Working Men

In which Norm celebrates Criterion's resurrections of SORCERER and THIRTY TWO SHORT FILMS ABOUT GLENN GOULD.

William Friedkin’s Sorcerer is one of those movies that’s faded in and out over the decades. Released in the summer of 1977, it was so poorly received by audiences that theater owners were more than happy to swap it out for more Star Wars after its first week. And in fairness, I get it: Where Star Wars delivered exactly what it promised, which was wars in the stars, Sorcerer was a moody, grimy remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 The Wages of Fear, a thriller about four exiles in a Latin American village who agree to drive trucks filled with nitroglycerin through the mountains to snuff out an oil-rig fire. There are no sorcerers in the film.

Somehow “Roy Scheider drives a truck filled with explosives” wasn’t a good enough hook for the ad campaign, which went hard on See The New Film From The Director Of The Exorcist! – and instantly made the title feel like a bait-and-switch. Just calling it Wages of Fear would have gotten hipper audiences on side, at least. Roger Corman would have called it Nitro Truckers, and put it in every drive-in in America. It would have made its money back, at least.

But no, Friedkin stuck with Sorcerer, and people rejected the nitro truckers. Reviews were mixed, too, and the picture was dismissed as a failure. Except, of course, that it’s not.

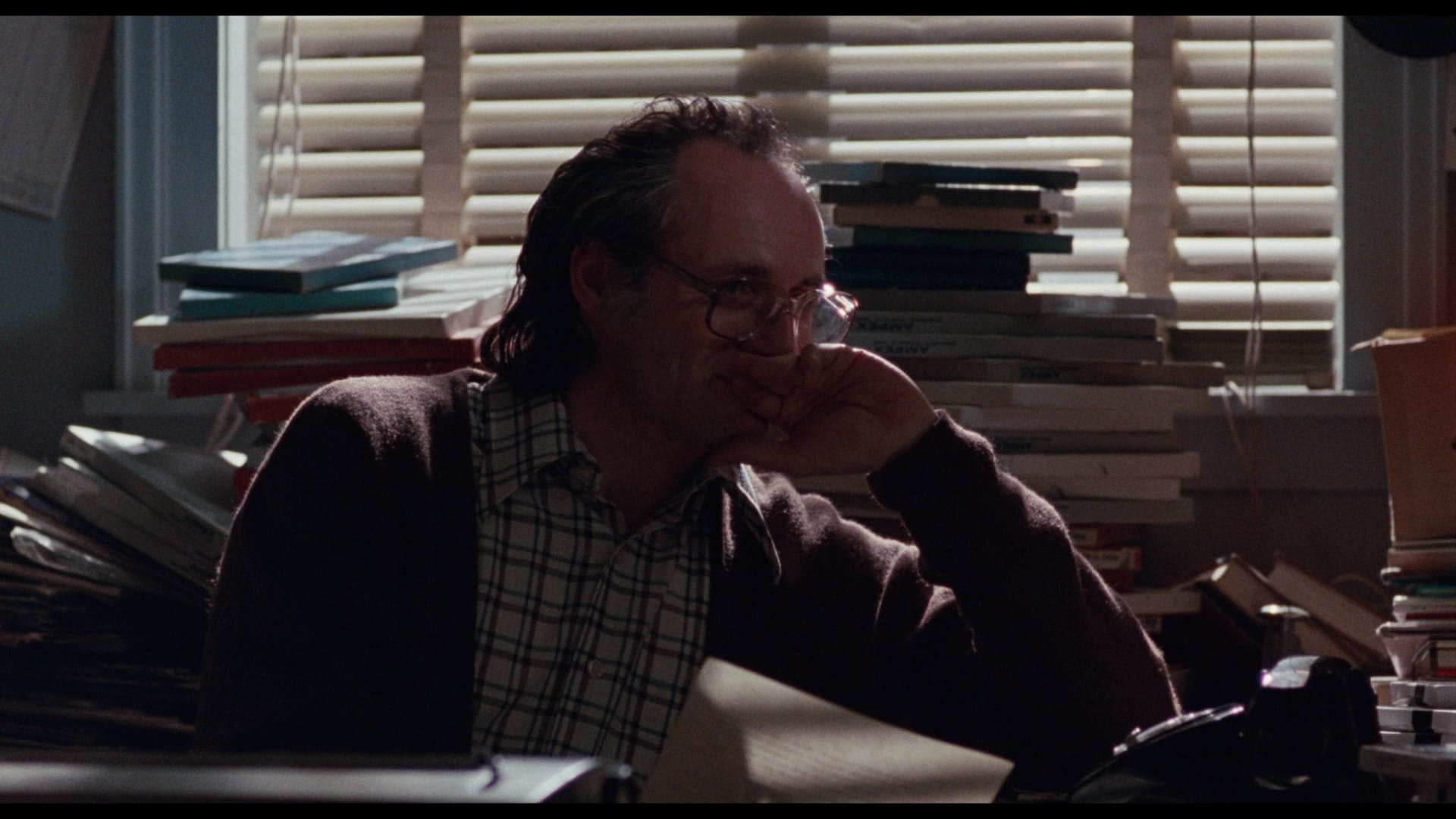

Sorcerer might not be universally acclaimed, but I’ve loved it since I saw it in a half-empty rep theater sometime in the late ’80s. (I think it was the Bloor; I remember the experience as literally overwhelming.) Friedkin may have taken pains to avoid directly aping Clouzot’s film – though how many ways are there to shoot men in trucks, really? – his adaptation shares the same burly clarity and intensity of focus as its predecessor. Friedkin brings his fascination with documentary-style realism, immersing us in the sun-blasted, sweat-soaked misery of his unnamed police state long before his protagonists head into the jungle. And once they get there, in the torrential rain and the thickening foliage, the jungle itself seems determined to thwart their mission – unless it’s begging them to abandon it.

