To Tell the Truth

In which Norm spins up the new 4K releases of THE MOTHER AND THE WHORE, JO JO DANCER, YOUR LIFE IS CALLING and INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS.

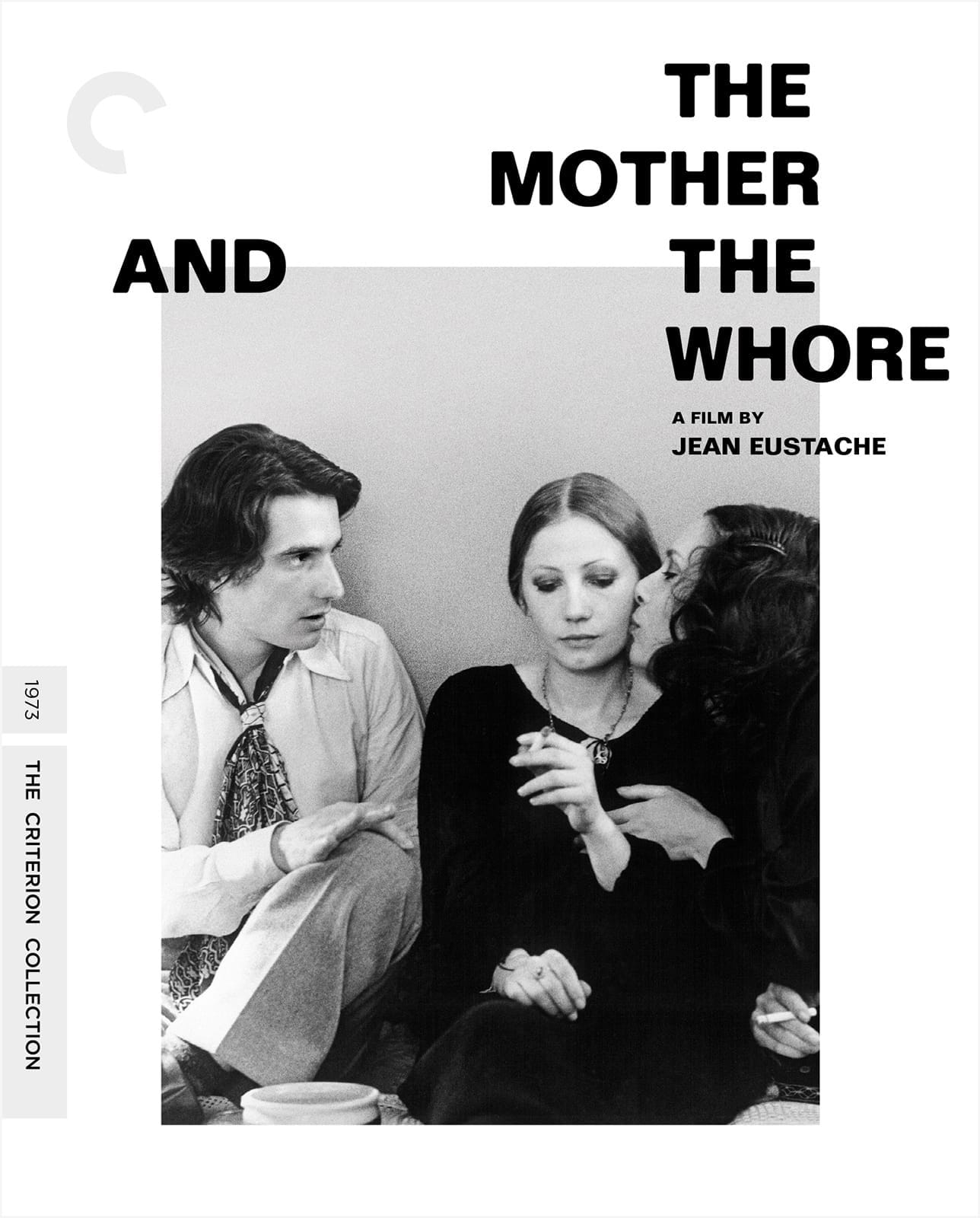

I never thought I’d see a proper North American release of The Mother and the Whore. Jean Eustache’s legendary talking picture – and I mean that quite literally – had been out of circulation for so long, its distribution rights a seemingly insurmountable tangle. I knew the film had been on Criterion’s want list since the LaserDisc days, but even when the 4K restoration arrived for its 50th anniversary I assumed it would only exist as a theatrical experience on this side of the Atlantic, drifting through rep cinemas every few months to remind audiences what they were missing.

