Anyway, They Delivered the Bomb

In which Norm beholds Christopher Nolan's OPPENHEIMER.

Happy Thanksgiving, American readers! Or happy Black Friday, I guess, and I hope your shopping was ethical. Also, I hope you bought a lot of discs at rock-bottom prices. One of them was probably Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, right? Because, having finally caught up to it this week, it is glorious.

In terms of the experience, anyway; it is, like most of Nolan’s work, an unimpeachable technical accomplishment that’s just a little cold around the heart.

It must have been spectacular in IMAX, and once again I regret that my July did not allow for me to sneak off for three hours and see this film as its creator clearly means it to be seen; the famously gearheaded Nolan has long championed celluloid, and large-format celluloid at that, as the best way to experience his work, and he recently stated that the home version of Oppenheimer is his best possible approximation of the theatrical presentation – but only an approximation. So I watched it in 4K, projected on a 100” screen, with the 5.1 soundtrack firing in DTS-MA as dictated. And it might not have been IMAX 70mm, but it looked and sounded pretty damn great.

If you’re chasing the high of a singular audiovisual experience, Oppenheimer delivers. Nolan infuses a bottled Great Man biographical drama (adapted from Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin's 2005 book American Prometheus) with the scrambled, anxious neurosis of a protagonist desperately trying to deny that his theoretical research is not theoretical in the slightest: He’s been tasked to perfect the atomic bomb before the Nazis do, and success means the deaths of thousands upon thousands of human beings.

Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema lock us into the headspace of their subject, embodied by Cillian Murphy as a man pre-emptively withered by the karma he’s creating. Or maybe his hollowed look – a literal scarecrow, which may itself be Nolan’s own in-joke – is meant to suggest the radiation poisoning he’s about to inflict on the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