That was the idea at the back of my mind on this viewing, my first since Friedkin released his restored edition in 2014: Were we all wrong? What if the jungle isn’t hell, judging these strangers for the bad acts we saw them commit in the film’s prologue? What if it’s their last warning? All the violence in the film is within the context of civilization; robberies, murders, embezzlements, betrayals. The moment the two trucks get underway, all of that vanishes and Sorcerer becomes even more stripped down.

It’s men driving against the elements, relying only on their bravery and their reflexes. Who they were doesn’t matter any longer. What they did happened in another life. They aren’t even traveling under their real names by the time they meet, and even their trucks – ancient machines running on salvaged parts – are barely recognizable as the original vehicles. Maybe the obstacles placed in their way are warnings, not obstructions. Get out, walk away, start again.

I don’t think this appears anywhere in the text, which is heavy with doom and despair from the very first. The kindness in Scheider’s eyes draws us in, but there’s plenty of darkness in his heart. We aren’t given the same opportunities to connect with his traveling companions: As a hitman, a weasel and a terrorist, respectively, Franciso Rabal, Bruno Cremer and Amidou are all clearly shitty people, and knowing their histories means we get to wonder whether they’ll turn on Scheider, or each other, when things get rough. Get out. Walk away. Start again. But of course this isn’t that kind of story.

If you want to bring that subtext into your viewing of Sorcerer, be my guest. But I won’t be offended if you shake your head and watch it without my weird little idea, plunging into Friedkin’s determination to make the experience as real as possible even as he slides us into a hallucinatory dream state – as if we’d been awake for three straight days alongside these men, watching their world transform into something unknowable. What Friedkin accomplished in Sorcerer is frankly stunning, amping up Clouzot’s nerve-shredding tension with a layer of tactile, physical presence: Everything we see is real, after all.

