You and Me Against the World

In which Norm spins up Criterion's new 4K editions of CARNAL KNOWLEDGE and YOU CAN COUNT ON ME. Both classics, in very different ways.

Which is worse? To talk all the time and never say anything meaningful, or to carry so much that you’re barely able to speak?

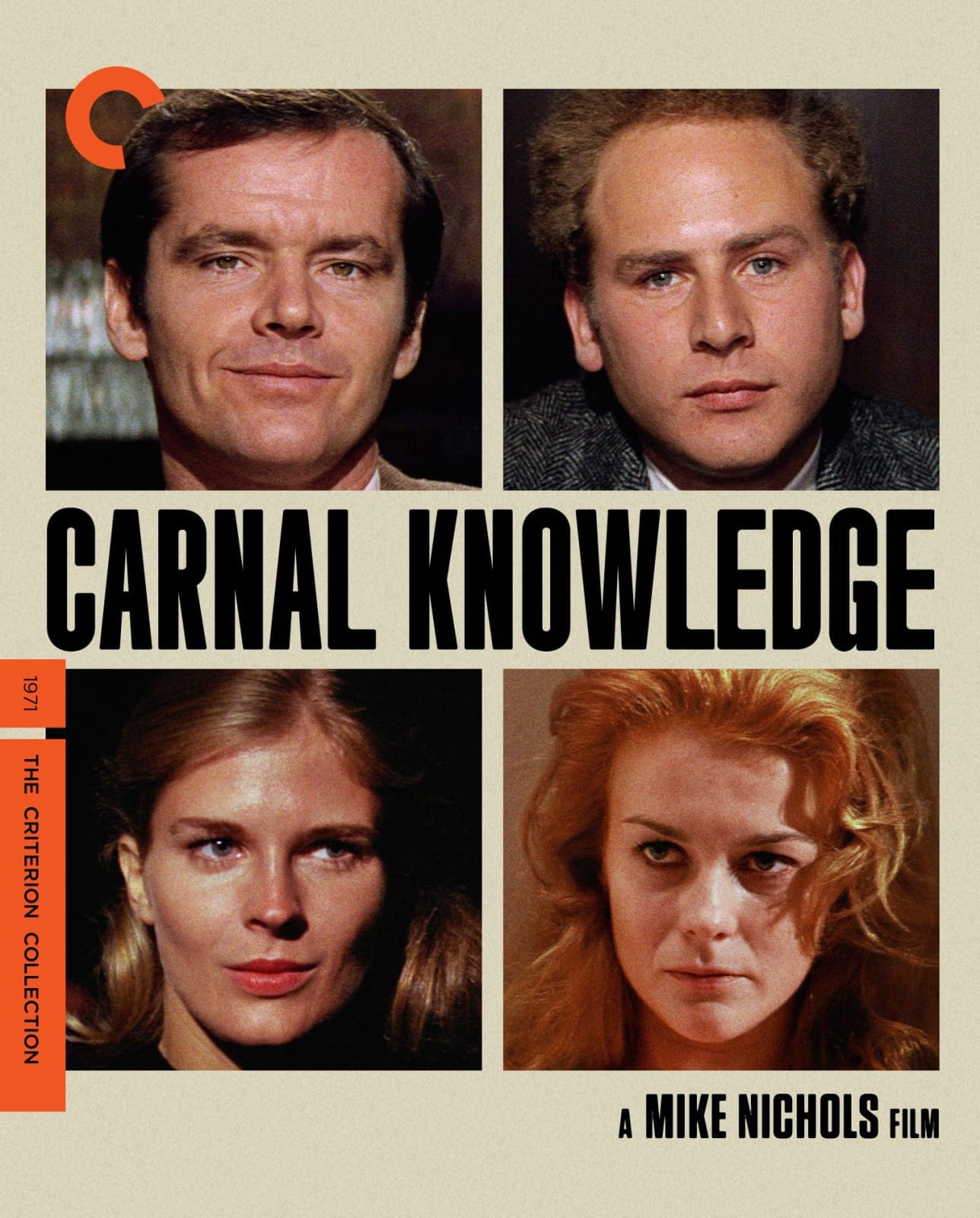

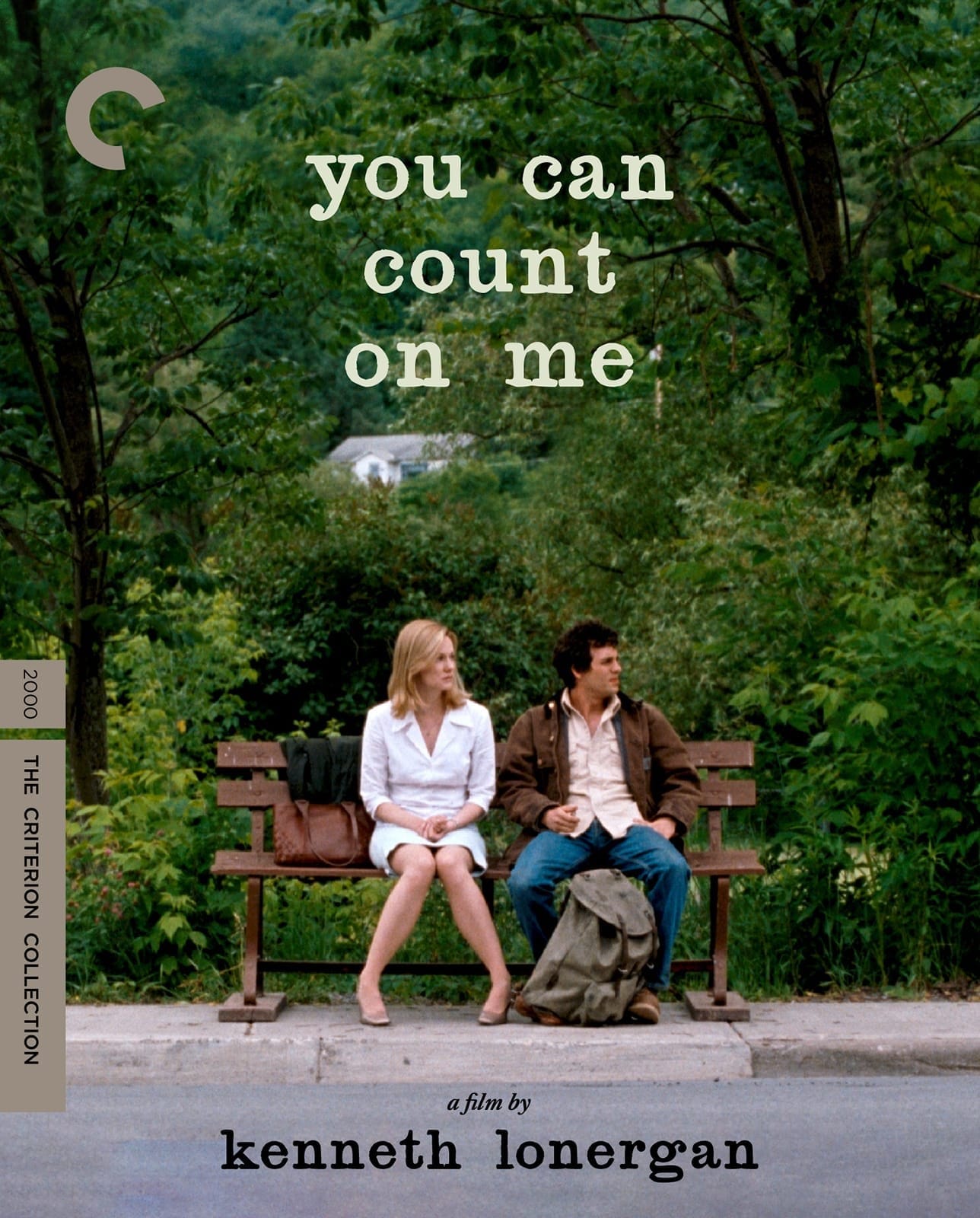

Mike Nichols’ Carnal Knowledge examined the former state in 1971; Kenneth Longergan’s You Can Count on Me, in 2000, the latter. And in a perversely perfect scheduling move, the Criterion Collection rolled both films out on disc last week in excellent special editions.

Carnal Knowledge had been released in the Collection before – on LaserDisc. There were no special features beyond a music and effects track, but it was the first time Giuseppe Rotunno’s beautiful scope cinematography was faithfully presented on home-video after a decade of truly horrible pan-and-scan transfers; in 1991, that was enough. Now it’s back, in a near-pristine 4K restoration, loaded with special features … but the movie itself is still the star. In its day, its explicit language and flashes of nudity shocked audiences still grappling with the relaxed standards that followed the death of the Hays code; now, what’s truly shocking is its unflinching honesty.