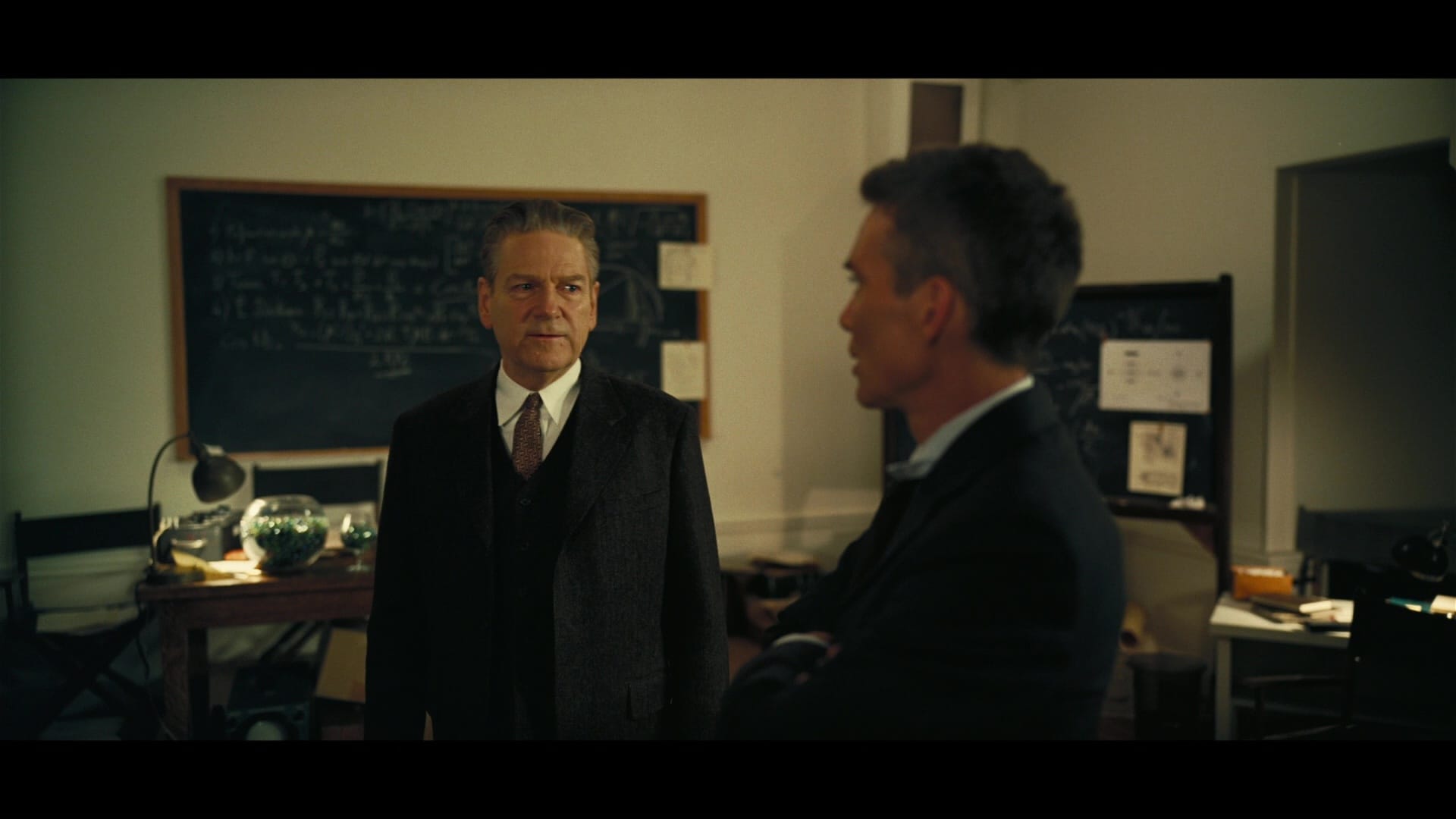

Whatever you decide it means, Murphy’s is a very good performance; he carries the film’s stress on his shoulders, remaining still and calm as everyone around him loses their goddamn minds over this setback or that betrayal. If this is a heist picture, Matt Damon’s General Groves is the money guy, cranking about how much everything will cost while still signing every check; Kenneth Branagh’s Niels Bohr is the Michael Caine mentor/fixer, turning up to admire our hero’s skills and provide reassurance that he’s on the right path.

David Krumholtz, styled after Alfred Molina, turns Oppy’s old pal Isidor Rabi into the fussy sidekick who nopes out of the scheme once he realizes its danger. And Benny Safdie’s Edward Teller is the fretter who sticks around, worrying everything will fall apart – only here, the stakes are nothing less than the end of the world, as his science has led him to conclude Oppenheimer’s “gadget” has a non-zero chance of igniting the atmosphere and incinerating the planet on its first test.