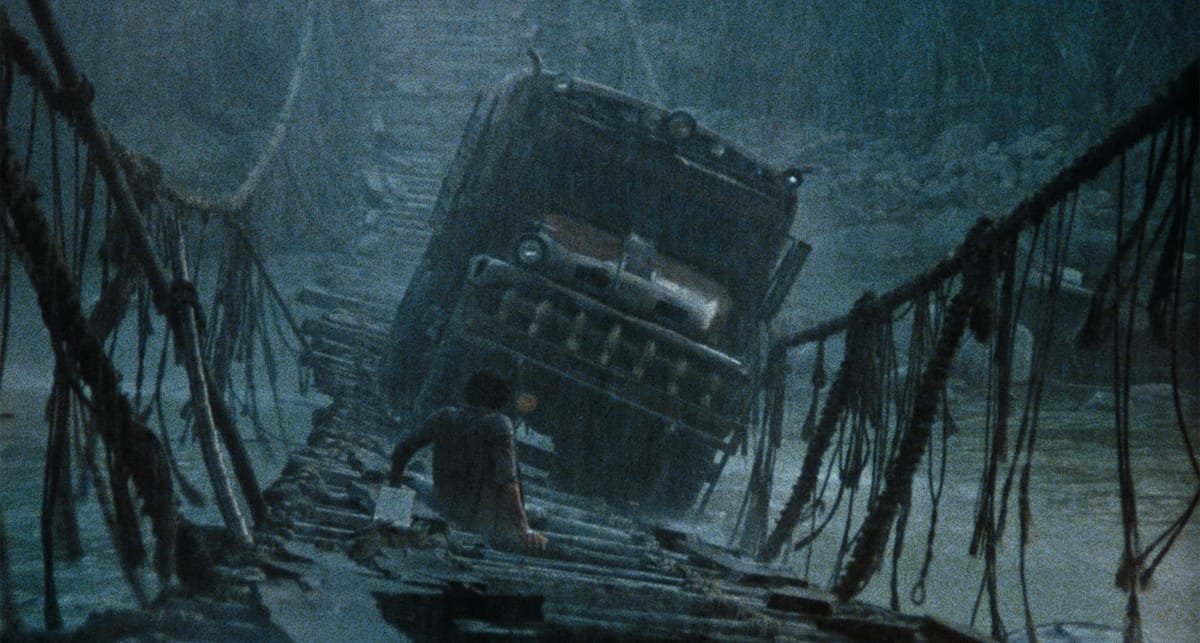

An oil well explodes into flames shockingly close to the camera, a rioting crowd seems seconds away from tipping into chaos, that truck swaying on the rope bridge is really a truck swaying on a rope bridge. Presumably, it was all engineered to guarantee everyone’s safety – those are extras, not rioters, the oil rig must be a pyro effect, that truck is secured by cables we can’t see. This was a big studio production, after all. But Friedkin knows exactly how to play those images to make us feel unsafe, or at least queasy with tension. There’s a reason even the still image of the bridge crossing is so powerful: A truck shouldn’t do that. Something is wrong here. The wrongness is the point.

Criterion’s new 4K edition of Sorcerer is a work of art in itself, honoring Friedkin’s vision while also walking back some of the famously fiddly director’s subsequent tweaks. The new UHD master, presented in HDR and Dolby Vision, was “created from the 35mm color reversal intermediate,” according to the liner notes. But there’s more: “A 1998 35mm print provided by Paramount and a 2013 digital master, both approved by director William Friedkin, were used for color reference” – and it’s clear to me the new master leans more to the former than the latter, keeping the organically filmic texture of the print rather than the cleaner look of the restoration.

Criterion’s team also avoided pushing the image into darker territory than it warrants; the HDR grade is very, very subtle, the better to preserve the naturalistic palette created by DPs John M. Stephens and Dick Bush. The one thing that stands out now is the optical downpour added over a few key scenes which were clearly shot without any rain; the quality of the shots drops just enough for the eye to detect the effect.

The original Dolby Stereo soundtrack is restored here, along with the Friedkin-approved 5.1 remix that accompanied the movie into theaters, and on Blu-ray, in 2014. For the first time on any home-video format, you can finally see Sorcerer in a version that looks and sounds like the theatrical presentation, and that’s wonderful.

The feature film goes solo on both 4K and Blu-ray platters, for maximum bitrate, with all the extras on a second BD. It’s an excellent selection, starting with Francesco Zippel’s feature-length 2018 documentary Friedkin Uncut – which features Sorcerer screenwriter Walon Green among its all-star cast of talking heads, along with Friedkin’s collaborators Ellen Burstyn and William Petersen and professional pals Dario Argento, Francis Ford Coppola, Walter Hill and Quentin Tarantino.