But here we are. A bona-fide Criterion edition of The Mother and the Whore is right there on my shelf, offering the clearest presentation of Eustache’s masterpiece I’ve ever seen. One could argue that a near-pristine transfer goes against the whole vaguely shabby vibe of seeing a well-loved 35mm print at a revival house; on the other hand, this is how it looked in 1973, grubby but clean, long before it became an artifact to be pursued. You can always turn the brightness down and pretend the projector bulb needs to be changed.

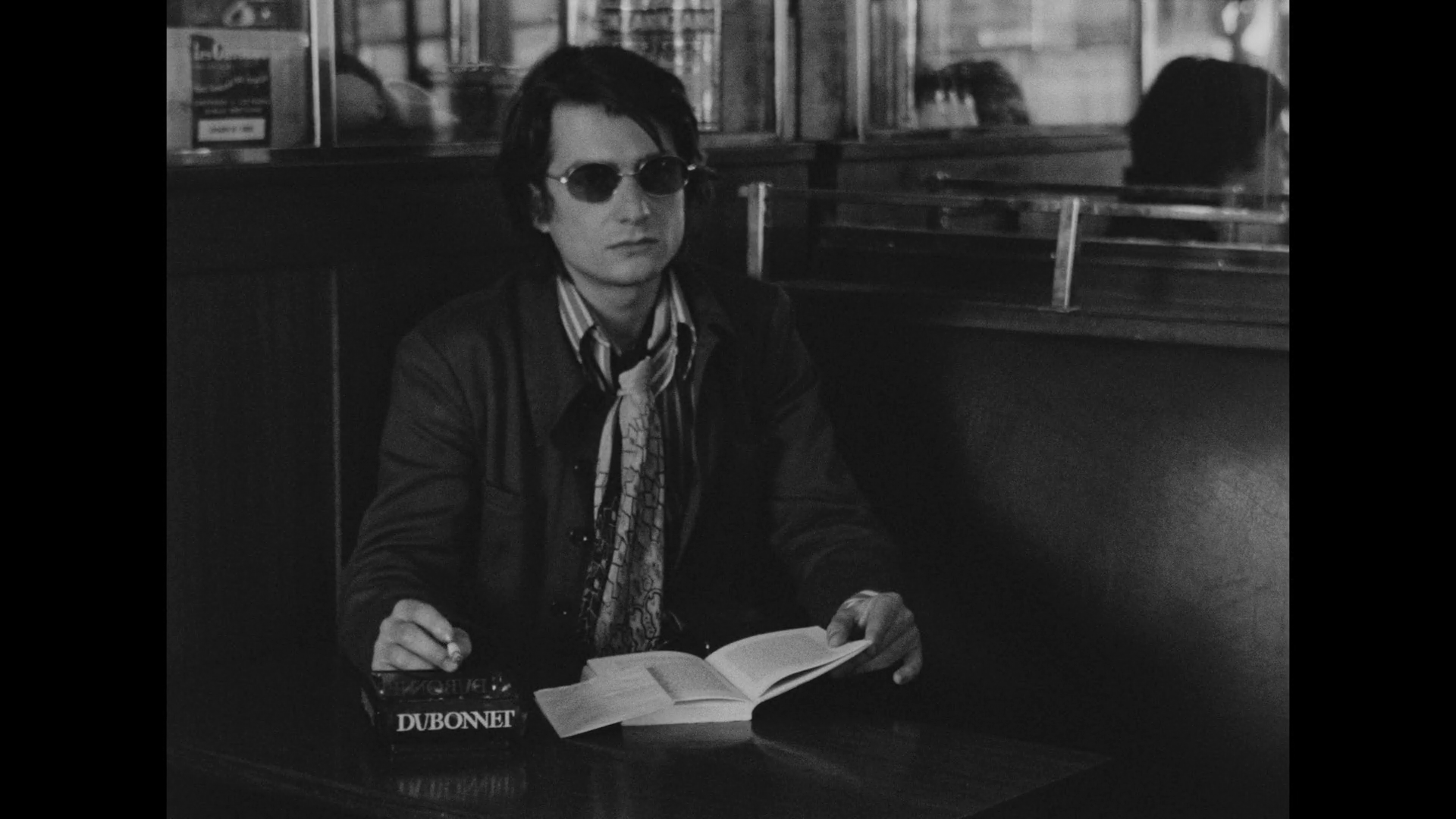