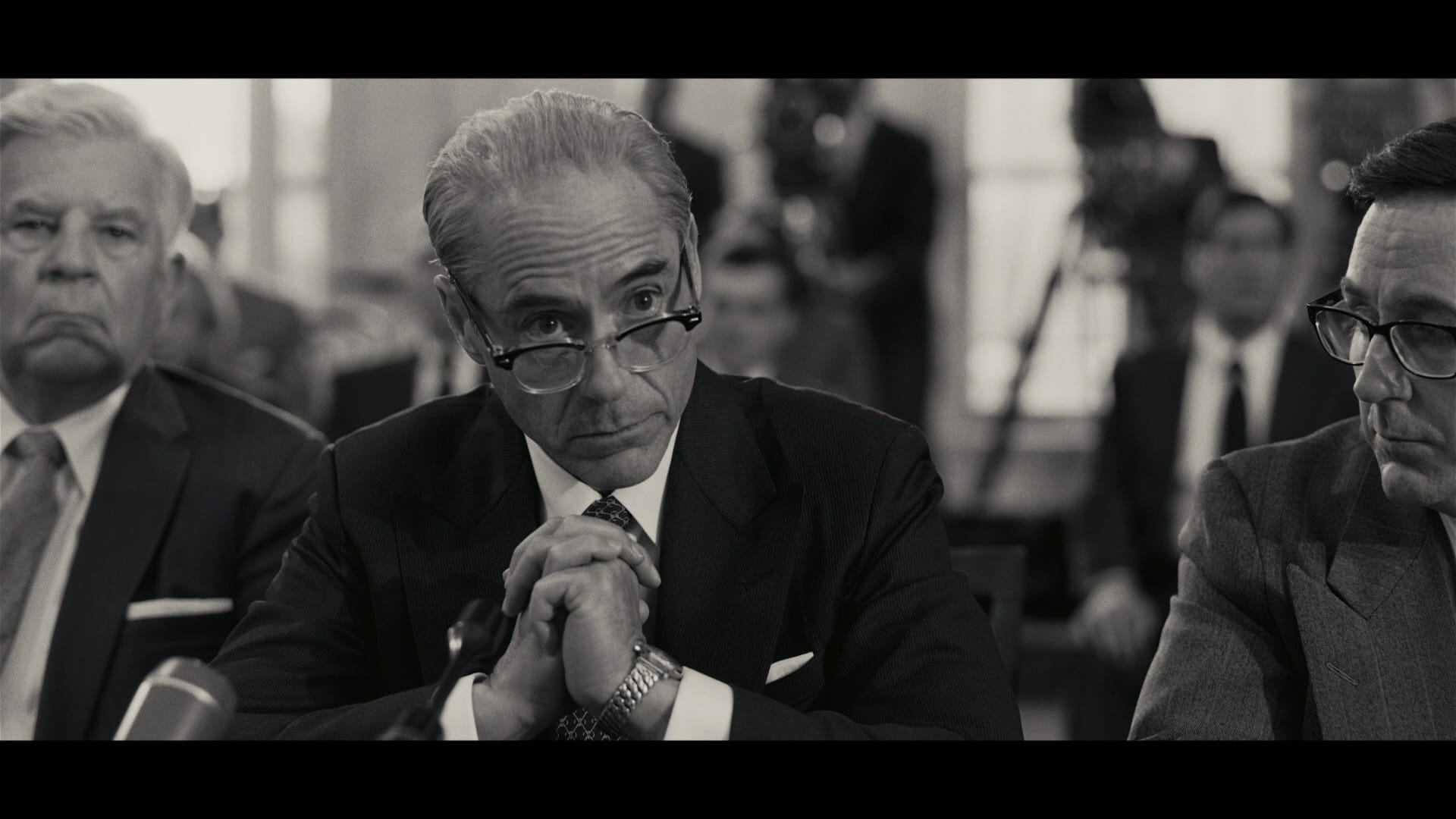

There’s also a framing sequence built around a 1954 hearing over Oppenheimer’s security clearance that’s tied to the Senate confirmation of Lewis Strauss as Eisenhower’s Secretary of Commerce five years later. It’s a lot, setting the stakes in the “J. Robert Oppenheimer has to think about his whole life before he goes onstage” mode, but it also gives us Robert Downey Jr. as a particularly pissy Strauss, the closest thing Nolan offers to a villain beyond the Axis powers. (Fun fact: Inception, Nolan’s actual heist movie, doesn’t really have a villain either.)

Having revisited Roland Joffé’s 1990 Manhattan Project drama Fat Man and Little Boy earlier this year in Impact’s Directed by Roland Joffé set, I was curious to see how Nolan would handle the lack of tension inherent in a narrative where the ending is known to literally everyone who’s bought a ticket. Joffé and co-writer Bruce Robinson structured their version as a series of squabbles between Paul Newman’s bulldog Groves and Dwight Schultz’ anxious Oppenheimer, dangling the horror of the bomb through two fictional characters, a researcher and nurse played by John Cusack and Laura Dern, whose romance is derailed by his horrific death by radiation poisoning.

Nolan’s not interested in that sort of drama, even dialing down the legitimate sources available to him in the historical record – the relationship between Oppenheimer and Groves is never less than professional, with Damon playing the character as impatient but respectful of the eggheads in his charge, and while both Emily Blunt and Florence Pugh discuss the dimensionality of their characters in a documentary elsewhere on the disc – both Kitty Oppenheimer and Jean Tatlock were brilliant women constrained by the gender roles of the era – any chance the actors might have had to express that dimensionality is smothered by the script’s single-minded focus on Oppenheimer.