Jules Feiffer’s script follows two men, self-aggrandizing Jonathan (Jack Nicholson) and quieter, agreeable Sandy (Art Garfunkel) through a couple of decades of their friendship, opening with the two of them as college roommates in the late ’40s or early ’50s and ending in the present on what might be the last day of their acquaintance, with Jonathan freshly 40 and Sandy seeing him clearly for the first time. We see Jonathan clearly from the start: A whiny, needy, arrogant child constantly asserting a wisdom he doesn’t actually possess. The first words out of his mouth – coming out of a black screen in Nicholson’s sly, purring delivery – are a shopping list of qualities a woman must possess in order for him to want her, with the occasional pause for Sandy to agree with him. Jonathan never stops talking, not really, and he’s always talking about the same thing, which is whatever it is that he wants.

Sandy, by contrast, is quiet. Reserved. But he absorbs Jonathan’s declarations like a sponge, quickly becoming as pushy and entitled as his roommate … though he expresses this in a much whinier way. Their contrasting, codependent personalities will lay waste to a series of women, starting with the smart, composed Susan (Candice Bergen), and including but not limited to the vivacious, depressive Bobbie (Ann-Margret), the more stable Cindy (Cynthia O’Neal) and two more women, older Louise (Rita Moreno) and younger Jennifer (Carol Kane), who know exactly what’s going on.

