The Greatest White

In which Norm spins up Universal's glorious 50th anniversary edition of JAWS.

“You know Ellen, people don’t even know how old sharks are. If they live two, three thousand years.”

We know how old Jaws is. It’s fifty years old today, and it remains, like the behemoth at its core, a perfect machine – a bracing adventure story and rich character study, sure, but also a watershed cinematic event that’s all the more miraculous because it was entirely unintentional.

Had the shark worked, the young Steven Spielberg would still have made a great movie because he was the young Steven Spielberg, and few people have been better at doing the thing he does before or since. But the shark didn’t work, hobbling principal photography almost immediately and leading the director, screenwriter Carl Gottlieb and stars Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw and Richard Dreyfuss to reimagine their monster movie without so much of the monster.

I have a tight five about this, which Adam Schoales, Andrew Strapp and I turned into a TIFF Original a couple of years ago. But you know the deal: The shark didn’t work, and Spielberg turned its absence into the picture’s greatest strength. That hungry Great White could be anywhere, lurking below the waterline, underpinning every wide shot with excruciating tension – especially when John Williams’ score crept onto the soundtrack.

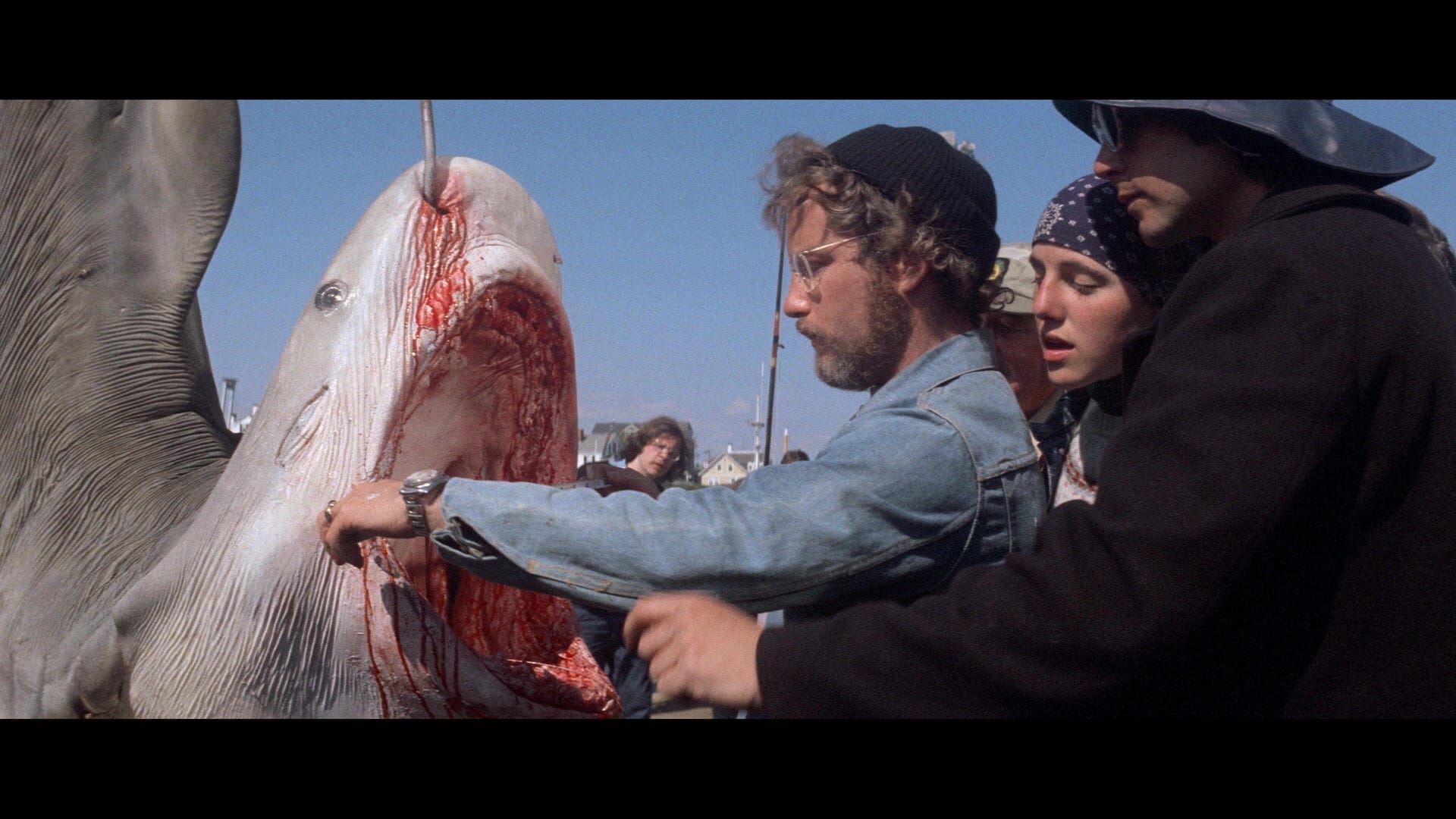

By this point, Gottlieb had already distilled Peter Benchley’s Peyton Place-ish novel about shark attacks disrupting the affairs and corruption in a small island town into a relentless thriller about an overmatched cop trying to save himself and his community from nature’s most efficient predator. But the detail that followed – fleshing out overmatched police chief Brody, enthusiastic oceanographer Hooper and grizzled sharker Quint as three different portraits of American masculinity in the post-Nixon era – is what makes the movie truly singular, infusing a simple adventure story with the emotional intelligence and understated cynicism of the New American Cinema.

The result is much more than a monster movie: It’s a complex, shifting drama about flawed, relatable people whose interpersonal dynamics add a rich layer of drama and tension to the story even before they set out to hunt a dead-eyed menace that’ll snap them in two without even blinking. That’s Jaws. It’s a perfect entertainment, a virtuoso monster movie and a film that literally changed the way movies are made and marketed.

It feels like I’ve been watching Jaws for my entire conscious life. I would have been ten when I first saw it, on a Betamax tape in my father’s apartment. He’d recorded its first network broadcast, cutting out the commercials on the fly with a chunky wired remote that had a single button. He told me and my brother that we could only watch it from 675 on the counter, which turned out to be the moment the Orca sets out to sea. Anything before that, he said, would be too scary.

