch’s signature as a director was to hold his lens on an actor until they cracked wide open, but he could only get them there by being someone they could trust with their performance, and you don’t do that by screaming or manipulation. You get there by talking and listening and understanding, in much the same way that Farnsworth’s Alvin navigates the world of The Straight Story.

That was David Lynch telling us who he was, even more so than his conversations to the camera in The Art Life or its predecessors, Lynch (one) and Lynch2. I’m sorry I never got to meet him, but I kinda feel like I did. He was right there on the screen. And he still is.