Green and editor Bud Smith are also heard from in a collection of audio interviews conducted by author and programmer Guilia D’Agnolo Vallan for her 2003 book on Friedkin, and Hurricane Billy himself discusses the film with Nicolas Winding Refn in a wide-ranging conversation that previously appeared on the French and British Blu-ray releases of the restoration. From the production archives, we get a silent assembly of on-set footage and the theatrical trailer, which so vibrates with raw-nerve energy that I can sort of see how audiences might have been reluctant to sign up for a two-hour version.

There’s only one new supplement, but it’s a good one: A half-hour sit-down between The Ringer’s Sean Fennessey and writer-director James Gray, whose excellent and similarly overlooked The Lost City of Z has an auteurist kinship with the horror and wonder of Friedkin’s movie. As with Arrow’s 4K edition of Cruising earlier this year, this is an exceptional, essential release; it’s a shame it couldn’t have been produced while Friedkin was still around to enjoy his flowers, but if it had, he would have screwed with it. He couldn’t do it any other way.

Speaking of lost films and monomaniacs, Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould has had a similarly strange journey over the decades.

Co-written by Don McKellar and starring Colm Feore as various versions of the legendary Toronto pianist – and still, to my knowledge, the only Canadian feature film to inspire an episode of The Simpsons – François Girard’s adventurous, experimental biopic has bobbed in and out of availability since its release in 1993.

Part of the problem was Sony Classical, which snapped up the American home-video rights, didn’t know how to market it beyond their ultra-specialized audience; their giant-clamshell VHS release looked like a concert recording, and the DVD that eventually arrived from Columbia TriStar was bare-bones and barely acknowledged.

And don’t look homeward for help. Alliance Releasing’s acquisition by Entertainment One in the early 2010s plunged the film into limbo along with hundreds of other homegrown productions, only a handful of which have made it back into the world. So when Criterion manages to rescue one of these titles – as they did with Atom Egoyan’s Exotica in the fall of 2022 – it’s cause for celebration.