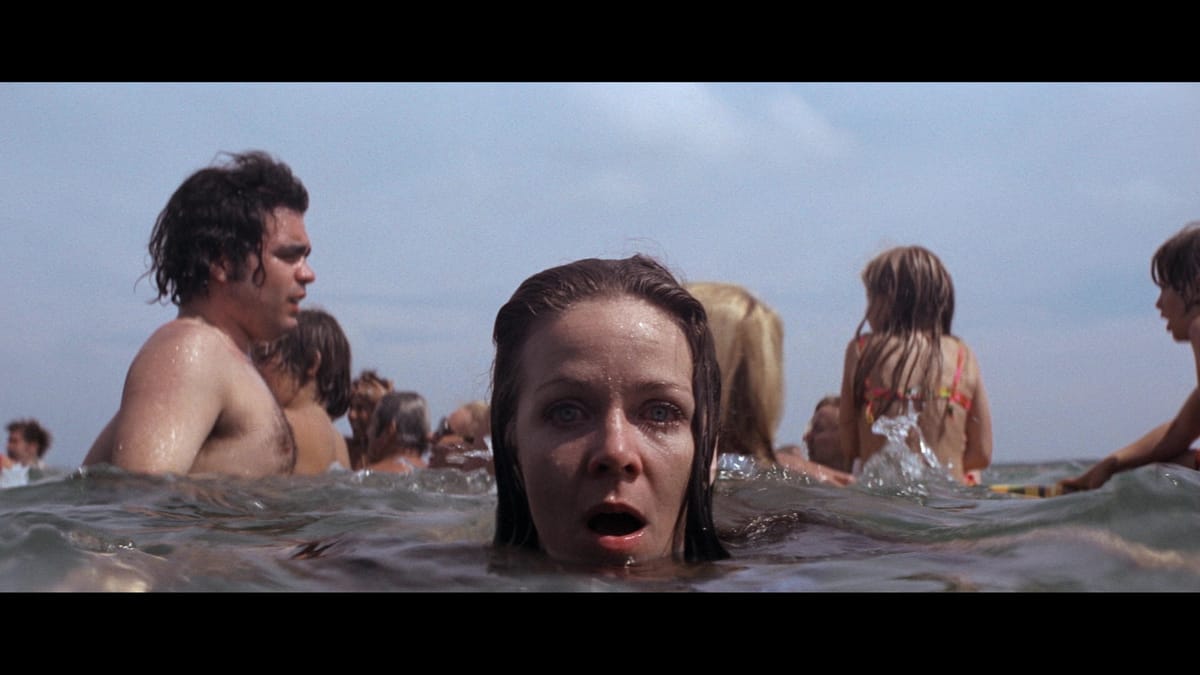

Dad was right. The first hour of Jaws has several set pieces that rank among the greatest horror moments ever committed to film, and incredibly enough ABC aired every one of them, only turning down the brightness during Chrissie Watkins’ swim to cloak Susan Backlinie in shadow. But when I finally watched to the whole movie a few years later it wasn’t the scary stuff that enthralled me, it was the story – how rich it was, how so much of it has nothing to do with the shark, and how almost none of it matters once Brody, Hooper and Quint board the Orca. It’s an exercise in paring these men down to their essential qualities and seeing how they fare against a three-ton monster that isn’t interested in the slightest about what it’s doing to Amity’s summer.

I got to discover how much Lorraine Gary and Murray Hamilton brought to that first hour as Ellen Brody and Larry Vaughn, respectively a confident, clever woman and an oleaginous glad-hander who serve as opposing spurs to Brody’s sense of duty; Ellen is perhaps the most pragmatic character in the film, making sure her husband has his zinc oxide and an extra pair of glasses as she sends him to what she’s pretty sure will be his death.

And Larry, like all great villains, doesn’t think he’s a villain at all; he’s just trying to keep the summer dollars coming in, and if he has to sacrifice a couple of lives to the monster to do that, well, he just hopes they’re not locals. He wants people to thank him for this awful, mercenary strategy. He thinks he’s doing the right thing, even to the end. Think of the scene in the hospital when Brody produces the voucher Vaughn needs to sign to hire Quint: Vaughn can’t even look at it. But he can try one last wheedle: “My kids were on that beach too.” Even then, it’s a qualified statement of support: They were on the beach, sure, but not in the water.

Back to Scheider and Shaw and Dreyfuss, and their magnificent group dynamic, which they developed in collaboration, rather than opposition, as the legend (and a certain extremely disingenuous stage play) would have it. Yes, Shaw was drinking a lot, but not so much that he couldn’t deliver one of his best performances, letting us see that Quint’s bluster is a persona forged in blood and terror, as much of a prison as the shark cage Hooper brings aboard.

Dreyfuss’ energy and emotional intelligence does tell us that Matt Hooper is a guy who’s grown up rich, though Quint’s assessment of his “city hands” reveals his own bias; Hooper’s worked plenty, he can just afford gloves. But Hooper’s bon vivant side feels like an appreciation for the nicer things he goes without on the water, when it’s just him and the boat and the fish. Dreyfuss gets that too.

And in Brody, we have our hero. A New York cop who took his family out of the city to a quiet island town where the kids can run around doing whatever, only to have to leave them all behind to fight a sea monster. Brody doesn’t like the ocean, and certainly doesn’t want to be on the Orca, but he knows if he’s not there Quint will drink himself senseless after throwing Hooper overboard, so he goes. He goes, and he keeps them from killing each other, and eventually he even enjoys himself.