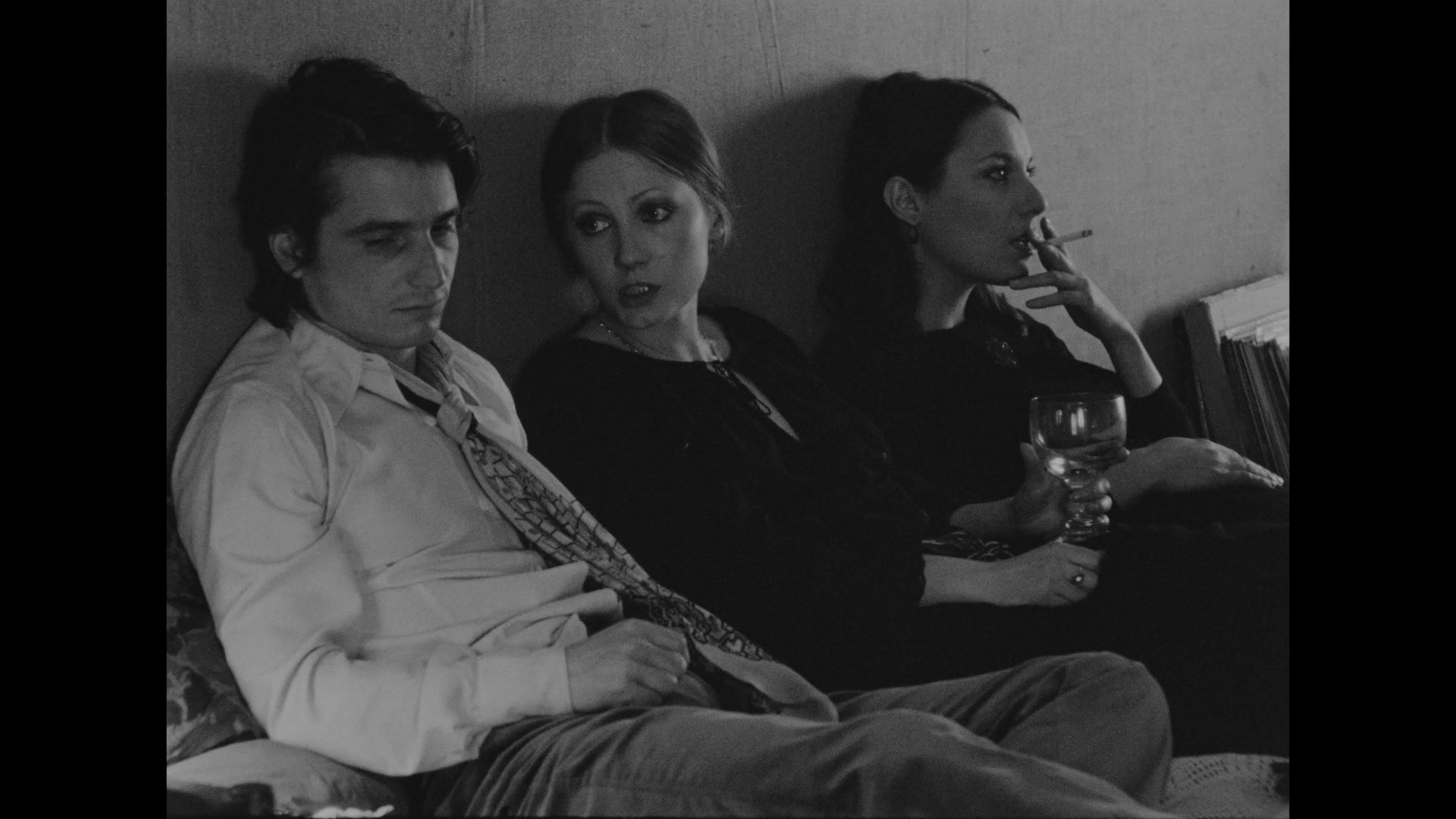

Drawn from Eustache’s own life, and shot with an almost quotidian eye for haphazardly decorated apartments and untidy cafes, the film drifts along with a young man named Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who spends his days pontificating on art and life to anyone who’ll make eye contact and his nights in the beds of various women – always going home to his endlessly patient girlfriend Marie (Bernadette Lafont) – until he meets the worldly Veronika (Françoise Lebrun) and decides he could do with a love triangle. He is a horny twerp. Things go badly.