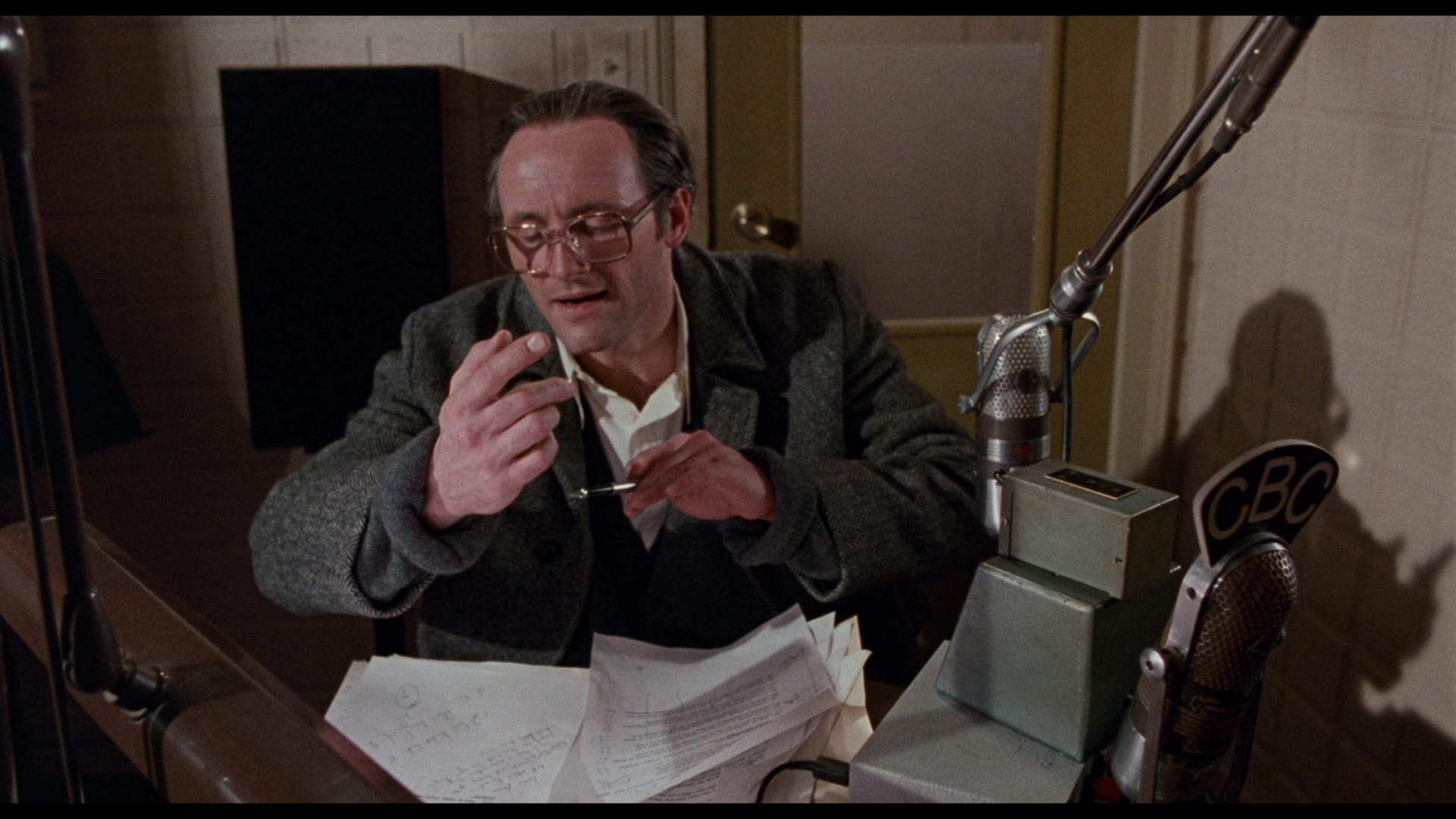

The irony is not lost on me that Criterion is releasing Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould thirty-two years after its 1993 premiere; the number has taken on a sacred standing, representing the age at which Gould chose to retire from public performance, retreating into the studio to better focus his energies and eccentricities. It is remarkable, revisiting the film now, to realize that in their fractured, experimental approach Girard and McKellar made a thoughtful and empathetic study of neurodivergence decades before the term was popularized. Thirty Two Short Films presents Gould in facets, as an eccentric, a genius, a recluse, an historian, a depressive, a comic and an addict, among other things. The compartmentalization of Feore’s performance in slivers makes it possible to see and empathize with the man in full. It’s one of the greatest performances in a career of great performances – and at a time when most people know this guy as the heavy in The Chronicles of Riddick, it is a public service to put this movie back into the world.

Criterion’s new 4K special edition – I’m so glad they didn’t restrict this one to Blu-ray – might be the best that Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould has ever looked. Where the 35mm prints had the slight blue-green tint so common to Canadian film processing labs at the time, this new restoration, supervised and approved by Girard, lets Alain Dostie’s Genie-winning cinematography be seen as they clearly intended, with brighter whites and a richer range of colors. It’s not an alteration of the film’s look, but the color-correction job it’s been waiting for all along. The soundtrack is spiffed up in the same way, in a 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio that seems very faithful to the theatrical Dolby Stereo mix, but just a little more precise. Gould would surely approve.

Extras are excellent, anchored by a new audio commentary by Girard and McKellar – who still have a lot of love for this one, and rightly so – and a conversation between Girard and Egoyan, with Egoyan fulfilling the same role Sarah Polley played for him in the Exotica supplements, a colleague and contemporary still quietly awed by the artistry involved in a project he knows inside and out.

Archival extras include EPK interviews with Feore and producer Niv Fichman, whose Rhombus Media remains dedicated to finding the sweet spot between cinema and the performing arts, and Glenn Gould: On the Record and Glenn Gould: Off the Record, two companion documentaries directed by Roman Koitor and Wolf Koenig for the National Film Board’s Candid Eye series in 1959. (You can find them both here, but they look a lot better on the disc.) There’s also a theatrical trailer that tries to package the film as a quirky indie – which it is, I suppose but not like that.

So, yeah. More stuff to buy. At least you can get them cheap: Barnes & Noble’s semi-annual 50% Criterion sale kicked off last week, and Canadians save 35% off in Unobstructed View’s domestic sale. Totally worth it.

Up next: Drop is here to lock you in a restaurant with your worst fears, and I still have Arrow’s special editions of Dark City and Swordfish to talk about. Happy Canada Day, everybody!