This might be my favorite shot in the picture, the moment when Williams’ score shifts from scary to celebratory and we see Brody just beginning to understand what Quint and Hooper know in their bones: This is an adventure. It’s license for us to start enjoying the movie, too, to relax just enough to think these frail humans might have a chance at beating the sea monster after all. Which makes it even scarier, once it turns out the sea monster is as clever as they are. We don’t have to see a mechanical shark thrashing around to understand that; the handful of moments in which we do see the animatronic gliding through the water are plenty. It’s the way Brody reacts to it that matters, Scheider’s eyes doing the acting for both man and beast.

Christ, I love this movie.

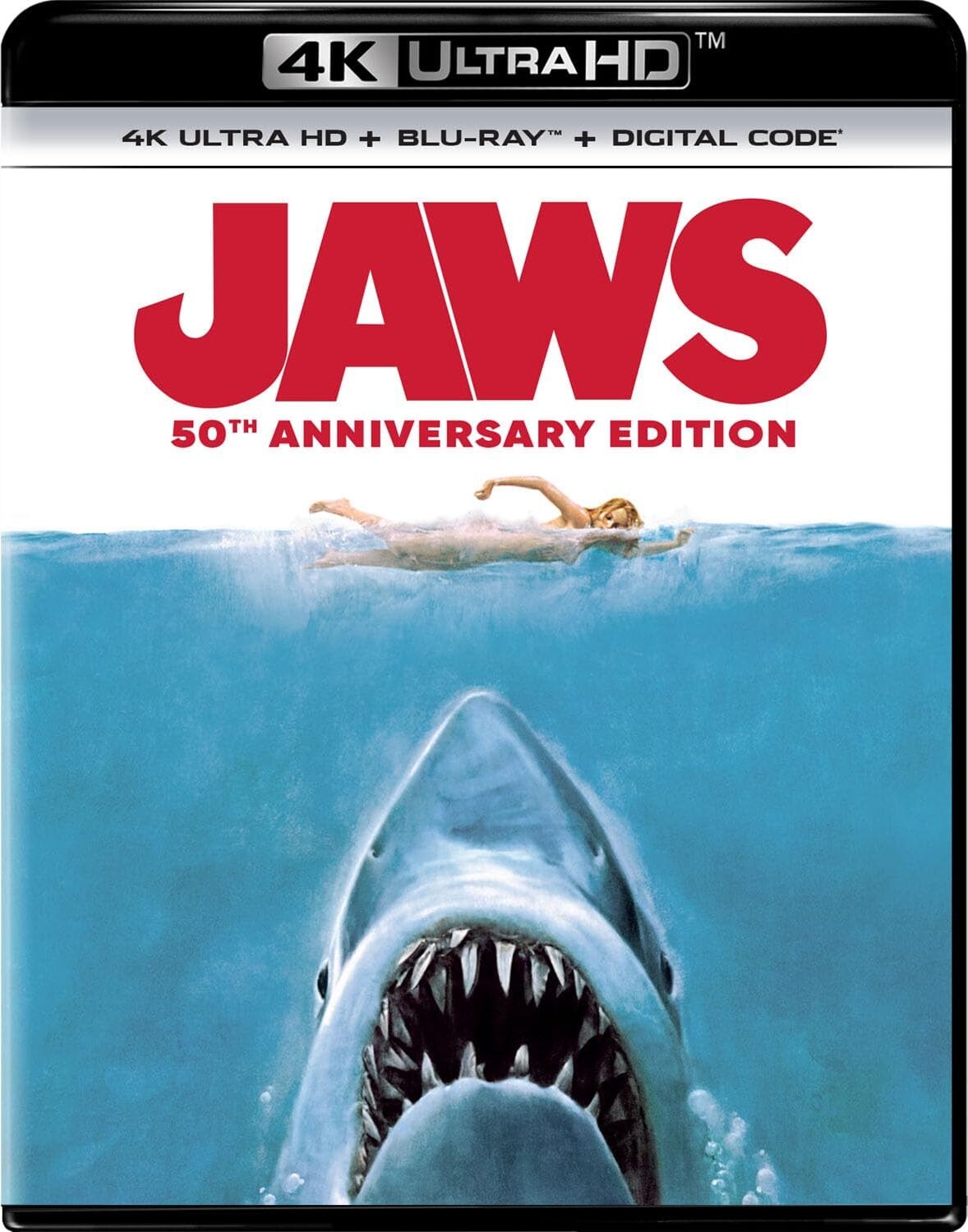

Jaws received an exemplary 4K release in the summer of 2020, with a meticulously graded Ultra High Definition master that rendered the feature as faithfully as possible to its original look and texture without going overboard: The night scenes, so crucial to this movie, were organically dark rather than carrying that extra layer of shadow that can creep into a digital feature. The only obvious HDR bump I noticed was the aura of Hooper’s tracking device blinking a little more vividly green as a barrel approaches the Orca; otherwise there’s nothing in this presentation that looks in any way contemporary. It’s 1975 in there, just as it ought to be.