In that same documentary, Nolan talks about assembling his massive supporting cast by focusing on distinctive actors the audiences could connect to, freeing him from worrying about making sure we could keep a dozen physicists and another dozen government functionaries straight in our heads. It’s an excellent strategy, providing you’re Christopher Nolan; other directors who don’t have the budget or the reputation might struggle to land Tony Goldwyn for Tribunal Member #2 or Tom Conti to play Albert Einstein. Hell, most directors wouldn’t be able to get a movie with this many speaking parts greenlit in the first place.

And that might be the problem with Oppenheimer as a movie; it wouldn’t exist if Christopher Nolan hadn’t wanted to make it, but it’s also a movie made by someone with the juice to do whatever he wants, with no oversight or questioning of his choices, as long as his name on the marquee guarantees a blockbuster. But some questions might have helped sharpen the picture into something truly worthy of his ambition.

Is the delicacy with which the film treats Oppenheimer’s infidelities another aspect of the ends justifying the means – the movie arguing that he had to sleep around in order to be his best self – or just another signifier of Nolan’s blind spot for female characters? I’m similarly uncertain that the film’s denouement needs to be half an hour long, as Nolan expands the framing sequence into a subplot about espionage, Communism and the personal grievances of Downey’s Strauss, all designed to give Oppenheimer a morally uncomplicated victory and send the audience out of the theater on a high. Which … sure? But given the whole “invented the atomic bomb” thing, I think I’d have preferred a little ambiguity.

Universal’s 4K edition of Oppenheimer is a three-disc set, with the feature sitting alone on the UHD platter for maximum bitrate; there’s also an excellent 1080p version on its own Blu-ray disc. But the 4K version is a knockout, its HDR grade bringing out both the eerie blue of Murphy’s eyes and a host of deeper reds and oranges in the Los Alamos landscape – to say nothing of the overwhelming yellows and whites of the climactic bomb detonation. The sound mix is just as detailed, even if it’s not in Atmos.

A second Blu-ray holds a suite of handsomely produced supplements, starting with “The Story of Our Time”, a stately look at the production that runs 72 minutes and offers cast-and-crew interviews that push beyond the standard pleasantries, and Christopher Cassel’s thoughtful feature doc To End All War: Oppenheimer & the Atomic Bomb, produced for MSNBC to draft on the release Nolan’s film and featuring interviews with Oppenheimer’s grandson Charles, Hiroshima survivor Hideko Tamura and scientists Bill Nye and Michio Kaku, among others.

There’s also a post-screening panel discussion with Nolan, Bird and physicists Thom Mason, Carlo Rovelli and Kip Thorne moderated by Chuck Todd for NBC’s Meet the Press (you can view it in its entirety here) and a trailer gallery that showcases the remarkable control Nolan brought to marketing the picture, starting with abstraction and wonder while gradually keying his audience to understand it’d still move like a thriller. (Consider the way in which the IMAX trailer plays up the whole “ignite the atmosphere” angle, for the super-fans.)

Finally, there’s “Innovations in Film”, a little featurette – produced by Fotokem – about the unprecedented work required to shoot the 65mm black-and-white sequences, which started with Kodak reconfiguring its film processing facility to accommodate the tanks required because Nolan didn’t want to shoot on color stock. One can appreciate the achievement while also noting that none of the effort was actually necessary, as even in IMAX audiences would never have known the monochrome footage wasn’t shot on B&W stock – but that’s monomania for you, I guess. Or maybe Nolan’s dedication to keeping photochemical film alive really does require this level of commitment, as long as a studio is willing to pay for it. As fixations go, it’s a benevolent one.

Oppenheimer is available in 4K and Blu-ray combo editions from Universal Studios Home Entertainment. And congrats to Kevin Ahoy, Paul Murphy and Shaun Sayer, winners of their very own 4K combos! Your discs are on the way.

In this weekend’s paid edition: Criterion launches a new art-house imprint, and brings a ’90s thriller back to life. Don’t miss out! Update that subscription if you haven’t already! And if you haven’t already, what are you waiting for?