This sounds like a pretty thin premise for a feature that runs over three and a half hours, but Eustache – making his feature debut after a series of shorts and documentaries – uses his running time to make us tire of Alexandre’s unearned confidence and unseemly self-regard. He can talk almost any woman into bed, but he’s a selfish and vaguely surly lover; a key scene finds him flummoxed to the point of hostility when he’s frustrated that a partner is distracted by her tampon.

Though he imagines himself the hero of his own story, Alexandre is the Donny Don’t of the sexual revolution; the guy with a piercing stare and a raffish demeanor that you eventually realize was your low point. Eustache spends the first two hours with this guy before shifting our focus to the far more interesting and self-aware Veronika, who is both smarter and warmer than the boy she’s indulging. It’s not much longer before Marie starts to see that too.

Eustache brings us to a similar realization, and the genius of The Mother and the Whore is that it functions as both argument and counterargument: We’re allowed to appreciate the qualities that Alexandre affects – worldliness, education, charisma, desire – and then to see the lack of depth behind the pose. He could be a pretty engaging fellow if he made an effort, but he’s discovered he doesn’t have to.

This is hardly the first French study of a stunted man, but casting Léaud – defined through his decade and a half of work with François Truffaut as a certain type of promising young Frenchman – puts a sting in the story’s tail, forcing the audience to experience Marie’s disappointment and disillusionment right alongside her. That Léaud was willing to play the part without a wink to the audience feels as daring as Eustache’s decision to make a three-and-a-half-hour condemnation of himself and the failure of French radicalism after the student revolts of May 68.

The Mother and the Whore isn’t exactly autofiction, but it’s an unblinking look at Eustache’s list of regrets, stretched out to novelistic length. Lucy Sante’s excellent booklet essay goes into considerable detail about the elements the filmmaker pulled from his own life, as well as the tragic fallout from the making of it. It was a success Eustache never had the chance to duplicate; his next feature failed to find an audience, and he spent the rest of the ’70s struggling to put another picture together. An accident in 1981 led to a deep depression; he would be dead before the year was out. But you only need to make one masterpiece to be remembered forever, and now The Mother and the Whore can be discovered by a whole new generation. I wonder how they’ll respond to it.

Criterion’s release offers a solid supplemental package, starting with a new interview with co-star Lebrun – who’d been in a relationship with Eustache years before he cast her as Veronika – and a conversation between author Rachel Kushner and the director and academic Jean-Pierre Gorin about the cultural environment from which The Mother and the Whore emerged. There’s also a featurette about the film’s restoration, and an archival episode of the French TV series Pour Le Cinema in which Eustache and his cast discuss the film at Cannes. All of it is riveting, honestly.