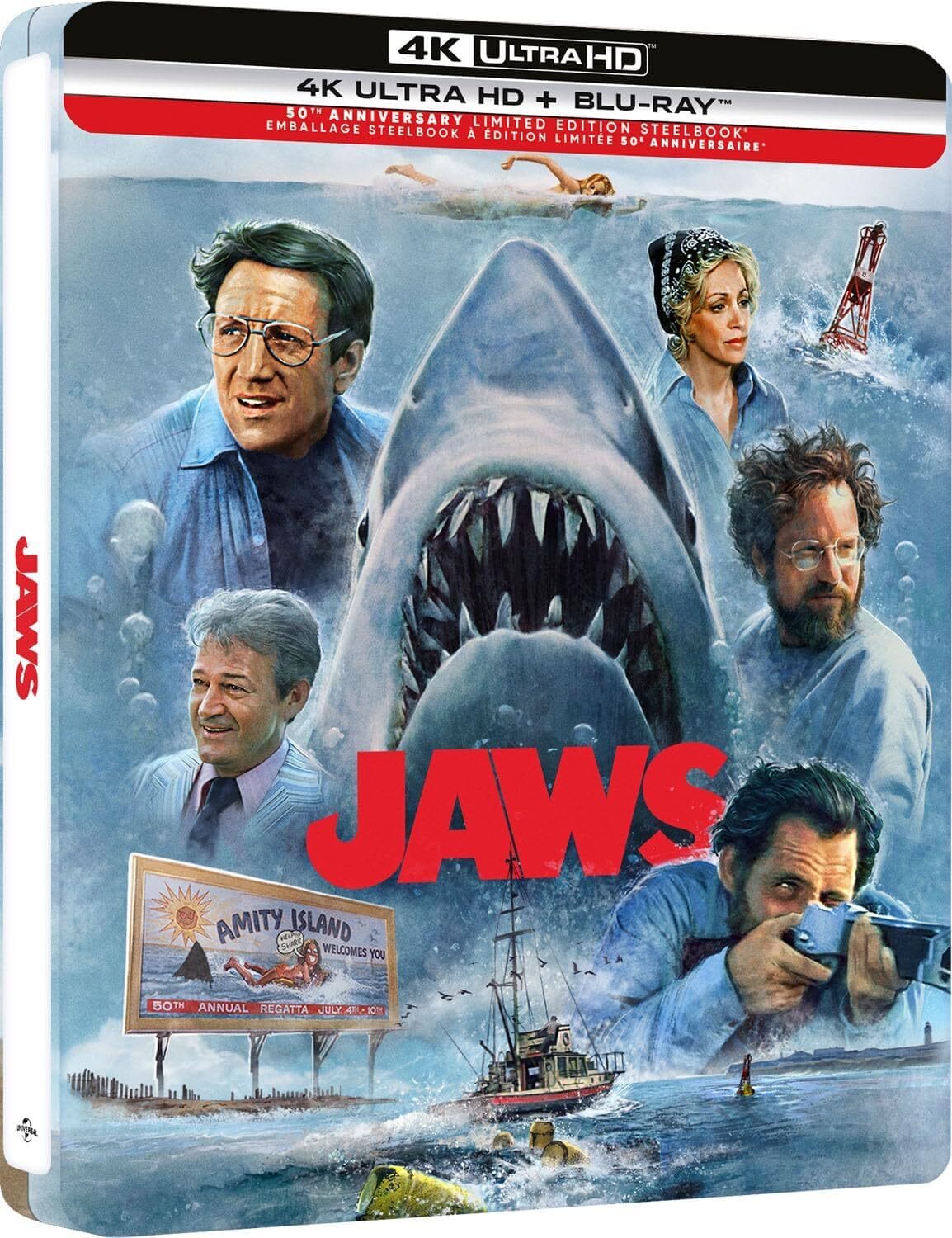

For this 50th anniversary release, Universal could have been content to simply slap the existing 2020 4K and Blu-ray discs in new steelbook packaging – and that packaging is pretty pleasing, it's true.

But we also get a bonus BD containing Bouzereau’s new feature-length documentary, Jaws @ 50 – the first new supplement in over a decade, and the first Jaws documentary that treats the film as the masterpiece it is. Where previous docs, including the one Bouzereau himself produced for the 1995 LaserDisc boxed set, The Making of Jaws, have approached the picture as a massive commercial event beloved by fans, Jaws @ 50 shifts its subject into the canon of actual cinema, balancing production stories from surviving cast and crew members (and friends of the show like George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola) with testimonials from artists whose lives were shaped by the experience of seeing the thing.

Steven Soderbergh, James Cameron, Emily Blunt, Guillermo Del Toro and Jordan Peele turn up to discuss Spielberg’s achievements in both analytical and emotional terms. Soderbergh, who’s working on a book about the shoot, opens by saying he’s seen Jaws in a theater thirty-one times; I’m sure that number has ticked up slightly since.

And Spielberg himself is here as well, sitting down for what has to be the longest interview he’s given about Jaws since that 1995 doc. At 77, he finally has the distance to talk about the film honestly; rather than softening stories of a nightmarish production with the comforting chuckle of someone who always knew things would work out just fine, he can