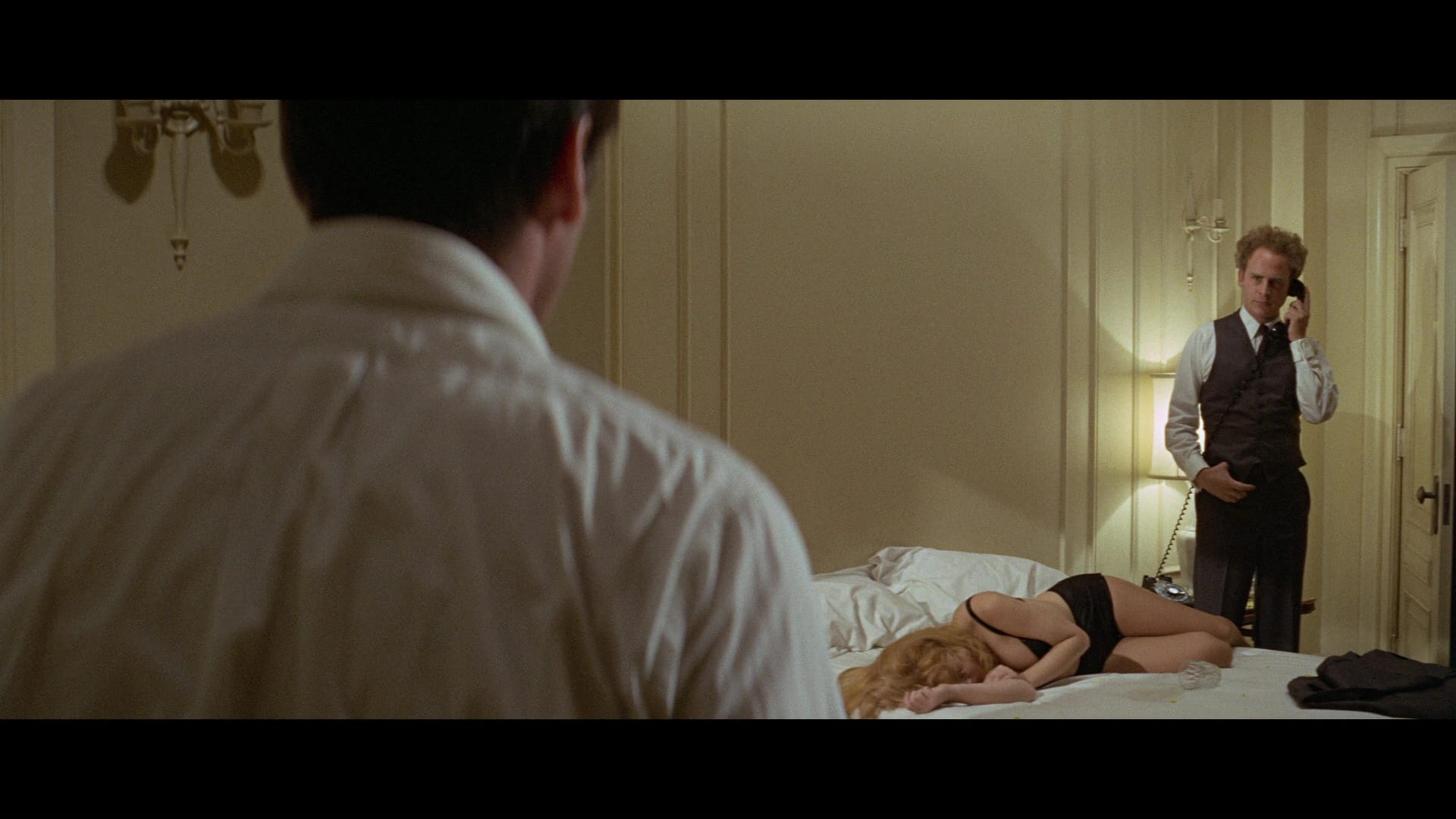

Feiffer wrote Carnal Knowledge for the stage, but Nichols never treats it like a play; he shifts fluidly from one location to another, shooting scenes in cars and forests and dorm rooms and apartments with equal verve, using the scope frame to isolate his characters with each other, or with themselves. Having made his directorial debut with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, he knows how to open up a conversation while retaining the intimacy of the performances – and their power. Carnal Knowledge gives us peak Nicholson, fresh off Five Easy Pieces and utterly unconcerned with whether audiences would find him sympathetic; hell, Jonathan’s default position of indignant self-righteousness gives Nicholson the chance to mine entire strata of selfishness and malevolence in the man’s ego.

As Sandy, Garfunkel offers a minor-key variation on that theme, wheedling Susan into a physical relationship she clearly doesn’t want – and not just because since she’s already secretly sleeping with Jonathan – and mutely enabling Jonathan for decades in all the awful shit he does. It’s curious that Feiffer’s script spends more and more time with Jonathan as time passes, with Sandy showing up for the occasional visit; maybe we’re supposed to infer that Sandy is having a more fulfilling life by comparison, but I suspect the point is Sandy wants to think that. But he keeps bringing new women to meet Jonathan, and as Jonathan monologues while Sandy nods, we can see the same questions forming in their eyes: Why are you still hanging out with this person? What do you get from each other?

Thirty years later, Kenneth Lonergan would build You Can Count on Me on the same questions … though in that case, the answers are evident to everyone. Lonergan’s protagonists, Sammy and Terry Prescott, are adult siblings who are, in every way that matters, the same broken children they were when they lost their parents.

Terry (Mark Ruffalo) is a fuckup, full stop, coming back to town to borrow money to fund his girlfriend’s abortion. Sammy (Laura Linney) is a little more settled, with a job and an eight-year-old kid, Rudy (Rory Culkin), who isn’t neglected, exactly, but demands more than she has time to give. Starting an affair with her boss (Matthew Broderick) is just the latest indication that she’s not nearly as stable as she pretends. Sammy and Terry love each other ferociously, and it’s clear they’re at their best when they’re together. But it’s also clear they both need to grow up, and Lonergan’s film is all about the tiny steps they may or may not take in that direction.

You Can Count on Me is an infinitely patient drama, noting all the ways in which Terry and Sammy fail themselves, but never each other. The title phrase is never spoken in the movie, but the siblings carry it with them like a blood oath; the one-act play from which Lonergan developed the script is included in the booklet, and it’s held back there as well. It’s a way to suggest all the other things that Terry and Sammy won’t talk about, and to fill in the blanks of their teenage years. But they also don’t talk about how much they love each other, how just knowing the other person is nearby makes them lighter. We see it in the way the volatile Terry relaxes around Sammy – he’s good with Rudy, too, but he’s still cautious. And we see it in the way Sammy becomes more centered and watchful in Terry’s presence; she’s almost a better mother to him than she is to Rudy.