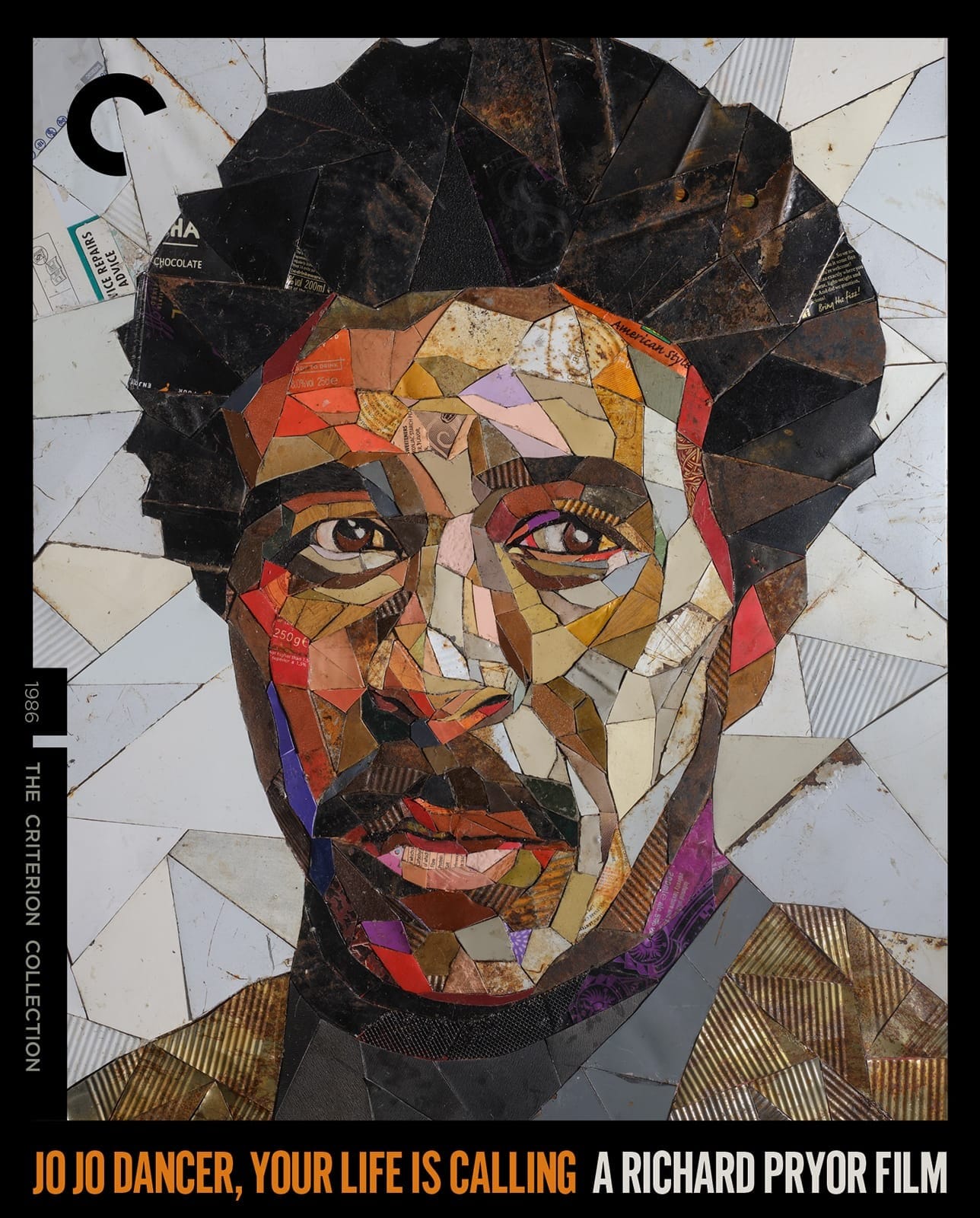

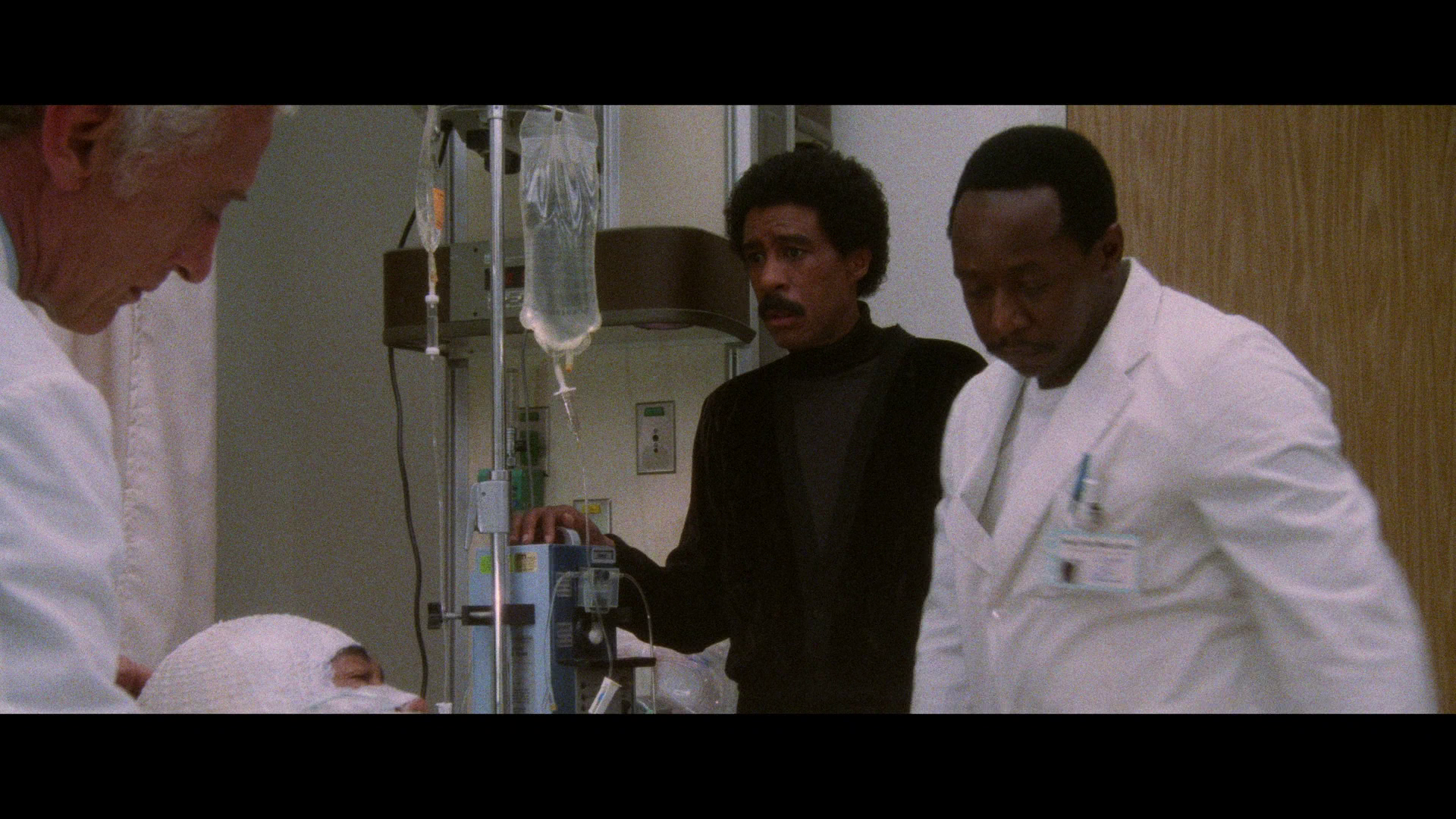

If Eustache’s film was the only title Criterion was reintroducing into the culture this month, that’d still be a major accomplishment. But there’s another deeply personal, painfully excoriating work arriving alongside it, and one nobody saw coming: Richard Pryor’s Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling.

Made six years after Pryor nearly died in a fire that was either the result of an accident while freebasing cocaine or an attempted self-immolation, it’s also a nakedly autobiographical drama about a man who has failed to live up to his own potential, and instead embraced a toxic form of self-indulgence. “Jo Jo Dancer” is a hugely successful comedian, fearless and wildly funny, maybe even the voice of a generation. But none of that matters, because his life is spent in service to his drug addiction, which might once have been a form of self-medication but now owns him fully. Cocaine is squeezing the life out of him, and he knows it – but he can’t stop. And maybe he doesn’t want to.

Jo Jo Dancer is the only movie Pryor directed, maybe because he had to. (He also produced it, and wrote the script with Rocco Urbisci and Paul Mooney.) Opening on the day of the fire, which sends Jo Jo flashing back through his life as he lies in a hospital bed, it’s Pryor’s version of All That Jazz, with an additional meta element that Bob Fosse would surely have killed to have thought of first: The adult Jo Jo is present in the flashbacks, a ghost gloomily haunting himself as a child, a struggling young performer and even his present-day self, making wisecracks that no one can hear.

It makes perfect sense now, but in 1986 it was roundly rejected. Critics and audiences didn’t know what to do with it. Hadn’t Pryor just talked about the experience in Live on the Sunset Strip? Superman III didn’t work out, but couldn’t he be happy making more silly comedies with Gene Wilder? But Pryor wasn’t ready to move on, and in Jo Jo Dancer he gave himself the catharsis he needed. It’s honest and painful, and even pretty funny … and if it sometimes threatens to spin out of control, as in a sequence where Jo Jo’s standup is drowned out by Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Goin’ On” on the soundtrack, that feels true to the experience inside Jo Jo’s head.