admit he was certain the thing would destroy his career in its infancy. Instead, it gave him the world – or final cut, which is more or less the same thing to a filmmaker – and remains the best possible expression of American commercial cinema, still unchallenged after half a century. Maybe Back to the Future comes closest. Spielberg’s name is on that one too. (I would also consider Die Hard and either Get Out or Nope, and maybe The Hunt for Red October just to see if Kate is still reading this far.)

But here is the truth of it: Fifty years, three sequels and endless knockoffs later, only Jaws is Jaws. A film that thrills and entertains like no other while still very much being about something. It’s about a lot of things, really: Toxic masculinity, rapacious capitalism, mistrust of government, obsession, community, fragile human beings forced out of their comfort zones to confront a threat for which they have no training and no real understanding. It’s about Amity as a living, breathing community, and the men who set out to save it from that perfect eating machine.

But at its heart – and Jaws does have a heart – it’s about a guy who learns to love the water. He used to hate it, you know. I can’t imagine why.

The 50th anniversary edition of Jaws is now available in a 4K/Blu-ray combo edition from Universal Studios Home Entertainment, in both standard and steelbook packaging. I cannot recommend it strongly enough, but you knew that already.

Up next: Criterion conjures up new 4K editions of Sorcerer and Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould, just as Arrow brings Dark City and Swordfish to UHD. Cult classics, right?