Linney had been making movies for almost a decade by the time Lonergan cast her as Sammy, so she didn’t get quite as much attention as Ruffalo did. This wasn’t Ruffalo’s first film, but it might as well have been; he was a revelation as the bruised, sweet-faced Terry, ragged and alive, with a distinct sexual charge to his quiet sadness that led more than a few critics to invoke the young Marlon Brando. I didn’t see it then, but I see it now – there’s something Ruffalo does with his eyes here, avoiding everyone’s gaze out of either shyness or shame, that recalls Brando in On the Waterfront.

But where Brando could dull down his intelligence to play a bum like Terry Malloy, Ruffalo can’t hide his sharper edges; it gives Terry Prescott the weight of unfulfilled potential, of a different sort of failure. He also could have been a contender. He might still be, if he can find his way back to himself. Maybe Sammy can too.

Another contrast in these two films, and a telling one: While Nichols and Feiffer make their contempt for their protagonists clear by the end of Carnal Knowledge – and maybe far earlier than that – Lonergan is equally clear that You Can Count on Me holds no animosity towards the Prescotts. He’s rooting for these people to be their best selves, or at least start working towards being them. Lonergan’s earlier stage plays, like This Is Our Youth, were a little more ambivalent, leaving space for the audience to decide where to put their sympathies, but once he started making movies he became a lot more optimistic. The protagonists of Margaret and Manchester By the Sea may be harder to connect with, but they’re no less deserving of empathy than Terry and Sammy.

Rebecca Gilman makes a similar point in her booklet essay, which turns out to be an illuminating and essential element of an expertly curated package. Incredibly, Paramount never released You Can Count on Me on anything other than DVD; this is its first high-definition release ever, and the new 4K master is a thing of beauty. The subtle tones and naturally lit exteriors of Stephen Kazmierski’s cinematography are rendered here exactly as they appeared in the 35mm prints, with an HDR grade that’s almost invisible. (The sun feels warmer in a few key scenes, is all, and even that difference might be the result of the circumstances in which I originally saw the movie.) Audio is the same unobtrusive DTS-HD 5.1 mix as it was in theaters, the front-forward soundstage keeping the dialogue clear and letting Lesley Barber’s score and a carefully chosen soundtrack fill the rest of the space as needed.

Extras are modest but excellent: Lonergan’s audio commentary from the 2001 DVD release is here (though Paramount’s generic “A Look Inside” featurette didn’t make the cut), and it gets new context with a pair of new retrospective interview featurettes. Lonergan gets the spotlight in a half-hour sit-down that lets him discuss his career path and the choices that led to the film as it is. (He worried that he was too familiar with Ruffalo, whom he’d directed in This Is Our Youth, so he originally offered the role of Terry to Ethan Hawke – who never read the script.) And Ruffalo, Linney and Broderick all contribute to a second half-hour piece, “An Area We Ought to Explore,” reminiscing about the shoot in general and their performances in particular. It’s clear that every one of these people loves the thing they made, and the work they put into it, and the quarter-century that’s passed has only made that affection stronger. I can see why.

Carnal Knowledge’s special features are more forensic: The writer and director are dead, and none of the cast is here either. (I found myself wondering if one or two of them might have been available, but Criterion’s producers didn’t want to present an unbalanced view of the film.) Nichols is represented in a 2011 Q&A with Jason Reitman, recorded after a screening at Lincoln Center, and Feiffer appears via a 2019 episode of the To Live and Dialogue in LA podcast taped in post-screening conversation with host Aaron Tracy.

Further context is provided by experts: There’s a new audio commentary from Neil Labute, whose Your Friends and Neighbors offered a similarly venomous look at assholes and their acolyte; a conversation about the film between Nichols’ biographer Mark Harris and critic Dana Stevens and a segment in which film-editing historian Bobbie O’Steen discusses her late husband Sam’s work on the film. It’s all worth watching, though the moments in which Feiffer and Nichols discuss the controversies around the movie, and the way audiences responded to such a confrontational work, is easily the most essential … and the most telling. The movie hasn’t changed, after all. I’m not sure we have either.

Carnal Knowledge and You Can Count on Me are now available in the Criterion Collection in 4K/Blu-ray combo and BD-only editions.

Up next: The Legend of Ochi and Small Soldiers offer an interesting conversation about kids and their practical pals. And don't forget, readers on the paid tier get my weekly What to Watch recommendations every Friday! Upgrade your subscription so you don't miss anything!