And while there could have been more time spent on the women in Jo Jo’s life – especially Debbie Allen’s self-possessed Michelle – their brief appearances in the film seem appropriate to Jo Jo’s hazy, clouded memory. He was too drunk or high to really appreciate them when they were there. (Or maybe their scenes were cut for time. Either way, it works.)

I hadn’t seen Jo Jo Dancer since the ’80s, because it’s been fairly difficult to find – its only DVD release was back in the flipper days, when you got the widescreen version on one side and the full-frame version on the other – so Criterion’s 4K edition was a revelation. It looks brand new, with a detail that underscores how personal the project is for Pryor: Even in the flashbacks, the burn scars on his face and body are clearly visible. It’s impossible not to think about what he must be feeling in every moment, how painful it must have been to write this thing and then go out and make it. But he did it. It’s here.

Pryor himself has been gone for 20 years now – and his health issues meant his last screen performance was eight years before that, in David Lynch’s Lost Highway. But Criterion’s special edition conjures him in a 1985 appearance of The Dick Cavett Show, talking about the movie, his career and his life for the entire episode. And Robert Townsend gives both Pryor and Jo Jo Dancer their due in a new featurette. He’s a fan, and a student. It’s a good piece.

Finally this week, there’s Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, roaring back into print in new 4K and Blu-ray limited editions from Arrow Video just ahead of Lionsgate’s much-anticipated 4K restorations of Jackie Brown and the Kill Bill films.

I remain ambivalent about Basterds, which feels like it marks a turning point in Tarantino’s career, where the failure of Grindhouse led producer Harvey Weinstein to double down on re-establishing his golden goose’s artistic bona fides by tackling a historically significant subject, and Tarantino’s grandiosity led him to rewrite World War II.

I don’t say this to minimize Christoph Waltz’ silken depravity as chatterbox Nazi Hans Landa, or Mélanie Laurent’s boiling rage as Shoshanna, the woman who escapes him and plots an elaborate revenge, or Brad Pitt’s square-jawed pragmatism as Aldo Raine, the leader of an American squad of Jewish GIs (among them B.J. Novak, Samm Levine and a bulked-up Eli Roth), on a mission to assassinate Hitler at a gala screening of a German propaganda film. They’re all doing excellent work – as is pretty much everyone in the picture, really.

But the various stories take forever to intersect, and there are additional subplots – one involving Daniel Brühl as the German war hero who grows increasingly uncomfortable with his role in that propaganda project, and another with Michael Fassbender as a British spy who plays a brief and disastrous role in that assassination plot – that let Tarantino indulge himself in digressions and conversations that slow the pace without contributing anything to the package.

Sure, we get to see Rod Taylor as Churchill and Mike Myers as a British general, but those scenes are about as useful to the plot as the bit in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood where Brad Pitt beats up Bruce Lee.

Still, I acknowledge that people love this movie way more than I do, and if you’re a Tarantino completist of course you’ll want to upgrade your copy from Universal’s earlier UHD release to Arrow’s spiffy new edition, which comes packaged with a collectible book of new essays from Dennis Cozzalio and Bill Ryan and silly stuff like a commemorative booklet from the (fictional) Nation’s Pride premiere, a beer mat from La Louisianne and a recipe for strudel.

In addition to the comprehensive supplemental package produced for the original Universal Blu-ray, Arrow’s also commissioned some impressive new extras – interviews with co-star Omar Doom, makeup effects wizard Greg Nicotero and editor Fred Raskin (“What Would Sally Do?”, in which he speaks lovingly and sadly of his mentor Sally Menke, who died far too young in 2010), new visual essays from Walter Chaw and Pamela Hutchinson and a discussion of Nazi-era French cinema with Christine Leteux. It’s as comprehensive as anyone could want; I just wish I liked the movie more.

The Mother and the Whore and Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling are available in 4K/Blu-ray combo and Blu-ray-only editions from the Criterion Collection. Inglourious Basterds is available in separate 4K and Blu-ray editions from Arrow Video.

Up next: This month’s new releases include Smile 2, Venom: The Last Dance and Heretic. Will any of them arrive in time for me to write about them? Let’s find out together.